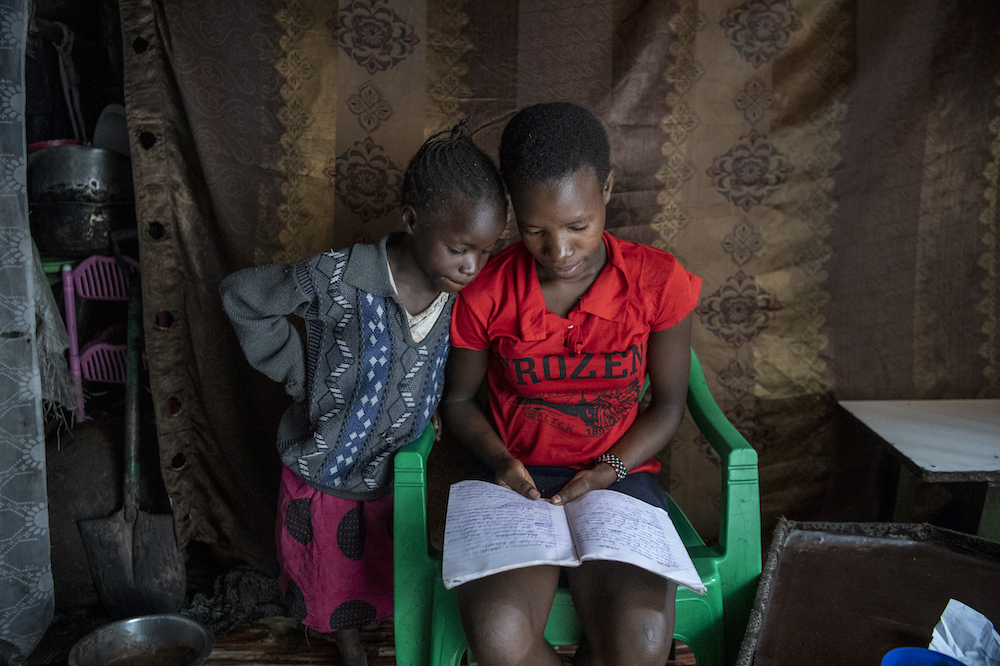

Lured into work over summer holidays, many Indian children will never return to school

Child labour, Right to education

Agents often break promises to bring back children from factories or farms to their villages in time for the new school session.

As schools break for summer, human traffickers across India are convincing impoverished parents to send their children to work over the holidays in factories and farms, campaigners said.

Anti-trafficking groups are urging the government to crack down on child labour during the two-month break, warning that many children never return to school once they start working.

“In this season, playgrounds and neighbourhood shops become hunting grounds for traffickers,” said Kuralamuthan Thandavarayan of the International Justice Mission, an anti-trafficking charity.

“They track children from poor families and convince parents that it is a waste of time to allow their children to play or stay home when they can earn instead.”

There are an estimated 10.1 million workers between the ages of five and 14 in India, according to the International Labour Organization.

More than half of them toil on farms and over a quarter are in the manufacturing sector embroidering clothes, weaving carpets, making matchsticks and bangles.

“In many villages, with both parents out working, teenagers at home during summer break are lured by recruiters looking to hire cheap labour in the (textile) mills,” said Joseph Raj of the non-profit Trust for Education and Social Transformation.

Other children join their parents in brick kilns, where they work between November and June, when the rainy season begins. The recruitment and payment systems in these kilns trap seasonal migrant workers in a cycle of bonded labour, according to a 2017 report by the rights groups Anti-Slavery International and Volunteers for Social Justice.

Wages are low and often paid at the end of the season, and families are forced to put their young children to work to make 1000 bricks a day, which allows them to make the minimum wage, said the report.

“Agents promise to bring the children back to the village in time for the new academic session. But the problem is that many don’t return,” said Krishnan Kandasamy of the National Adivasi Solidarity Council, an advocacy group.

Tamil Nadu state government data showed that nearly 30% of the 1821 people rescued from debt bondage in 2017 were children.

“It starts out as children helping their parent but slowly they take on more work that involves longer hours,” said Kandasamy.

Right to education

More news

“Education can help to end child trafficking”