Gang wars mean school can be a battleground in Honduras

Barriers to education, Right to education

Education is under attack around the world because of armed conflicts - but many schoolchildren live with the threat of violence that doesn't make global headlines.

The clatter of bullets piercing the school’s roof sent pupils running for safety. Four of them and their teacher were wounded.

The February 27 attack on the Maximiliano Sagastume school in a northern district of Tegucigalpa was just one violent episode in a turf war between heavily armed gangs in Honduras.

Such occurrences are so common, they are subsumed quickly into the country’s news cycle and barely register outside its borders.

For the pupils, it meant no classes for eight days as police set up a perimeter to protect them from the local criminal outfit, part of the Mara Salvatrucha gang, or MS-13.

Members of the Military Police stand guard as students arrive for class at the Maximiliano Sagastume school in Sagastume on March 17.

Such protection is also afforded to other schools and colleges in the capital, stretching police and army forces that seem unable to counter the reach of the feared gangs.

MS-13 and its chief rival, Barrio 18, and other smaller outfits assert control over different neighbourhoods, preventing residents from freely moving between them and frequently clashing in exchanges of gunfire.

The phenomenon is the same across the so-called Northern Triangle of Central America comprising Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala – a region plagued by poverty and vicious violence where gangs dealing in drugs and weapons have supplanted the rule of law.

A spokesman for a combined national security force in Honduras known as Fusina, Lieutenant Colonel Mario Rivera, told AFP that hundreds of personnel were involved in securing schools in Tegucigalpa and in other Honduran towns.

A teacher at one school with 300 pupils said on condition he not be identified that some of the students were gang members and their threats against classmates or teachers often meant that police protection had to be brought in

A teacher gives a lesson at the Maximiliano Sagastume school.

In the case of Maximiliano Sagastume school, although the four pupils and the female teacher were slightly wounded and the police perimeter was set up, many parents subsequently transferred their children to other schools.

The families’ sense of panic was heightened because 14-year-old twin girls were abducted after the shooting and their mutilated bodies were found days later.

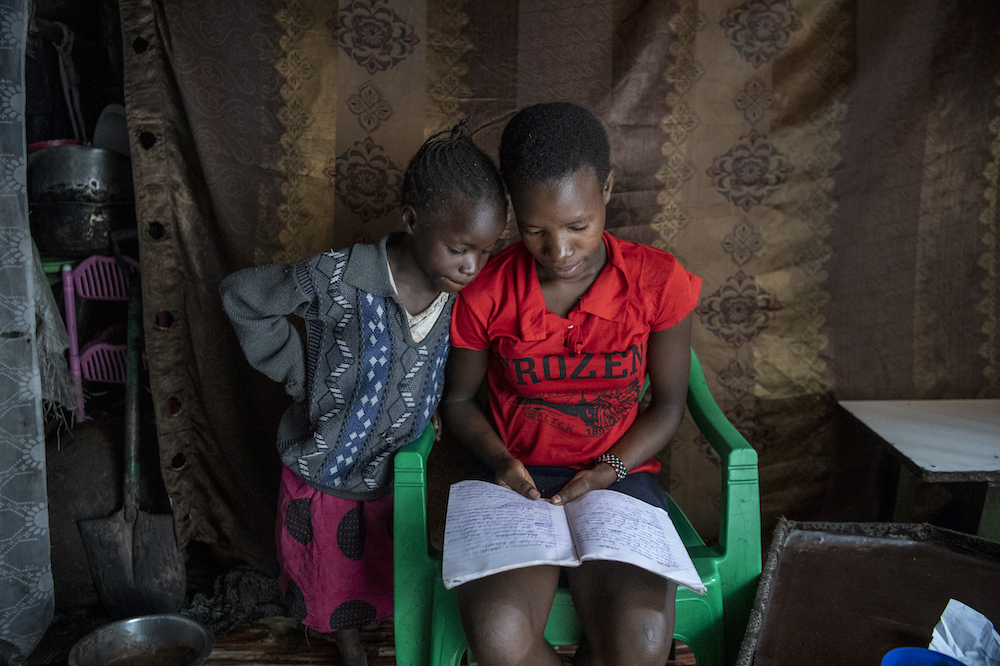

Honduras education

Children go to school for an average of seven years in urban areas and only 4.3 years in rural areas, according to UNICEF.

The main causes of these low numbers lie in inadequate teaching, scarcity of teaching materials, poor physical learning environments and limited interaction between schools and communities.

“Here people sleep with one eye open,” said one policeman standing guard.

He was part of a deployment posted near the school. Police patrols on motorbikes and squad cars frequently nosed around the neighborhood, called Sagastume I.

“If we need to, we can call in reinforcements,” the officer said, indicating the radio attached to his leather belt.

The school, located on a hillside, also features metal bars and a three-metre (10-foot) high wall topped with barbed wire.

To the north of it, separated by a stony hill with no houses, is El Picachito, a district claimed by the Combo gang. Just south of the school is an area lorded over by MS-13.

The school and the surrounding concrete homes sit in a sort of no-man’s land often fought over by the two gangs.

“We’re in the middle of the firefights. At night, it’s like a war zone,” said Napoleon Zuniga, a 70-year-old owner of a small shop in Sagastume I.

“Over there the Combos shoot, and then down there it’s the MS,” he said.

Police stand guard as a young student is taken to class.

A police officer said the February 27 shooting appeared to come from Combo gang members “to cause fear among residents and the opposing gang.”

He added: “All they want to do is take control of the zone to be able to sell drugs and extort the businesses.”

Nationwide in Honduras, police estimate MS-13 and Barrio 18 together have about 25,000 active members. But there are no hard figures. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, for instance, puts the combined number at 12,000.

Nevertheless, the effect of the gangs on the homicide rate is clear. Honduras’s rate of murders is nearly 10 times the global average, according to the World Health Organization

More news