Just Beginning – Donor Profiles: World Bank and UNICEF

Reports

Below are two donor profiles compiled to support our scorecard Just Beginning: Addressing inequality in donor funding for Early Childhood Development. This research presents an overview of the disbursements that UNICEF and the World Bank have made to Early Childhood Development (ECD) overall, and to pre-primary more specifically over the last 15 years. The research has chosen to focus on UNICEF and the World Bank given that these donors are seen to have led global efforts in promoting arguments in favour of investing in children in the early years, as laid out in their planning documents. The strategies outlining commitments over the SDG period of both donors illustrate the emphasis they place on investing in pre-primary education, recognising that without investment here targets for other SDG areas are unlikely to be met. UNICEF and the World Bank are the largest multilateral donors to ECD in 2016. In addition, the World Bank continues to be the largest donor to pre-primary education in volume terms, while UNICEF is amongst the largest in terms of its share of the total ODA to pre-primary education. Yet, as the following profiles illustrate, financial commitments to pre-primary education by both these donors highlights that, even with these donors, their stated commitment to pre-primary education is not sufficiently matched by their spending

Just Beginning Ecd Donor Profiles Online

This research presents an overview of the disbursements that UNICEF and the World Bank have made to Early Childhood Development (ECD) overall, and to pre-primary more specifically over the last 15 years. The research has chosen to focus on UNICEF and the World Bank given that these donors are seen to have led global efforts in promoting arguments in favour of investing in children in the early years, as laid out in their planning documents. The strategies outlining commitments over the SDG period of both donors illustrate the emphasis they place on investing in pre-primary education, recognising that without investment here targets for other SDG areas are unlikely to be met.

UNICEF and the World Bank are the largest multilateral donors to ECD in 2016. In addition, the World Bank continues to be the largest donor to pre-primary education in volume terms, while UNICEF is amongst the largest in terms of its share of the total ODA to pre-primary education.

Yet, as the following profiles illustrate, financial commitments to pre-primary education by both these donors highlights that, even with these donors, their stated commitment to pre-primary education is not sufficiently matched by their spending

World Bank

The World Bank’s ECD Strategy

The World Bank defines its ECD strategy as being targeted towards the growth and development beginning from the moment a child is conceived up until the child is 83 months of age (or near the age of entry to attend primary school).

Based on this definition, a World Bank review of its investments in ECD between 2001 to 2013 indicate that it had invested US$3.3 billion in support of 116 ECD projects. These were within three areas of (1) Education, (2) Health, Nutrition and Population and (3) Social Protection and Labour.

The cost effectiveness of interventions towards ECD have meant a policy shift in recent years towards prioritising ECD by the World Bank.

The World Bank takes the view that “ECD is one of the smartest investments a country can make in its future…..[and] if a child gets the health care, nutrition, affection, simulation, and education that she needs – the gains she makes in those early years are hers for life” (Hansen, 2016).

Based on the growing evidence base supporting the benefits of investing in young children, the World Bank’s website indicates that the World Bank Group is “increasing its support of early childhood initiatives around the world through financing, policy advice, technical support, and partnership activities at the country, regional and global levels” (Sayre et al., 2015).

Total resources for ECD

A review by the World Bank of its ECD portfolio of projects both under International Development Association (IDA) and International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) indicates that in total over 2001-2013, US$3.3 billion was committed to ECD (Sayre et al., 2015).

Of the 116 projects the World Bank reported it was undertaking over this period, 59 were for the Health, Nutrition and Population sector which totalled US$2.2 billion (65% of the total). Education under the ECD portfolio, had 42 projects, with commitments totalling US$925 million (28% of the total) (Sayre et al., 2015).

Comparing geographic regions prioritised by the World Bank – both in terms of total commitments and total projects – the Latin America and Caribbean and Africa regions appear as the largest recipients of the World Bank’s ECD projects.

Disaggregating this between the three different World Bank sectors of ECD, Africa is by far the largest recipient region for resources for the Health, Nutrition and Population, while the Latin America and Caribbean region is the largest recipient for Education and Social Protection ECD commitments. A World Bank comparison of per capita investment on all ECD projects by country between 2001 and 2011 indicate that higher investment in children in Latin America and the Caribbean is more likely to be the case than, say, children in Africa or South Asia.

While the World Bank review focused on commitments, an analysis of disbursement data based on the assumptions used to estimate World Bank contributions to ECD (see www.theirworld.org/5for5-methodology) indicate that disbursements to ECD have increased by 1.3% every year between 2002 and 2016 reaching US$374 million in 2016.

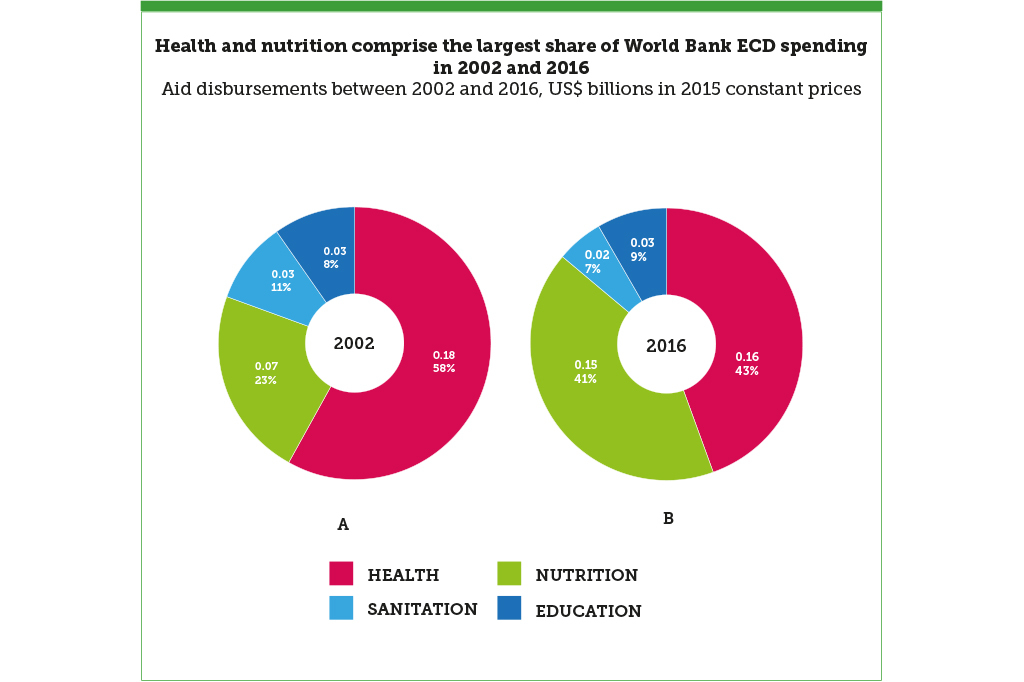

A large part of the growth in ECD has been driven by the nutrition sector which has, in real terms, grown by 5.6% per year. Disbursements to pre-primary education have risen by 2.0% in real terms every year over the 2002 to 2016 period. The ECD component for health, in comparison, has fallen slightly by 1.0% a year. In contrast, despite health remaining the largest share of the amount the World Bank disburses to ECD ODA its share has declined from 58% to 43%, largely as a consequence of a larger share being disbursed to nutrition (Figure 1A and 1B).

Spending on pre-primary education

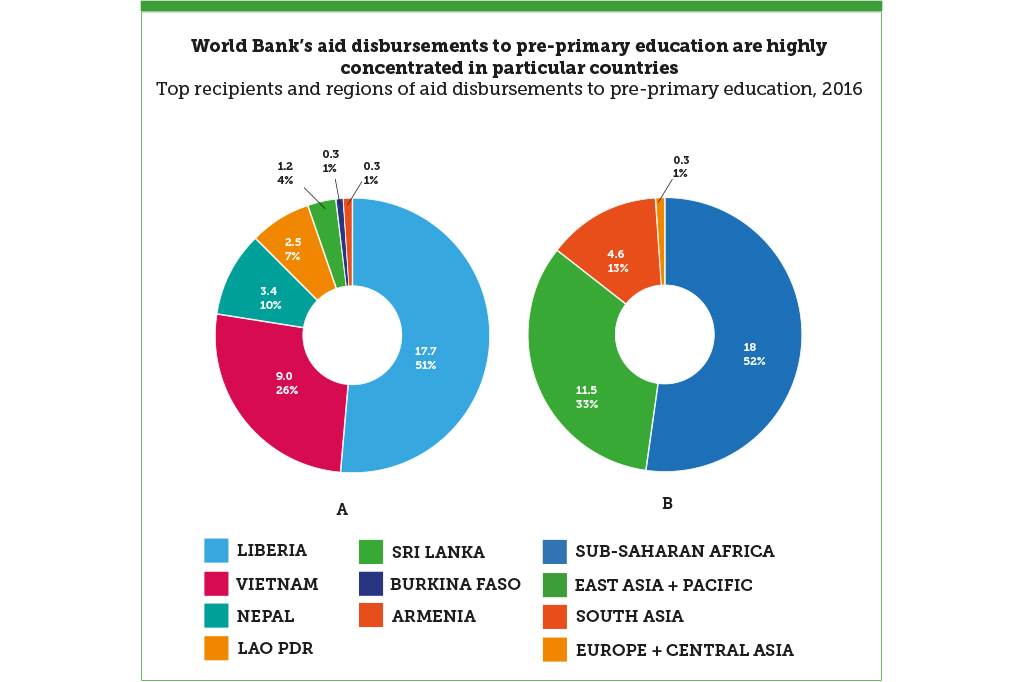

With respect to pre-primary education, the World Bank’s Education Strategy view states that “foundational skills acquired early in childhood make possible a lifetime of learning [with] the traditional view of education as starting in primary school taking up the challenge too late” (World Bank, 2011). In 2016, the World Bank disbursed US$34 million to pre-primary education. This aid is heavily concentrated and was disbursed to eight countries. Over three-quarters of pre-primary ODA went to just two recipients: Liberia (51%) and Vietnam (26%) (Figure 2A and 2B).

While the World Bank is the largest donor to pre-primary education – disbursing the equivalent of 42% of global pre-primary ODA disbursements from all donors in 2016 – as a share of total ODA that the World Bank disburses, the share going to pre-primary education is just 0.28%. While this still places the World Bank as the 6th largest donor according to prioritisation of pre-primary spending as a share of their total ODA, it is still significantly off target from the proposed Theirworld target that donors should target 15% of total ODA to education, of which 10% should be for pre-primary education.

To reach the 2030 pre-primary target set by Theirworld, the World Bank’s fair share contribution would need to reach US$459 million (or 8% of the global US$5.8 billion target). Between now and 2030, World Bank disbursements to pre-primary education would need to increase by 20% a year. Our calculations suggest that, based on current trends of World Bank disbursements to pre-primary education, the World Bank will only meet 10% of its fair share target.

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System, accessed January 2018

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System, accessed January 2018

UNICEF

UNICEF’s ECD strategy

UNICEF defines ECD as encompassing all stages which run from conception all the way to age 8; it distinguishes ECD according to three diowstinct phases namely conception to birth, birth to age 3 and pre-school years. UNICEF’s ECD framework centres around the SDGs relating to Target 2.2 (nutrition), Target 3.2 (health), Target 4.2 (education) and Target 16.2 (protection) (UNICEF, 2017a).

The key “ingredients of healthy early childhood development” identified by UNICEF are nutrition and health initiatives relating to immunisation, disease prevention and treatment, protection from toxic stress, violence, neglect and conflict and stimulation through play and quality early learning opportunities (UNICEF, 2017b).

In 2017, UNICEF reiterated the call to action that with the irrefutable benefits of ECD it must be a global and national priority for all stakeholders to achieve the ECD goals set out in the SDGs and they must “place early childhood development at the top of their economic and political agendas” (UNICEF, 2017b). Insofar as financing for ECD is concerned, UNICEF’s strategy states that governments and partners must “invest urgently in services that give young children, especially the most deprived, the best start in life [by] increasing t overall share of budgetary allocations for early childhood development…..for example, allocating 10 per cent of all national education budgets to pre-primary education” (UNICEF, 2017b).

Total resources for ECD

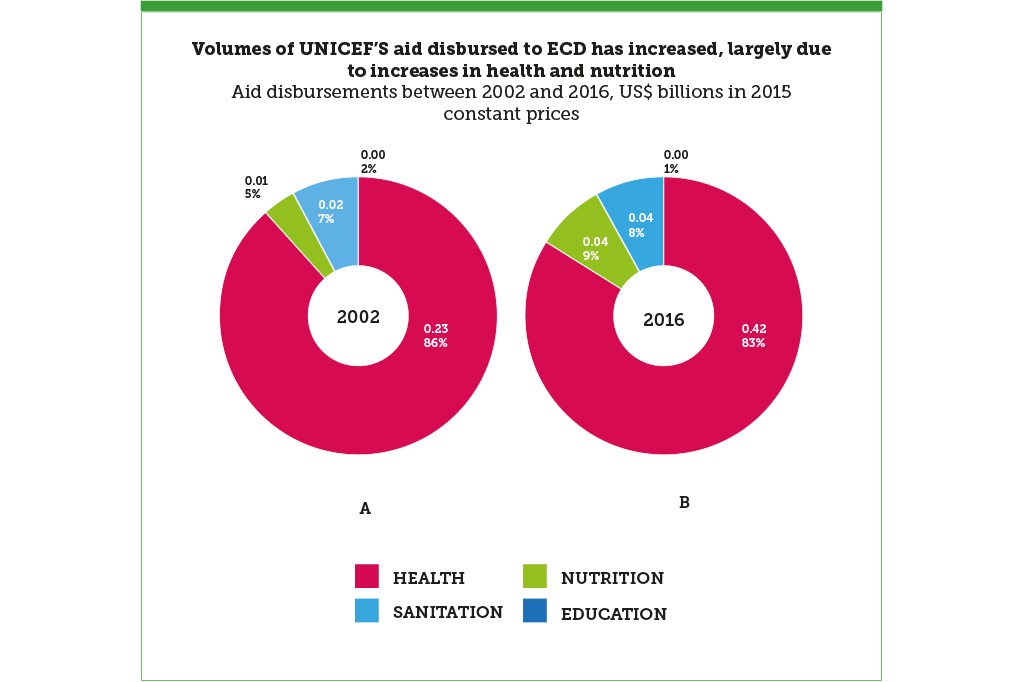

An analysis of disbursement data based on the assumptions used to estimate UNICEF’s contributions to ECD (see www.theirworld.org/5for5-methodology) indicate that disbursements to ECD have increased by 4.8% every year between 2002 and 2016 reaching US$510 million in 2016. A large part of the growth has been driven by the nutrition sector which has, in real terms, grown by 8.6% per year. Disbursements to pre-primary education, on the other hand have fallen by 0.4% in real terms every year over the 2002 to 2016 period. As a consequence the share of UNICEF’s ECD ODA going to pre-primary education has declined from 2% to 1%, while nutrition has increased from 5% to 9% (Figure 3A and 3B).

Spending on pre-primary education

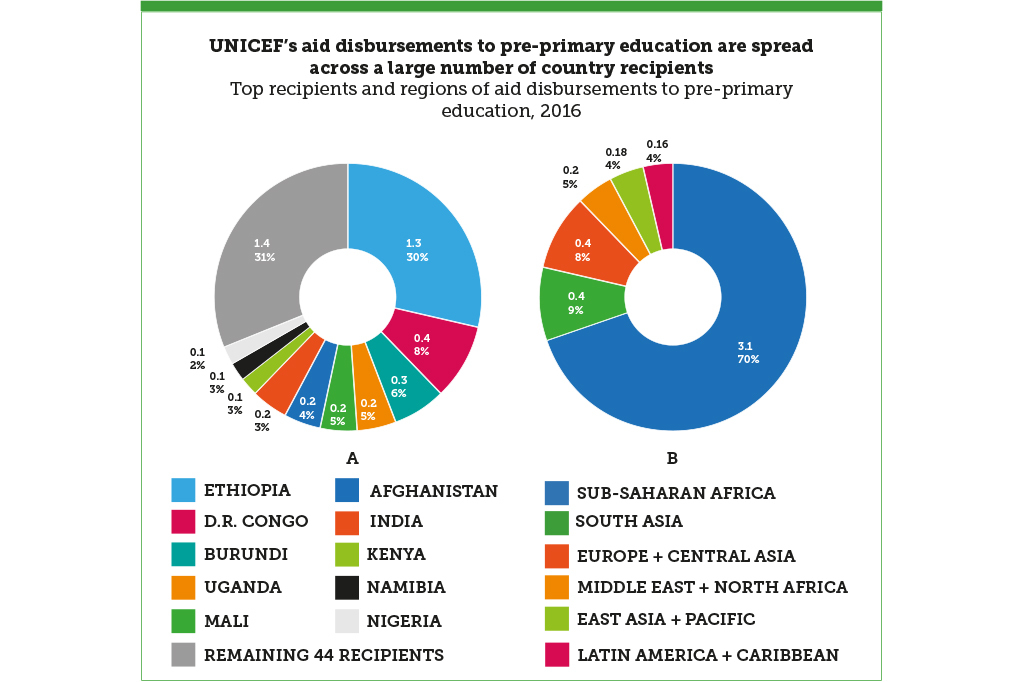

In 2016 UNICEF disbursed US$4 million to pre-primary education making it the 6th largest donor to pre-primary education in volume terms after the World Bank, Canada, Korea, United Arab Emirates and Germany. UNICEF’s disbursements, however, are spread thinly across a large number of recipients: in 2016, UNICEF disbursed pre-primary education support to 54 countries. The largest recipient, Ethiopia, received 30% of the spending. More generally, many of the top recipients of UNICEF’s pre-primary education ODA are in the sub-Saharan African region making this the largest region in receipt of disbursements (Figure 4A and 4B).

UNICEF ranked as the 4th largest donor with respect to the share of total ODA disbursed to pre-primary; in 2016 this was the equivalent of 0.31% and considerably lower than the proposed Theirworld target for pre-primary education. For the period 2002-2016, prioritisation of pre-primary education in UNICEF’s aid programming peaked over 2006-2010 before both volume and the share of total ODA going to pre-primary education declined to their lowest levels.

To reach the 2030 pre-primary target set by Theirworld, the UNICEF’s fair share contribution would need to reach US$339 million (or 6% of the global US$5.8 billion target).

Between now and 2030, UNICEF’s disbursements to pre-primary education would need to increase by 36% a year. On current trends, UNICEF’s disbursements to pre-primary education will only meet 1% of its fair share target, according to our calculations.

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System, accessed January 2018

Source: OECD Creditor Reporting System, accessed January 2018

References

Hansen, K. (2016). Early Childhood Development: A smart investment for life. World Bank, Washington D.C.

http://blogs.worldbank.org/edu…

Sayre, R., Devercelli, A., Neuman, M. and Wodon, Q. (2013). Investing in Early Childhood Development: Review of the World Bank’s recent experience. World Bank, Washington D.C.

https://openknowledge.worldban…

Spears, D. (2013). How much international variation in child health can sanitation explain? Policy Research Working Paper, Report Number WPS6351, World Bank, Washington D.C.

http://documents.worldbank.org…

UNICEF. (2012). A brief review of the social and economic

returns to investing in children. United Nations Children’s Fund, New York.

https://www.unicef.org/socialp…

UNICEF. (2017a). UNICEF’s Programme Guidance for Early Childhood Development: UNICEF Programme Division 2017. United Nations Childrens’ Fund, New York.

https://www.unicef.org/earlych…

UNICEF. (2017b). Early Moments Matter for every child.

United Nations Children’s Fund, New York.

https://www.unicef.org/publica…

UNICEF, World Health Organization and World Bank. (2017). Levels and Trends in Child Malnutriton: Joint child malnutrition estimates — Key findings of the 2017 edition. New York, Geneva, Washington.