Kailash Satyarthi criticises India’s plan to let children work in family business

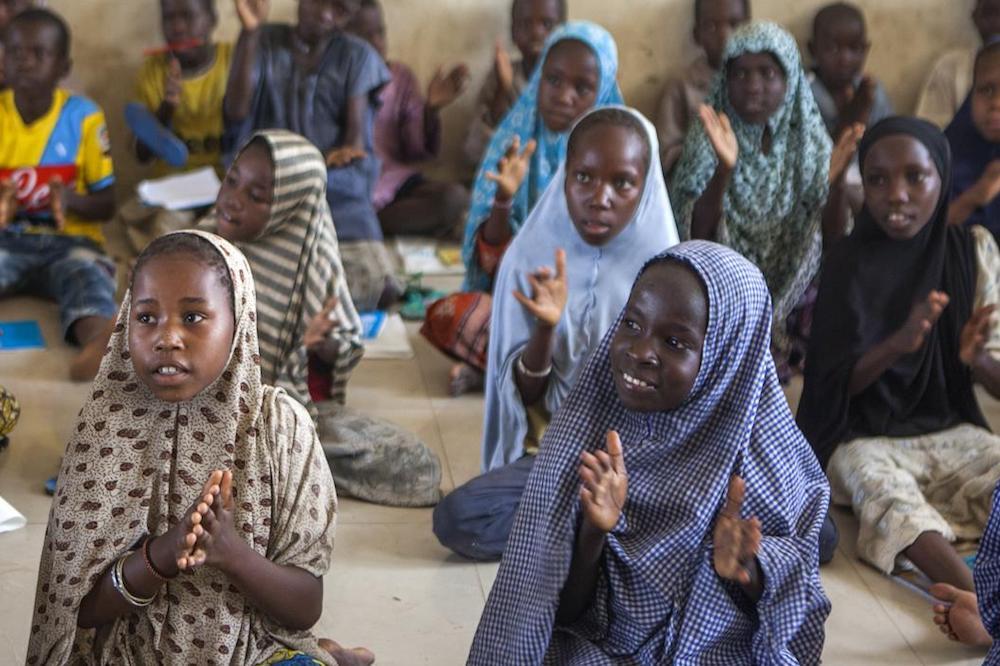

Child labour

Children protest against child labour at a school in Amritsar

India’s plans to allow children to work for family businesses and bar teenagers from employment in only a few hazardous industries are “regressive”, Nobel Laureate and child rights activist Kailash

Satyarthi has said.

The government wants to amend a three-decade-old law which bans children under 14 from working in 18 hazardous occupations and 65 processes including mining, gem cutting, cement manufacture and hand-looms.

If passed by parliament in the coming weeks, the changes will outlaw child labour below 14 in all sectors, stiffen penalties for offenders and expand the age range covered to 15- to 18-year-olds.

But there are exceptions. Children who help their family or family businesses can work outside school hours and those in entertainment or sports can work provided it does not affect their education.

Also, children aged 15 to 18 will be barred from working in only three hazardous industries, said Mr Satyarthi, whose charity Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Childhood Movement) is credited with rescuing more than 80,000 enslaved children.

He said he welcomed the move to amend the child labour law but disagreed with the two exemptions.

“I definitely appreciate the government’s move to enhance the age of employment from 14 to 18 but these are two serious grey areas,” said Mr Satyarthi, speaking during an event hosted by the United Nations in the Indian capital New Delhi.

“Finally, the government has agreed to bring an amendment to the existing law – but what is more shocking is that this amendment is regressive, it is not progressive.”

Kailash Satyarthi delivers his UN lecture on child labour in New Delhi Picture: Facebook/Bachpan Bachao Andolan

There are 5.7 million Indian child workers between the ages of five and 17, out of 168 million globally, an International Labour Organization report said in February.

More than half are in agriculture, toiling in cotton, sugarcane and rice paddy fields, and over a quarter work in manufacturing – confined to poorly lit, barely ventilated rooms embroidering clothes, weaving carpets or making matchsticks.

Indian children also work in restaurants and hotels, washing dishes and chopping vegetables, or in middle-class homes, looking after other children or cleaning and scrubbing floors.

Satyarthi asked how the law would be implemented in a country where most enslaved children do not have birth certificates, and traffickers and employers pretend to be their uncles or other relatives.

“I have personally rescued thousands of children and most times in small-scale industries especially, the employers, traffickers and slave masters claim that they are uncles of the children,” said Mr Satyarthi, who was awarded the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize jointly with Pakistani schoolgirl Malala Yousefzai.

“Who is going to do a DNA test on them to check if they are related to the children?”

The government says the exemptions aim at striking a balance between education and India’s socio-economic reality, where children must go to school but also help their parents in occupations like agriculture and artisanship.

Learn more about how child labour affects education.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, covers humanitarian news, women’s rights, trafficking, corruption and climate change.

More news