As millions need urgent food aid, why nutrition for young children is also a long-term crisis

Childcare, Early childhood development, Health and nutrition, Safe pregnancy and birth

Drought and conflict are causing massive hunger emergencies - against a backdrop of one in four children in developing countries already suffering chronic malnutrition that could affect their development.

The world is watching in horror as yet another humanitarian catastrophe is unfolding.

Twenty million people will die unless urgent action is taken to tackle hunger crises in four war-torn countries. Immediate funds are needed for Yemen, South Sudan, Somalia and northeast Nigeria or “people will simply starve to death” warned United Nations humanitarian chief Stephen O’Brien last week.

And millions more are facing starvation in Kenya and Ethiopia because of drought and conflict.

“Hunger on a massive scale is looming across East Africa,” said Disasters Emergency Committee Chief Executive Saleh Saeed, launching an appeal today.

“More than 800,000 children under five are severely malnourished and without urgent treatment are at risk of starving to death.”

That devastating news comes against a backdrop of 159 million children in developing countries – that’s one in four – already suffering chronic malnutrition.

Two million children die every year simply because they don’t have enough to eat or have no access to clean water or proper sanitation.

While famine is at the forefront of the UN’s focus in terms of saving people’s lives right now, the undercurrent of a malnourished population has drastic, long-term implications.

That’s why early interventions are vital if very young children are to get the best start in life. If a child is malnourished from the start – if carried by an under-nourished mother – the baby’s brain will not develop to its full potential and the child could suffer serious health problems later on in life.

During infancy, brain development uses 50% to 75% of the energy a baby consumes.

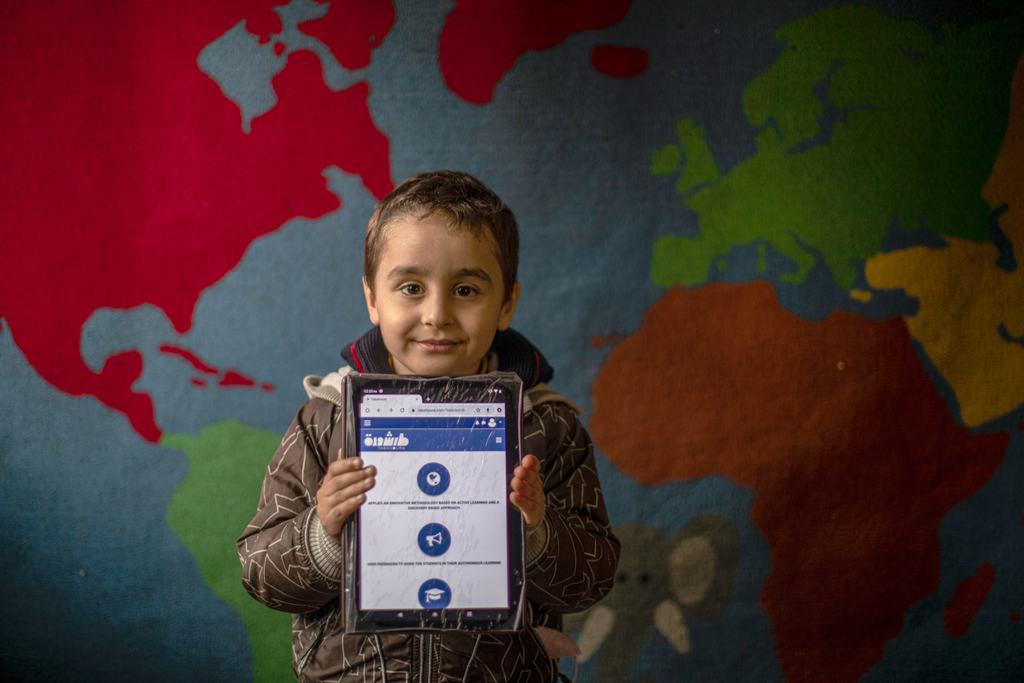

Theirworld has been campaigning for countries to invest in early childhood development – including nutrition, health, learning, play and protection. These are even more vital in humanitarian emergencies like the current hunger crises.

“In a crisis the youngest children are exceptionally vulnerable, not only to physical dangers but also to psychological trauma, toxic stress and poor development,” said Ben Hewitt, Theirworld’s Campaigns and Communications Director.

“The evidence of the crucial importance of focusing on the early years is widely known so every humanitarian response should include targets which explicit address babies and children aged zero to five.

“We know that 90% of our brain develops by the time we are five years old so the emergency response must go beyond physical support and include childcare, psychological support and early learning programmes.”

Chronic malnutrition in the womb and during the first 1000 days of life can permanently harm the growth of a child’s body and brain, according to non-profit organisation 1,000 Days, which champions the quality of a child’s life in the first three years.

“In addition to causing stunted growth (too short for age), chronic malnutrition can hamper brain development, weaken the immune system and increase the risk for serious health problems later in life, such as diabetes and heart disease,” say experts from the Global Nutrition Report in the book From Promise to Impact: Ending Malnutrition by 2030.

The UN children’s agency UNICEF revealed last year that 20 million babies are born with low birth weight – around a fifth of all births.

800,000 children under 5 will die if we don't reach them quickly. Don't delay. Donate: https://t.co/iTiSGV2GI6 and start #FightingFamine pic.twitter.com/Hkv39w3Ckp

— DEC (@decappeal) March 15, 2017

“Low birth weight is a major predictor of infant illness and death and puts babies at greater risk for long-term health problems,” says UNICEF’s report Building Better Brains: New Frontiers in Early Childhood Development.

Children, especially infants and toddlers, need access to the right foods because their bodies and brains need good nutrition for healthy growth.

A child’s brain is 90% developed by the time they are five years old. If there is not enough proper nutrition in a child’s diet by this time, not only will their body suffer but their brain will never be able to reach its potential.

An under-developed growing generation will ultimately affect how that generation looks after its country and the next generation. It’s a crisis spiralling out of control.

Leading childhood nutrition expert Charlotte Stirling-Reed, who specialises in infant and toddler nutrition, said: “The moment of conception, as well as before this, right up until a child’s second birthday marks a period of rapid development. Research shows that this is when the foundations for life are laid.

“Poor nutrition can affect not just an individual child and family but it can also have knock-on effects to future generations too.

“Poor growth and development can occur if children are malnourished and the risk of developing serious infections and diseases are also higher.

“Again research has taught us that good nutrition has been shown during this time to reduce the risk of chronic diseases, improve learning and performance, reduce infection risks and improve income and education attainment within families and even countries.”

The UN is warning that thousands of children are suffering and dying every day as a result of acute malnutrition or “wasting”. This occurs when a child loses weight quickly and becomes too thin for their height due to food shortages or as a side-effect of disease or poor water and sanitation.

“Wasting puts children at immediate risk of death and increases risk of chronic malnutrition and illness. Acute malnutrition often occurs in emergency situations,” according to UNICEF.

“Currently, 50 million children – one in 13 – are acutely malnourished and two million children die from acute malnutrition each year.”

So it’s not just the famine crisis and other emergencies that are to blame – long-term poverty plays a part.

More than 19% of children in developing countries are in families surviving on less than $2 a day, which is affecting their health and ability to fulfil their potential.

Worldwide almost 385 million children are living in extreme poverty.

“The effects of poverty are most damaging to children,” said UNICEF Executive Director Anthony Lake. “They are the ‘worst off’ of the worst off – and the youngest children are the worst off of all, because the deprivations they suffer affect the development of their bodies and their minds.”

Ana Revenga, Senior Director, Poverty and Equity at the World Bank Group, said: “The sheer number of children in extreme poverty points to a real need to invest specifically in the early years – in services such as pre-natal care for pregnant mothers, early childhood development programmes, quality schooling, clean water, good sanitation, and universal health care.”

Some key interventions for young children

Access to clean water and proper sanitation.

Foods like wheat, rice, and salt can be fortified with vitamins and minerals such as iron and iodine to provide increased nutrients without requiring consumers to buy different foods.

Vitamin and mineral supplements for adolescent girls, pregnant women, mothers, and children can ensure access to essential nutrients if they are not available through diet alone.

The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life (no other food or water). Breast milk is the best source of nutrition and health in these early months, supplying not only the right balance of protein, fat, and nutrients but also providing children antibodies to fight off illness. At six months, the WHO recommends adding solid foods to a child’s diet in addition to breast milk.

More news