‘Children are like little sponges’: early learning can set them up for life

Childcare, Early childhood development, Safe pregnancy and birth

Learning is one of the key areas of nurturing care in Theirworld's #5for 5 campaign that very young children need to reach their full potential.

Children don’t start learning at home or at school – they start learning while in the womb, where they can begin to recognise words.

And they’ll never stop learning. That process will continue for the rest of their lives.

Learning is key – along with proper care and stimulation – to giving a child the best chance to reach her full potential.

There’s no more important time in a child’s life than the first 1000 days – from birth to age three. Their brains are developing faster than at any other time. In fact, by age five a child’s brain is 90% developed.

“Learning starts before we are born and keeps going,” said Dr Eva Lloyd, Professor of Early Childhood at the Cass School of Education and Communities, University of East London.

“Children, especially in the early years, are like little sponges, absorbing all the information around them and then actively making sense of it.”

While there is much “active and formal” learning in the developed world, many poorer nations simply don’t have the same resources. But getting the foundations right in the early years can help them to have a more educated and skilled population.

This is why early childhood development is climbing up the global agenda and receiving more attention than before.

Theirworld’s #5for5 campaign highlights the need for countries and donors to invest in early years care and pre-primary education.

Learning is one of the five key areas of nurturing care that children under five need to grow and develop.

Professor Lloyd said: “Parents can feel the pressure to be involved in ‘direct learning’ but it’s also good to give your children enough space to learn by themselves and explore their world through their play. Playing outside is particularly important.

“We are lucky in the western world that our early year settings and nursery schools provide lots of stimulation which creates new experiences too.”

Educational psychologist Mike Hughesman believes it’s not the quantity but the quality of stimulation in the early years that counts.

He told Theirworld: “Learning and stimulation can be considered as part of the essential nourishment that the developing infant needs to enable the cognitive capacity of the brain to grow and remain healthy.

“Early experiences of nurturing, feeding and care are rich sources of new learning – the synchronous rapport that usually develops between mother and child becomes a bond that is fundamental to social learning and the child’s sense of security and wellbeing.

“We do know that they also learn from passive stimulation – notably TV is an attention grabber – and through watching the activities of other children.

“But the development of key skills – including posture, balance, standing, walking and fine co-ordination of hand and eye – all require activity through physical effort and learning opportunity.”

But what about young children who are having to develop in a traumatic situation, like a war zone or extreme poverty?

Professor Lloyd reviewed research on the impact on children’s learning in refugee camps and in areas of conflict. While being realistic, she remains hopeful that little ones being raised in conflicts can still reach their potential.

She said: “We saw from the children left in Romanian orphanages that, without proper care and stimulation, the child will become badly disabled.

“But I hesitate to generalise on this. There is of course going to be trauma and deprivation which may well affect children in conflict zones. However, there is great plasticity in children’s learning and the adolescent years are extremely important too.

“So, there is still much potential for children brought up in difficult circumstances. What the studies we looked at found was that children just wanted to things to be normal – to go to school, have a normal family environment.

“We must remember that children need a childhood and not to be constantly directed by adults.”

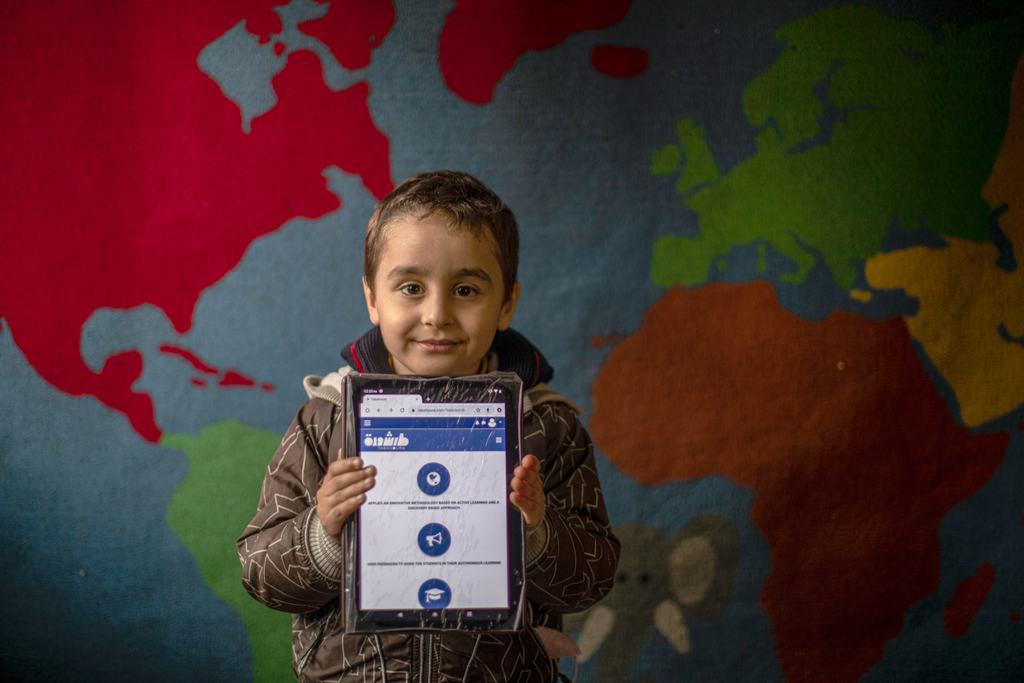

Learning can be even more vital during periods of high stress for young children, like conflicts. They need “safe spaces” to allow them to play, relax and learn away from the threat of violence.

In conflict areas, UNICEF’s safe spaces allow young children to learn and play – and relax and learn away from the threat of violence.

“I love jumping rope, drawing pictures and playing the tambourine,” said Asia. She can do all three at UNICEF-supported child-friendly spaces at a camp for Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh.

In Syria, children can learn through play and socialising at underground playgrounds like the Land of Childhood. There they can enjoy playing on see-saws, carousels and swings, bringing a sense of normal life back.

These are vital interventions for vulnerable children. For, as Mike Hughesman, warned: “We know that children deprived of consistent nurturing attachments during these early years can suffer from emotional problems that persist throughout childhood and even into adult life

“Under-stimulation during the early years from birth to five can occur for any number of reasons. But while children can be remarkably resilient, the disadvantaging effects are distinct and can have a lasting impact.”

More news

MyBestStart programme gives young girls the education they deserve