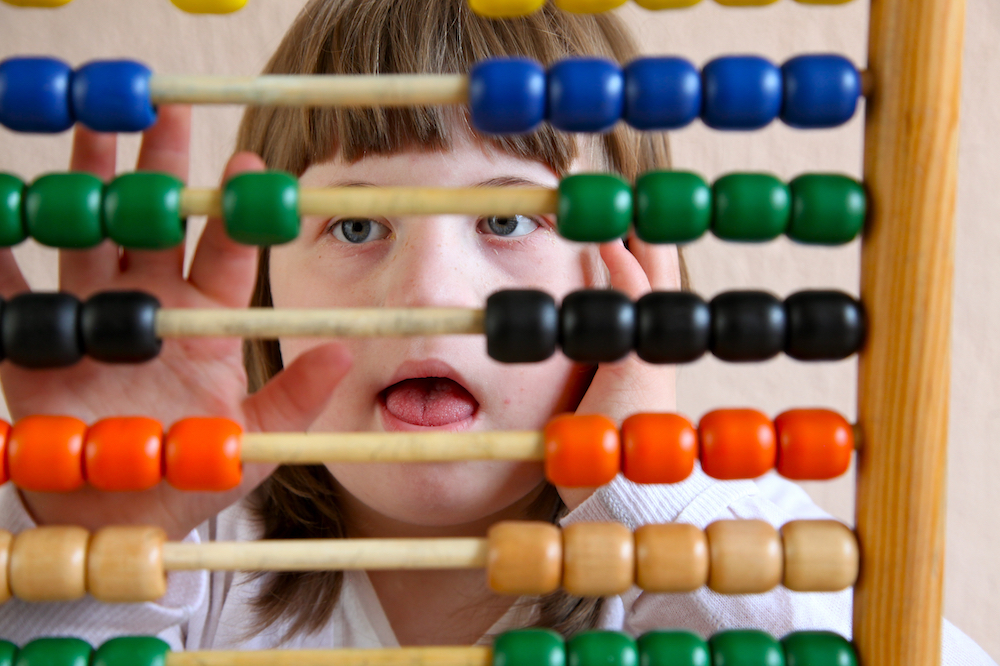

‘Disability is not inability’: breaking down stigma and helping children into school

Barriers to education, Children with disabilities, Early childhood development, Girls' education, Right to education, Teachers and learning

Helping children with disabilities to find their confidence, as well as changing attitudes and policies, are key if they are to access education and independence.

Children with disabilities are among the most vulnerable in any society. They rely even more on the love and care of their parents, family and the wider community.

When children with a physical or mental disability – or both – are born into extreme poverty, deprivation or conflict, their chances of fulfilling their potential are drastically reduced.

They can face discrimination in the form of negative attitudes, lack of adequate policies and legislation, and little or no opportunity for education.

A report on education for girls with disabilities – called Still Left Behind – was published recently by the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative and the charity Leonard Cheshire Disability.

It said disabled girls suffer double discrimination, adding: “Cultural bias and rigid gender roles are the most frequently mentioned barriers to education for girls with disabilities.”

It said there are many other barriers – such as girls with disabilities not being expected to work and therefore not needing an education. Transport, toilet facilities and the attitude of teachers are among other factors.

In many countries, disabled children are hidden away. Estimates in the World Report on Disability (2011) suggest there are between 93 million and 150 million children under 14 with disabilities in the world. But the numbers could be much higher.

Susie Bennett, head of communications for charity ADD International (Action on Disability and Development) said there are few reliable data sources.

She added: “At the heart of the work of disability activists is the drive to increase the engagement of disabled people at all levels of society – within families, schools, communities and power-holders.

“This empowerment must start as early as possible in a disabled person’s life. As disabled children emerge from isolation, grow in confidence and find their voice, it breaks down stigma and shifts people’s understanding of disability. This leads to changes in attitudes, behaviour and policy.

“The results are real independence. Children who had been considered worthless, a drain and a burden, are recognised as individuals with ability and worth.

“They are learning, evolving and growing up feeling and knowing that they are contributing to their families and community. A new story, that disability is not inability, comes to life.”

In Tanzania, the picture is one of hope – with a clear view to opening up the issue of childhood disability.

“We aim to get disabled children into school,” said Bennett. “Together with our disability activist partners, we will train 250 village leaders to go door to door to find disabled children who are often hidden away at home.

“We then work with parents to break down stigma and change attitudes, so parents see their child has the potential to learn and flourish and enrols him or her into school.

Young children are very honest when it comes to disability. It’s adults who don’t cope as well. Dr Abigael San, clinical psychologist

“We link parents to local income-generating schemes so that they can earn the money to pay for their child’s schooling.”

ADD International also engages teachers, schools and the community to create inclusive learning environments that have the required training, equipment and learning materials, as well as being physically accessible.

While there is progress in the promotion of care for children with disabilities – it is still an area that needs vast amounts of support and funding.

90% of brain development happens before the age of five.

Theirworld’s #5for5 campaign has been highlighting the need for investment in early childhood development – so that all children have access to quality care including nutrition, health, learning, play and protection.

Despite all the challenges for children living with disabilities – including stigma where disabled children are often considered weak or worthless – it’s usually not other children who are the problem.

They deal with disability very differently than many adults – it seems there is more acceptance.

Clinical psychologist Dr Abigael San, who has worked for many years in the disability sector, said: “Young children are very honest when it comes to disability.

“They will notice that someone is different but that’s it. If a child is playing with a disabled child they will notice the disability but will still engage. It’s adults who don’t cope as well.

“One of my clients, who has very shaky hands, was trying to buy something in a shop – and the child helping at the till opened the bag wide enough for her to put her purchase inside.

“Children see the disability and help. Adults are sometimes too embarrassed to.

“Plus children will just come out and ask. Like why do you have this? They question disability openly without making a judgement.”

An example of this comes from a recent UNICEF report where a four-year-old child with cerebral palsy is integrating well into a pre-school nursery in Veles, Macedonia.

“Mihail, four-year-old, has cerebral palsy,” said the report. “He is one of the few children with disabilities who attend kindergarten in the country.

“Playing games together with other children, and especially with his best friend Ljupco, is one of the things he loves most.”

Mihail’s teacher Maya said: “When included in playing games on an equal basis with other children, Mihail builds self-confidence and independence.

“Cheering makes him proud of his achievements. The same goes for all the other children.”

More news

Technology has the power to expand education for children with disabilities