Health and education convergence

This page is about the concept of health and education convergence and how it is vital to successfully improve all aspects of people's lives.

What do we mean by health and education convergence?

Improving education doesn’t take place in a vacuum. Education underpins all of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals – but it is particularly critical that health and education are addressed together.

Access to education improves health outcomes for individuals, families, and communities while better health improves an individual’s chances at being educated. Addressing health and education together is important, since the benefits are mutually reinforcing.

Quality education, especially for girls, means individuals can better look after their own health and that of their children. So the health benefits of education extend long into the future.

Why is health and education convergence important?

Many attempts to improve health depend on someone being able to translate advice and knowledge into behaviour in their daily lives.

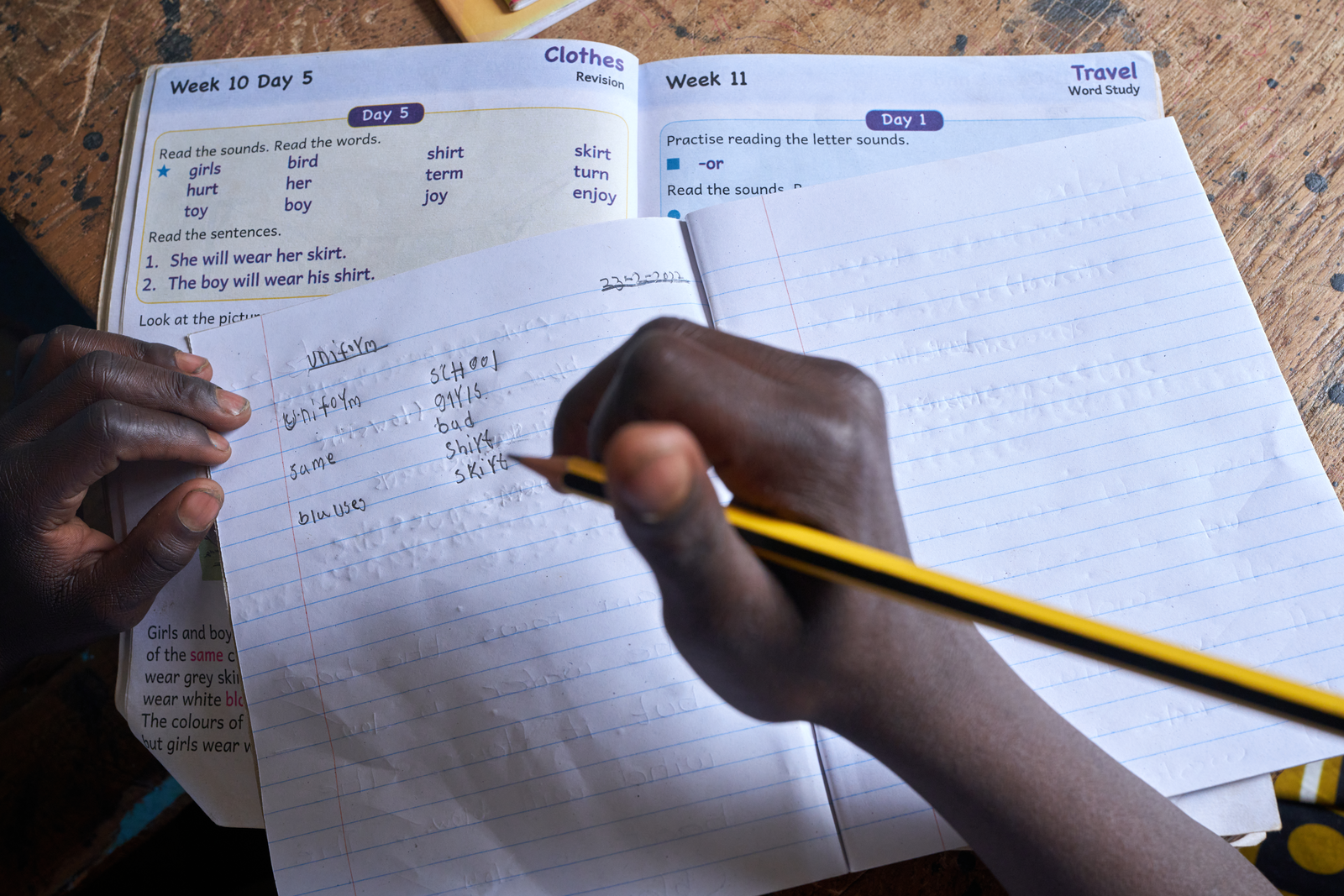

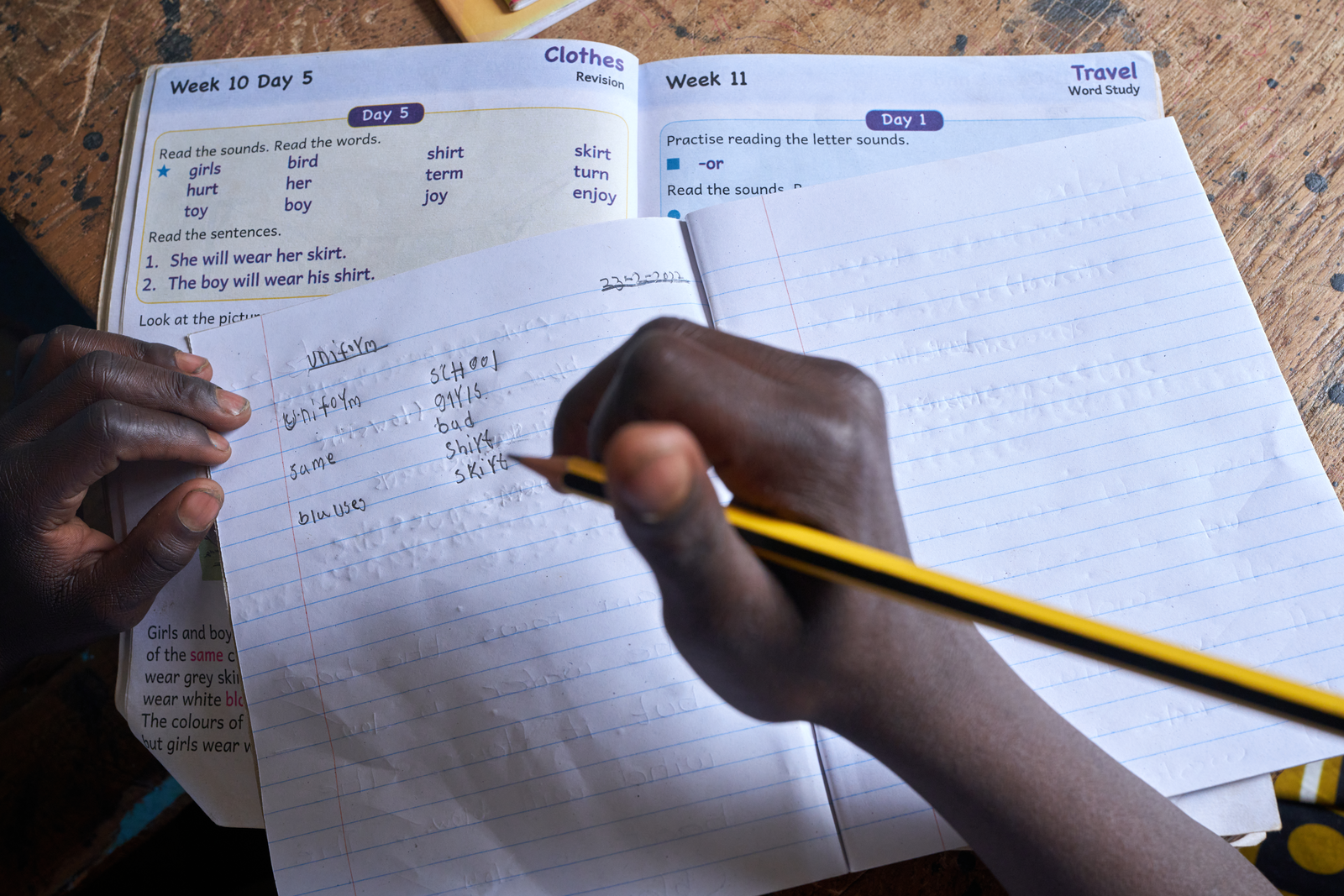

Without a reasonable level of education, people may find it difficult to understand and act on advice about good health practices. Education gives people the tools – such as literacy skills – and the knowledge they need to make informed decisions about health for themselves and their families.

Poor health can have a negative effect on efforts to improve education, as illness can keep children out of school and prevent them from learning.

Broadly, convergence is about bringing together all the different efforts to improve people’s lives, in this case, education and health to help children. It’s important that health and education challenges are addressed together.

Theirworld President Sarah Brown said: “For people who want to live better lives, it all joins up and schooling does not exist without a daily meal and good health, access to water and sanitation and a safe school journey home.

“As soon as we find a better name to describe what has so far been called convergence, the quicker we will find focus and forge stronger partnerships across the development community.”

Education gives people the skills to use health care services, to recognise illness and to take preventative measures, all of which improve the health of the communities they live in.

A child whose mother is illiterate is 50% more likely to die before the age of five than one whose mother can read and write. Mothers with education are better informed about how to prevent diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria.

In 2012, 6.6 million children under the age of five died of preventable diseases in lower and middle-income countries. If all of the women in those countries had finished primary school at least 15% of these deaths could have been prevented – a million children in a year. If all the women had finished secondary school, three million young deaths would have been avoided.

In much of sub-Saharan Africa, girls with no education are four times more likely to have babies than those at secondary school. Education empowers girls and young women with knowledge to make their own health and reproductive choices.

Also, 3.5 million child deaths could be prevented in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030 if mothers were educated to lower secondary level.

In the fight against HIV, education provides the best way for young people to learn about risky behaviours and negotiate and practise safer sex. At least 85% of literate women in sub-Saharan Africa know where to get tested for HIV, compared to 52% of those who cannot read and write.

Studies show that those with education are far more likely to use bed nets properly and be aware of the symptoms and treatment of malaria. If a mother has a secondary education, the chance of her children carrying malaria parasites is 44% lower than the average.

Diarrhoea is the second biggest cause of death in young children and the leading cause of malnutrition – but diarrhoea is preventable and treatable. When children and teachers in day-care centres and schools wash their hands properly, diarrhoea cases are reduced by at least a third.

Where did the idea of convergence come from?

The Lancet Commission on Investing in Health proposed a “Grand Convergence” of health goals that joins up all the health initiatives around the world. They suggested focusing the international community on three key goals – an under-five mortality rate of 16 in 1000, an annual AIDS death rate of eight in 100,000 and an annual death rate from tuberculosis of four in 100,000.

Writing in a recent Huffington Post blog, Theirworld President Sarah Brown said: “This is to be hugely welcomed but I hope one more converging factor can be taken on board as soon as possible. None of these goals can be reached without investment in education.”

“In this ‘Grand Convergence’, let’s not leave education outside the door. Investing in health without investing in education is a non-starter if we are serious about success. So alongside the 16-8-4 convergence plan targets for reducing infant mortality and AIDS infections and TB, we should add a new figure – 16-8-4-0. A zero exclusion rate from education.”

Next resource