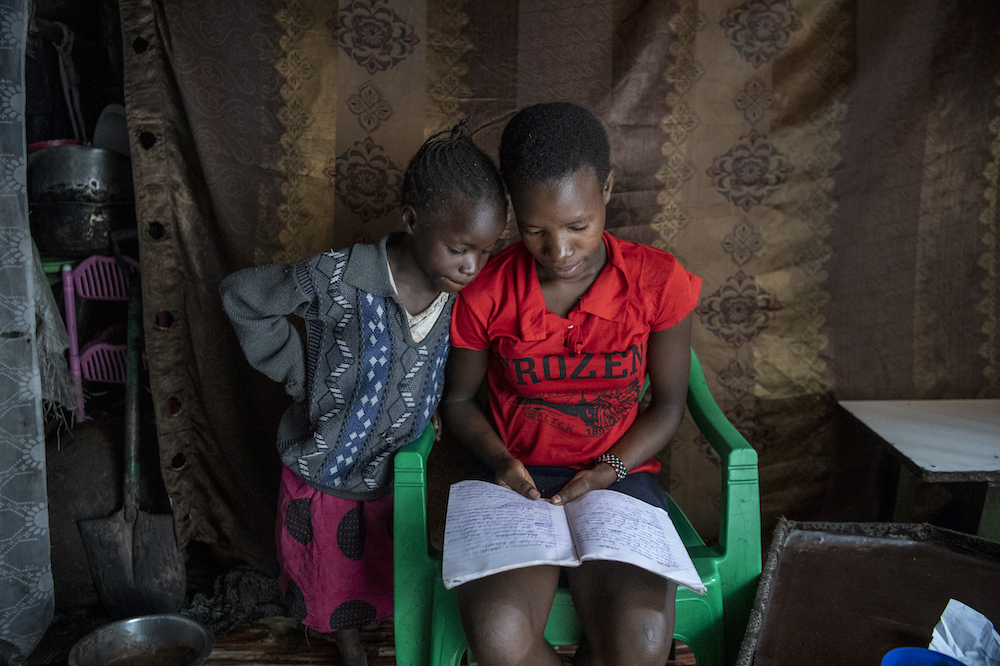

Rohingya crisis shines light on plight of the world’s stateless children

Barriers to education, Right to education

Three-quarters of the 10 million stateless people belong to minority groups - and many are denied education and other rights.

The plight of the Rohingya has focused attention on the issue of millions of stateless people around the world.

Not recognised by the authorities in Myanmar, more than 600,000 minority Muslim Rohingya have fled from violence in recent weeks over the border to Bangladesh.

For many children, getting some form of education in the refugee camps will be a new experience – 60% of Rohingya have never been to school.

Being stateless means not being recognised as a national by any country. It means life without an official identity and can result in generations of discrimination, extreme poverty and little or no education.

More than 75% of the world’s stateless people belong to minority groups, according to the report This Is Our Home by the United Nations refugee agency UNHCR. It called on governments to end the discriminatory practice by 2024.

They include the descendants of migrants, nomadic populations with links to two or more countries and groups that have experienced ongoing discrimination despite having lived for generations in the place that they consider to be home.

Stateless definition

The international legal definition of a stateless person is “a person who is not considered as a national by any State under the operation of its law”. In simple terms, this means that a stateless person does not have a nationality of any country. Some people are born stateless, but others become stateless.

Source: UNHCR

One such group is the 4000-strong Makonde of Kenya. Without citizenship or identification

documents such as IDs or birth

certificates, Makonde children were held

back from graduating from school or being

considered for scholarships.

Tina Eric, now 22, said: “One of

my teachers in school singled me out one

day and told the class that I was a Makonde.

‘Those are the ones that eat snakes,’ she

said.

“I was ridiculed after that. Even those

who I thought were my friends did not fully

accept me.”

After a long campaign, the Makonde became Kenya’s 43rd officially recognised tribe last year.

Another 30,000 stateless people in Thailand have acquired nationality since 2012 too, said the report.

“We are seeing reductions in Thailand, in central Asia, in Russia, in Western Africa. But the numbers are not nearly as substantial as they would need to be for us to end statelessness by 2024,” said Melanie Khanna, head of UNHCR’s statelessness section.

There are still about 3.2 million people in 75 countries who are known to be stateless, having been registered or counted by governments. But the estimated total is 10 million – including large populations in many countries including Indonesia, Ivory Coast, Lebanon and Democratic Republic of Congo.

“If you live in this world without a nationality, you are without an identity, you are without documentation, without the rights and entitlements that we take for granted … having a job, having education, knowing that your child belongs somewhere,” said Carol Batchelor, director of UNHCR’s division of international protection.

UNHCR says governments should give nationality to people born on their territory if they would otherwise be stateless – and facilitate naturalisation for longtime stateless residents.

For many, change will be too late. Like Sougraby Ibrahim, a woman from the Karana people of Madagascar – a Pakistani-Indian origins community of at least 20,000 people who languish in a stateless limbo.

Interviewed by UNHCR, she said: “I am 84 years old and have never attended school. I tried to go to school but they would turn me away saying, where is your birth certificate? But I did not have one.”

More news