Supporting Early Childhood Education Teachers in Refugee Settings

Early childhood education is crucial to all children - but especially for child refugees, many of whom have suffered significant trauma. However, access to quality early learning is often extremely limited, poorly resourced and chronically under-funded. That is the conclusion of a new Theirworld report which analysed ECE provision in refugee settings around the world. Theirworld believes that quality ECE can be delivered to every refugee child if teachers are equipped with the right knowledge and tools. Our report - Supporting Early Childhood Education Teachers in Refugee Settings - identifies four key ways that this can be achieved.

Executive Summary: Supporting Early Childhood Education Teachers In Refugee Settings

Introduction

The provision of early childhood education (ECE) for refugees is extremely limited in many settings. Where it does exist, programmes are often poorly resourced. While all refugee education is underfunded, ECE is particularly underfunded and under-supported.

High-quality ECE can be a powerful avenue for helping young refugee children manage their trauma and for supporting their well-being in the short and long term. A wide body of evidence points to the transformative potential of ECE for young children, their families and their communities. For young refugee children who have experienced the trauma of conflict, displacement and separation from, or the loss of, family members or friends, ECE can support the healing process and cognitive, emotional and physical development.

Research has consistently shown that this phase is crucial for children’s healthy development. Refugee children may remain in displacement for much or all of their school years. Providing them with quality ECE is essential for supporting their healing, preparing them for learning and setting the foundation a successful future.

This report examines the landscape of ECE in refugee settings and the professional development available for ECE teachers. We reached our findings and formulated our project concept through

an extensive literature review, lengthy consultations with dozens of experts in early childhood education and development and refugee education, and by mapping of ECE programmes or providers serving refugees in challenging, poorly resourced settings.

The report identifies significant gaps in access to early childhood education and in support for professional development.

Theirworld’s goal is simple: to provide quality early childhood education for every refugee child, delivered by caring teachers equipped with the knowledge and tools to support their development. (‘Teacher’ is used to refer to anyone leading or supporting educational programming for refugee children in centre-based settings, though they may or may not be staff or salaried teachers.)

We propose avenues to support early childhood educators’ professional development, in recognition of their essential role. We aim to provide teachers, who are often refugees themselves, with the knowledge, skills and learning community they need to ensure that refugee children are given the best possible start in life and the best chance at having healthier and successful futures.

Our proposals are needed, feasible and scalable. Implementing these proposals will require the meaningful engagement of partners, globally and locally, who believe in the tremendous benefit and potential of ECE.

Background

Globally, ECE has short- and long-term benefits for the health and well-being of children and their communities. In a UNICEF analysis of low- and lower-middle income countries, more than three times as many children who attended ECE programmes were on track to achieve standard literacy and numeracy skills as children who did not attend.

ECE, which is widely accepted as applying to 3- to 6-year-olds, also brings significant returns on investment, particularly in learning and school completion. A dollar invested in pre-primary services for young, disadvantaged children could yield a return of 10 cents annually every year of their life.

Refugee education has become an increasingly important priority for the international community. This is reflected in the work

of Theirworld and other partners that advocated for refugee education and helped establish Education Cannot Wait, a fund set up in 2016 that has mobilised $695 million to support refugee education around the world

ECE – A Global Shortage

• In 2017, half of pre-primary-aged children globally were enrolled in pre-primary education. The ratio was 23 percent in South Asia, and between 30 percent and 33 percent throughout Africa.

• Across low-income countries, the pre-primary enrolment ratio was only 22 percent, and in lower-middle-income countries, it was 36 percent.

• ECE coverage in refugee environments is very likely to be even lower than in host communities, with extremely limited access; only nine percent of 26 humanitarian response plans in April 2018 included a focus on early learning.

• As of 2016, 4 percent of the world’s pre-primary teachers lived in low-income countries, which are however home to almost 17 percent of the world’s pre-primary age children.

• As pervasive and complex as these challenges are in LMICs, they are even more complex in refugee settings within these countries.

Source: UNICEF

The obstacles

ECE for refugees remains underfunded and under-supported in conflict-affected areas, with limited allocation from emergency and development aid budgets.

There is also a dearth of evidence on what works in ECE in refugee settings, whether in the Middle East, Africa or South Asia, the parts of the world that currently have the greatest concentrations of refugees. This is a large part of the reason Theirworld embarked on this research.

We found that although much is known about what young children facing adversity and trauma need, there is an absence of substantial guidance on how to deliver ECE in refugee settings. While some guidance can be drawn from ECE efforts in low-income countries and from early childhood development (ECD) programming in humanitarian settings, which focuses on a broader range of issues including health and nutrition, little exists for ECE programming.

In particular, guidance on support and training for ECE teachers is very limited.

Professional development must be tailored to the specific needs, contexts, experience levels, demographics and sociocultural and linguistic backgrounds of teachers in refugee settings, which vary widely. While standards and accreditation systems for training can be useful, this report argues that these should not be developed or applied at a global level, given the need for training to be highly responsive to context and teacher experience.

The educational systems of many low- and lower-middle income countries also often lack the capacity and resources to provide ECE to their own citizens – the ‘host community’ children – let alone refugees, while some have policy restrictions limiting refugee education. While professional development is often seen as “implicit” to ECE programming, especially when resources are scarce, it is key to unlocking change in ECE for refugees.

Our concept

Our approach is based on developing and supporting the skills of teachers, given that non-governmental organisations, charities and agencies that provide ECE often have limited capacity and resources to provide training and professional development opportunities for teachers. We have identified four ways to achieve this:

1. Make the Science of Early Childhood Development and Learning More Accessible

Training for ECE teachers in refugee settings is usually extremely limited. When teachers are trained, they are often not fully equipped with strategies that can help children achieve their greatest potential. Teachers may learn activities for working with students but often do not receive much training on the science of early childhood development. Understanding the science of ECD has revolutionised the way the world approaches support for

young children. Learning about the basic science of ECD, including the impact of trauma and the value of nurturing relationships, can help teachers understand what strategies are effective with their students and why. This can also help make teachers more effective and confident.

There are very few accessible resources on the basic science of ECD that target teachers. While teaching resources must always be tailored to the geographic context in which teachers are operating, we believe theoretical training on the basic science of ECD can be more universal with local examples added when possible.

We are seeking to make these resources accessible to ECE teachers working with refugee children. Resources on the science of ECD should be translated into the language required and delivery made adaptable to all appropriate devices and modalities. Though some resources do already exist to make the science of early childhood development more accessible, they are often aimed at non-teaching audiences such as policy-makers or designed for audiences with high speed internet. They often take the format of massive open online courses (MOOCs) or online and in-person training courses, which can be hard for teachers operating in refugee settings to access. To reach teachers without internet access or high data bandwidth, radio and WhatsApp- or SMS-based resources will need to be explored. Lessons can be learned here from the pandemic, which has necessitated lower tech approaches.

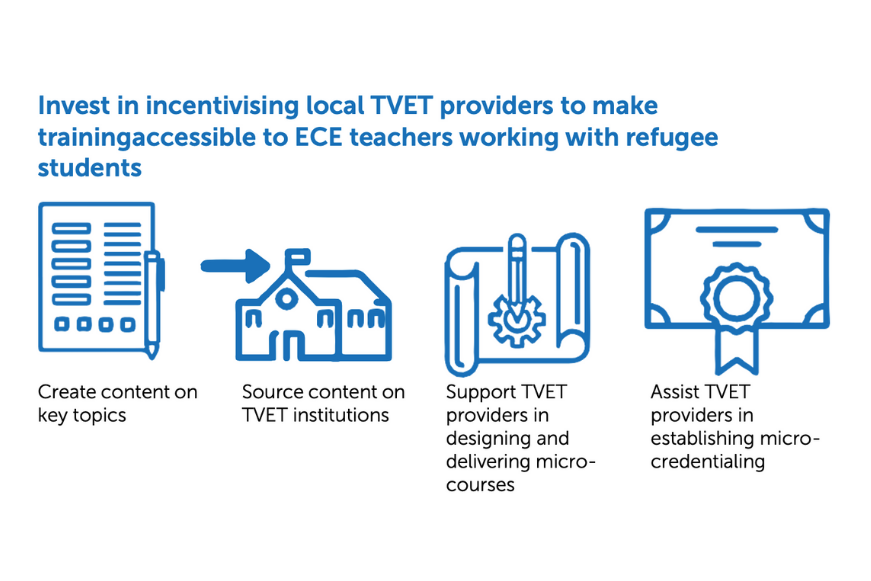

2. Partner with TVET Institutions in Refugee Settings

In addition to making the science of ECD more accessible to teachers, providing teachers with practical, context-relevant training and support is essential. Our research pointed to the viability of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) institutions to deliver this kind of support. TVET institutions have great potential to support refugee ECE through the co-design and delivery of training courses and offering micro-credentials and certificates.

Many implementers of refugee education, even those offering some form of professional development, express a desire for more training and support opportunities. Local TVET institutions are an untapped resource for providing formal training, peer learning opportunities and recognition of ongoing teachers’ work-based learning.

TVET institutions could be well-positioned to provide contextualised, work-based training and support in the settings where these teachers work. Theirworld and partners would create the content, provide it to TVET institutions and support them in designing and delivering courses for teachers. The institutions would be assisted with providing micro-credentials for teachers who completed courses and provided incentives to do so.

Teachers working with young refugee children can often feel isolated, and their work is often not recognised beyond certificates from implementing organisations recording their participation.

They may be working in large, tented spaces, temporary shelters or small educational centres or community spaces located in or near refugee camps. Often, teachers are refugees themselves, and may not have opportunities to interact with peers. Locally designed courses and micro-credentialing would offer them a sense of peer learning and support, and strengthen their links with TVET institutions, which could be useful to their later professional opportunities.

3. Support establishment of communities of practice to foster collaboration and exchange between teachers and practitioners

In line with a significant body of global education evidence, our findings suggest that ongoing support for teachers during their service is critical, and communities of practice are one avenue to consider for providing this support. Given the tremendous value of building community among teachers and the power of peer learning, we recommend supporting communities of practice

for teachers working in refugee settings. These communities of practice may be local, national or regional, depending on the context, teacher needs and logistical constraints such as language. In many cases, they would likely be virtual to allow for participation beyond teachers’ immediate surroundings, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic, through high- or low-tech platforms. Building on the experiences of well-established models of communities

of practice, this approach would provide teachers with avenues for learning from their peers, offering and receiving pedagogical resources that they have found useful, and sharing their own challenges and successes.

4. Translate learning from local communities into broader evidence and resources through a hub or learning lab system

The limited evidence on effective practice in ECE in refugee settings generally – and especially on teacher professional development and support – is a major challenge. Given this, we propose implementing a learning lab or hub model in several different contexts to generate evidence on and to elevate effective and innovative approaches that have been developed and refined in context. As discussed, indigenous and local models for ECE

in refugee settings hold tremendous value, and a learning lab model would provide an avenue for identifying effective practices, understanding why they are effective, and sharing learning on these models globally.

Next steps

Theirworld plans to stage pilot projects in a small number of select countries where we have existing strong relationships, where there are large refugee populations and some existing practice or government commitment to ECE.

We believe our approach is scalable. It allows for the low- cost scale-up of teacher learning and support, while intensive monitoring and evaluation of the pilots would help establish an evidence base for the approach and lessons for adaptation and growth.

When it comes to teaching the science of early childhood development, the costs of expanding beyond the pilot phase would be low, once initial investments in licensing and adapting materials for audience and format had been made. They would also below for implementing organisations, who could build materials into existing training structures or add them as supplementary resources particularly where materials have been adapted for phone-based learning.

Similarly, the partnership with TVET institutions has limited scaling costs, as adaptation of course content would be pulled from existing expertise at the institutions and course delivery would draw from institutions’ existing infrastructure and methods.

Theirworld’s track record of advocacy for ECE and refugee education generally could be leveraged for both stages of the programming, should political barriers to expansion emerge.

Our first goal is a modest step to unlock big change: bringing together partners. We’re seeking to build a coalition of partners from different sectors to build on existing expertise, resources and approaches in this area. This coalition would ultimately support the adaption and co-creation of resources and roll-out of pilots in several countries. With our track record of success, we’re convinced this step will lead to significant impact on the lives of millions of children in the coming years.

We are seeking to create a consortium of partners to support development and delivery of our pilot projects in the following ways:

• Further development of the concept

• Development of ECE and TVET materials

• Outreach to possible partner organisations and pilot sites

• Implementation of pilots

To the fullest extent possible, Theirworld aims to connect with partners already working in this area to build on existing resources, approaches and knowledge.

Next resource