Early Childhood Development Week: playing teaches children so many life skills

Childcare, Early childhood development, Safe pregnancy and birth

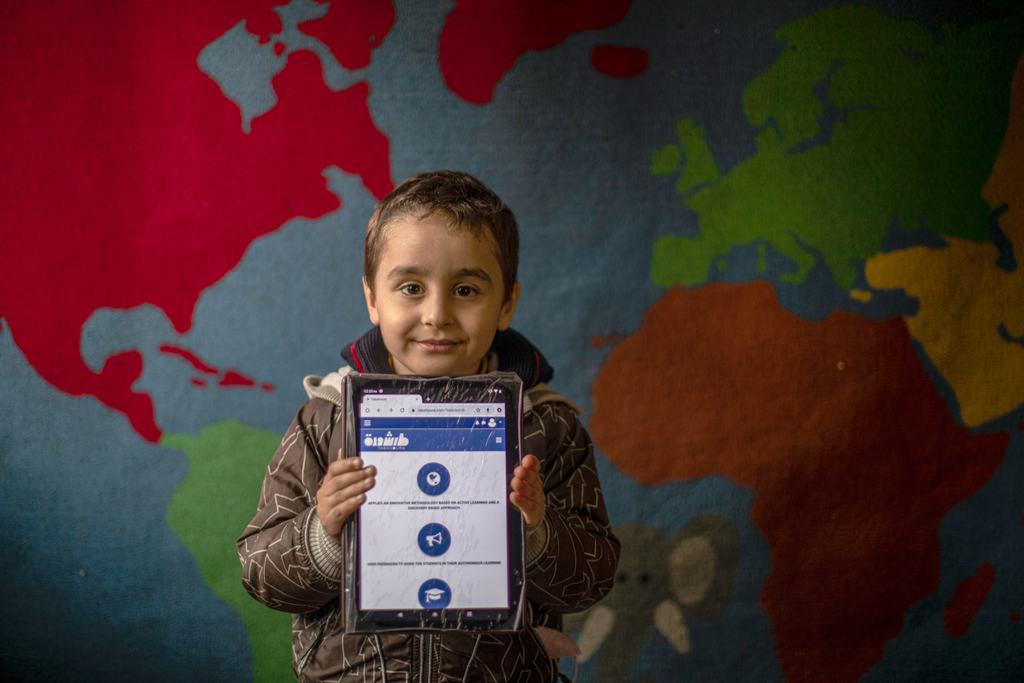

We're looking at the five vital aspects of nurturing care for the under-fives featured in our #5for5 campaign - today it's the role of play and why it's vital for so many reasons.

Theirworld’s #5for5 campaign has been calling for countries to invest in early childhood development – including nutrition, health, learning, play and protection. 90% of a child’s brain is developed by the time they are five years old, which means the early years are crucial.

This week, in our special Early Childhood Development Week, supported by Conrad N Hilton Foundation, we take a look at each of the five key areas of nurturing care, bringing you a snapshot of why it’s important and what world leaders are doing to give children in developing countries a better chance of a prosperous life.

Play

It should be the most natural thing in the world to do – and yet many children don’t get the opportunity to learn how to play. Every child needs to play to develop properly. Without it, their chances of reaching their full potential are lessened.

What’s happening?

If under-fives miss out on critical communication, early learning and play, this can significantly impact a child’s brain architecture and ability to learn basic skills.

Children learn so much through play – such as what sinks and floats; mathematical concepts, including how to balance blocks to build a tower; and literacy skills, such as trying out new vocabulary or storytelling skills and “acting out” different roles. They meet their first friends through play. Play is crucial to gain any life skills.

Why is it important?

“Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning,” according to the Fred Rogers Centre for early learning in Pennsylvania. “But for children, play is serious learning. Imaginary play helps children develop some necessary survival skills.”

The first years of life shape a child’s future into adulthood. This is when the most significant brain development happens, particularly in the first two years of life. Lack of play and communication, known as “under-stimulation,” can have long-term negative consequences on a child’s learning and physical and mental health.

What needs to be done?

Tens of millions of children around the world are regularly deprived of opportunities for play. In many developing countries, the time for play is often displaced by the chores and responsibilities that are so familiar to children growing up in poverty.

Many children are forced to abandon their education, even at a young age. Instead they are expected to tend to the family farm or herd, carry water long distances, or assume a range of domestic roles more traditionally carried out by adults – cooking, laundry and day care for their younger siblings.

Many children are forced into hazardous jobs that not only present risks to their health and safety, but require long, arduous hours of work every day.

We don't stop playing because we grow old; we grow old because we stop playing. Playwright George Bernard Shaw

What is being done?

In many developing countries, there is not the focus on play – many children are just trying to survive. But things are slowly swinging in the right direction. Take Chile, for instance, where children typically do not learn to read or even begin working with the full alphabet until around five years old. They concentrate on play.

- Why nutrition is vital for young children’s bodies and minds

- How small steps can help prevent millions of baby deaths

- Learning helps young children fulfil potential

“Early childhood education has not, in Latin America in general, been thought of as education,” said Catherine Snow, an expert on children’s language and literacy development at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

The BRAC education programme has become the largest secular and private education system in Tanzania, reaching a number of regions with education programmes that include the Play Lab Project.

Janeth Malela, project manager said: “Our Play Labs are designed and decorated in terms of five corners, we have one corner for imagination, innovation and creativity. The approach is: let the kids children play, get them used to being in groups.”

International bodies, such as the United Nations and the European Union, have also begun to consider and develop policies concerned with children’s right to play, with the educational and societal benefits of play provision and with the implications of this for leisure facilities and educational programmes.

More news