Cambodia’s leader promises big spending on education ahead of election

Right to education

Prime Minister Hun Sen says 25% of the national budget will go on schooling - but critics say a new system will penalise children from poorer families.

Cambodia’s ruling party has thrown resources at a weak education system ahead of elections this weekend as it tries to entice young voters and drain resentment over low-paying jobs.

The school system was completely destroyed in the 1970s by the Khmer Rouge, who executed teachers as perceived enemies of the hardline Communist regime. Despite efforts to rebuild, standards still lag far behind Cambodia’s Southeast Asian neighbours.

Now strongman prime minister Hun Sen is promising schooling for all, hiking education spending to $850 million this year – a record quarter of the overall government budget.

“I want every district to have a high school, every commune a junior school and every village a primary school,” he said in a recent campaign speech.

The premier is all but guaranteed to extend his 33-year grip on power in poll on July 29 after a crackdown on dissent in the run-up to the vote.

That includes the dissolution of the only viable opposition party by the Supreme Court in November, while swipes at civil society and the media have snuffed out critical voices.

But in a country where a third of the 15 million population is aged under 30, he has also carefully targeted his appeal.

He speaks regularly at graduation ceremonies, promising jobs and opportunity to thousands of young people nervous about their futures in a country reliant on low-skilled labour.

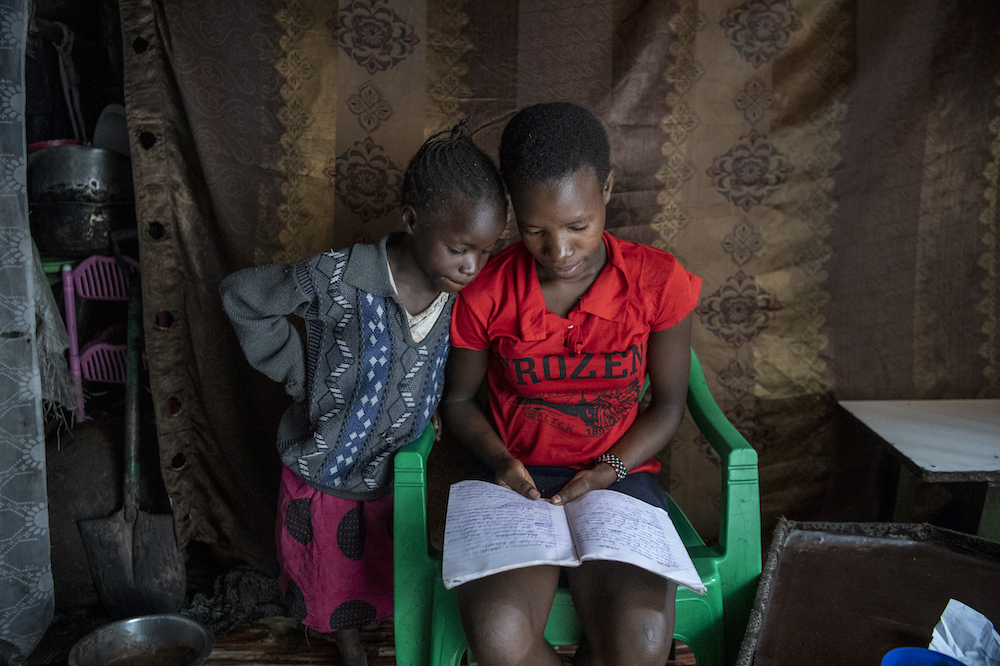

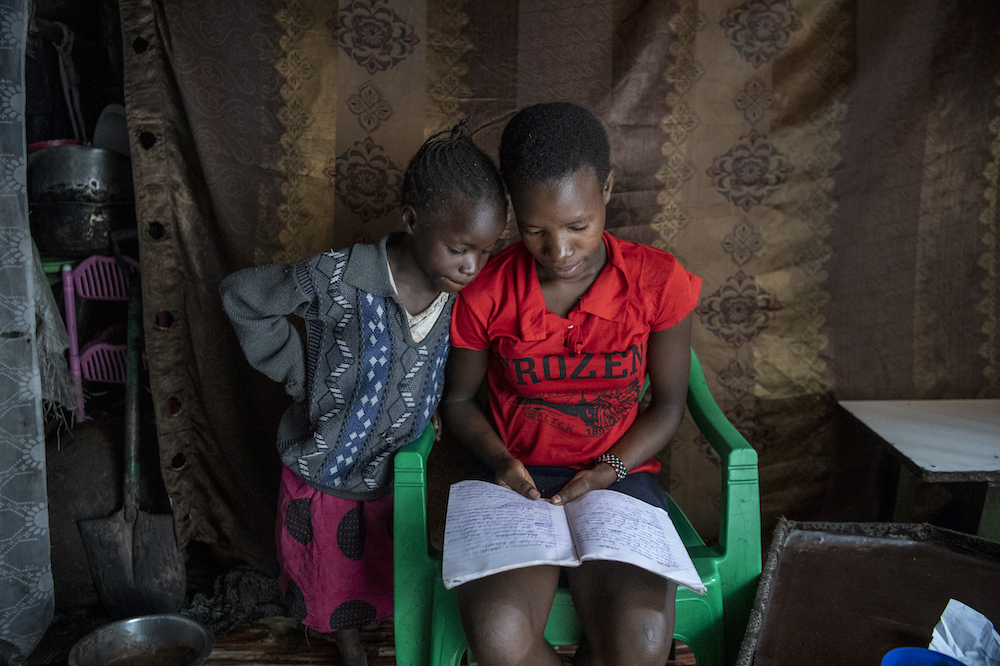

Out of school in Cambodia

Over 57,000 primary school-aged children – 2% of the total – are not enrolled in any form of education, according to a 2015 report by the Cambodian Consortium for Out of School Children.

Some 300,000 Cambodians enter the job market each year, often without qualifications, according to the United Nations.

But major industries such as the garment sector, which employs nearly 750,000 people, are acutely vulnerable to automation and changing wage patterns.

At the same time education does not always equate to a well-paying job and secure future.

“There are many students graduating… but few jobs,” said So Van Veasna, who earns $200 a month in an administrator’s position after graduating from law school.

The gap between aspiration and reality encouraged students to line up in support of the now-defunct opposition in the last general election.

They will have a job after they graduate because here we can train them in everything. Men Solaneth, high school teacher

Before then the government had been on a school-building frenzy. Many of those institutions were named after Hun Sen by officials keen to curry favour with the premier.

But a marked drop in support for the ruling party during the 2013 polls has compelled it to take a more active role in the school system’s future.

Hun Sen has supported the founding of “new generation” schools across the country – state-of-the art institutions boasting science labs and tablet computers, with longer class hours and a broader curriculum.

“They will have a job after they graduate because here we can train them in everything,” insists Khmer literature teacher Men Solaneth at Sisowath High School in the capital.

At nine and growing, the “new generation” schools have surged in popularity with hundreds enrolled, forcing administrators to move from an open admissions policy to a testing and lottery system akin to US charter academies.

“The school has good facilities, so the students take pleasure in learning,” says high school student Seng Sreyleak, who was accepted through the lottery.

Critics caution the new admissions system will likely favour well-connected students, especially if – as has been mooted – tuition fees are introduced.

But Sam Kamsann, deputy principal at Sisowath High, rejects these suggestions. He said: “We allocate 30% of seats to children from poor families and we help all students fairly.”

Sam Rainsy, a leading opposition figure who lives in self-exile in France, dismissed the education spending burst as misleading, saying the total amount in relation to GDP remains one of the lowest in the region.

Rong Chhun, a member of the Cambodian Independent Teachers’ Association, told AFP that most schools across the country don’t have enough books, let alone fancy computer labs.

About 100 kilometres north of Phnom Penh, talk of a “high tech” school revolution feels impossibly remote. The metallic roof leaks at Tanei Primary School and teacher Yi Sareth often has to buy chalk out of his own pocket.

“We have nothing, I’m sorry for my students who sometimes do not even have a book,” he says.

More news