Donor Scorecard: Just Beginning

Addressing inequality in donor funding for Early Childhood Development

Theirworld Donor Scorecard: Just Beginning

Key messages

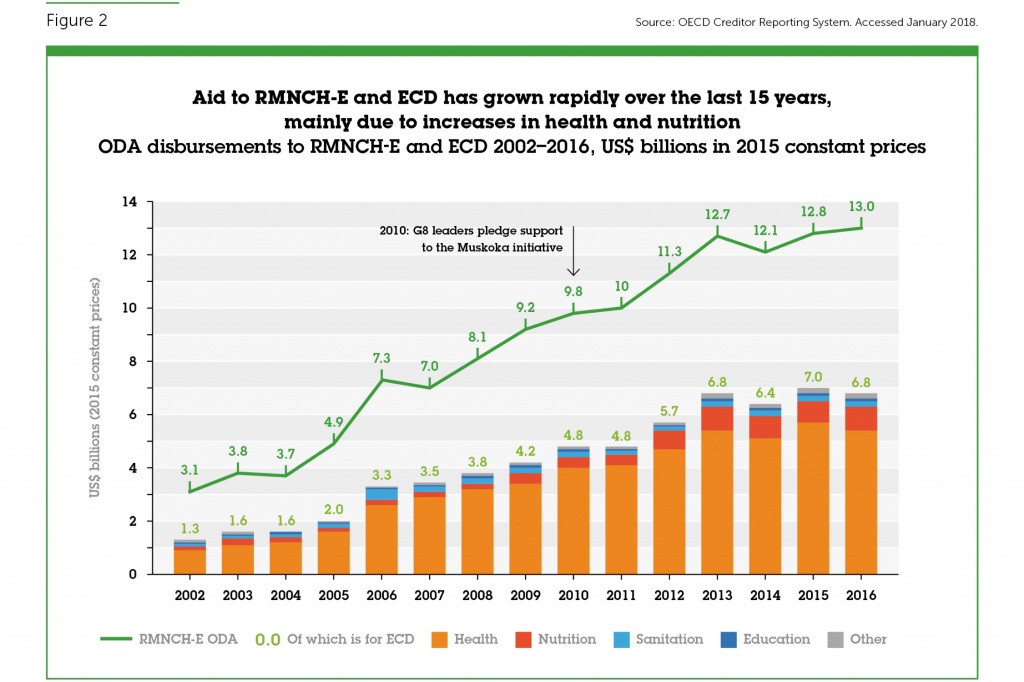

- Aid to Early Childhood Development (ECD) has increased in recent years – from U$1.3 billion in 2002 to US$6.8 billion in 2016. As a share of total Official Development Assistance (ODA), ODA for ECD has increased from 1.7% to 3.8% between 2002 and 2016.

- This increase in ECD financing has been almost completely due to large increases in the health and nutrition. These sectors alone accounted for 95% of the US$5.5 billion increase in ECD ODA between 2002 and 2016.

- Only 1% of all ECD aid funding goes to pre-primary education. Aid to pre-primary education declined as a relative share between 2002 and 2016 from 3% to 1% as levels of growth fell far short of that for the health and nutrition sector, and now forms only a very small proportion of ECD ODA.

- Only a small number of donors provide relatively sizeable funds to pre-primary education, making the sector vulnerable to changing donor priorities. In 2016 only three disbursed more than US$5 million globally to pre-primary education. In contrast 29 donors disbursed more than US$5 million to the health sector of ECD in 2016.

- Of the top 25 donors to ECD, 19 donors disbursed the majority of their ECD ODA to the health sector in 2016. In contrast 16 out of the top 25 donors to ECD give either nothing or the lowest share of their ECD ODA to pre-primary education.

1. Introduction

Early childhood development, defined for this paper as the period from birth to age five, is the time in a child’s life that is the most critical, with 90% of the brain having developed by the time a child reaches five years of age. In 2016, The Lancet reported that the process of brain development is largely affected by adequate attention being given to a child’s health, providing them with adequate nutrition, protecting them from harm and stressful environments, providing them with enough stimulation through play and giving adequate early learning opportunities (Black et al., 2016). It is widely recognised that a coordinated, integrated approach to early childhood development across these areas is vital for children to achieve their full potential.

Worldwide, however, many children continue to be deprived of these investments, which have lasting impacts both early on in a child’s life and later on into adulthood. The majority of these children are born into some of the world’s poorest countries and, increasingly, in regions affected or at risk of protracted conflict. Globally 43% of children aged five years or under are estimated to be at risk of poor development due to poverty and stunted growth; this is equivalent to 250 million to children globally (Black et al., 2016). These children are “failing to reach their potential in cognitivedevelopment because of poverty, poor health and nutrition, deficient care [and stimulating environments]” (Grantham-McGregor et al., 2007). Children from disadvantaged backgrounds, such as due to poverty, gender or disability, are the most likely to benefit from investment in early childhood development (Zubairi and Rose, 2017). The wide-spread evidence that the benefits far outweigh the costs should compel the international community to prioritise their resources towards those investments that would most benefit children during their early years (UNICEF, 2017a).

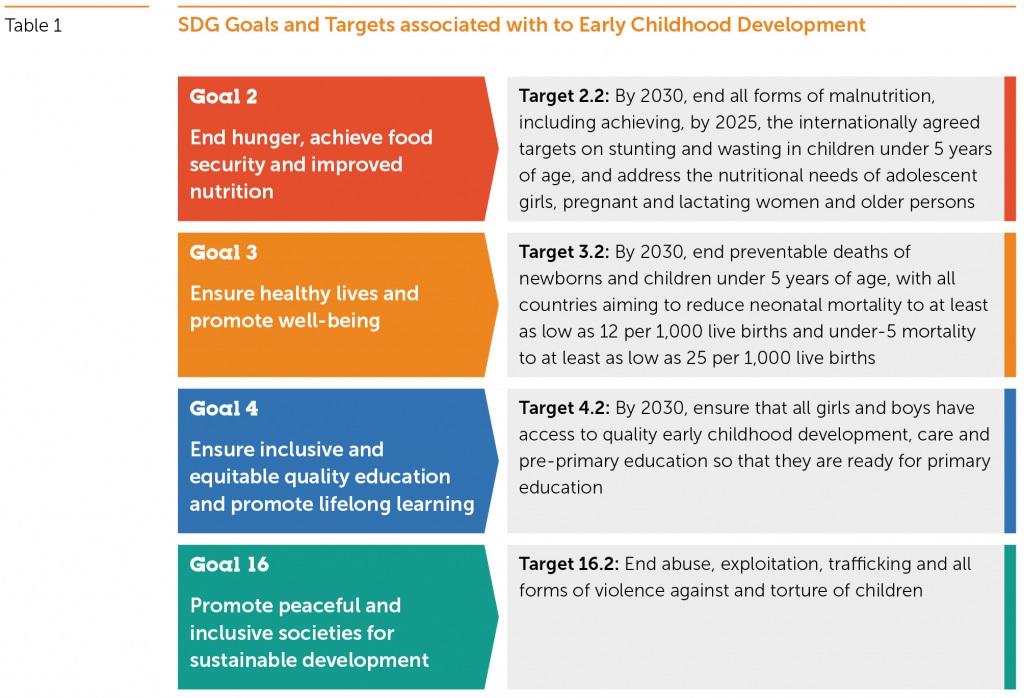

In recognition of the importance of early childhood development in leaving no one behind, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Agenda for 2030, includes specific targets on early childhood development across different goals.

Given this global commitment to early childhood development, it is vital to identify the extent to which investments are being made to realise the promise. Many donors recognise the evidence that shows the importance of investing in early childhood development, and the need for an integrated approach. We therefore focus in particular on donor funding to early childhood development, specifically with respect to areas for which resources can be tracked: health, nutrition, sanitation and pre-primary education. Other aspects of early childhood development such as play and protection are equally as important, and need to be integrated within an overall package of support. Unfortunately, however, it is not possible to identify donor resources allocated to these areas.

The scorecard tracks donor disbursements over the period 2002 to 2016 to interventions specific to children from 0 to 5 years. It finds that early childhood health and nutrition have benefited from a growth in resources over this period, while education and sanitation have declined in relative importance. This implies that donors have failed to fulfil a commitment to a coordinated, integrated approach. One reason for this is linked with high profile campaigns on early childhood health and nutrition, which appear to have been successful in mobilising donor resources. A potential reason for the focus of these campaigns could be that donors can see more immediate results from investing in health and nutrition, and are able to report more concretely on numbers vaccinated, lives saved and so on. While this is crucial, a failure to simultaneously invest sufficiently in education is likely to undermine the longer-term, less visible but equally important benefits associated with education.

The scorecard is organised as follows: Section 2 gives an overview of the sectoral areas commonly falling under the ECD sector. Section 3 presents an overview of aid disbursements to ECD between 2002 and 2016. Section 4 presents a donor scorecard in relation to their disbursements to the ECD sector, and specifically to pre-primary education within this. Section 5 provides the key conclusions, and Section 6 presents some of the key recommendations going forward, based on our findings.

This Scorecard builds on the findings of an earlier report on early childhood education prepared by the authors for Theirworld (Zubairi and Rose, 2017). It takes forward the findings in the previous report by identifying the extent to which pre-primary education is prioritised within early childhood development aid budgets. It uses the latest aid figures, based on 2016 data from OECD-CRS database, while the previous report used 2015 figures for the latest year.

2. Early Childhood Development: The areas of focus

In 2015, national governments along with the international community pledged support towards achieving 17 Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Early childhood development cuts across a number of the goals (Table 1). SDG targets in Nutrition (SDG 2.2.), Health (SDG 3.2) and Education (SDG 4.2) all commit to investments in the development of young children aged under the age of five, in order that they are able to achieve their full development potential.

In recognition that children living in conflict-affected environments are particularly vulnerable to being left behind, SDG Target 16.2, which focuses specifically on protection, also focuses specifically on ending all forms of violence against children. While the target does not focus on early childhood specifically, negative experiences, such as exposure to conflict or violence, have been shown to slow down and alter brain development, thereby affecting how a child grows and learns. In low and middle income countries with data it is estimated that 80% of children aged two to four years old are violently disciplined (UNICEF, 2017b). Added to this is the susceptibility to being born into conflict. In 2015 for instance it was estimated that 16 million babies were born into conflict. In Syria, for instance, one in three children aged under the age of six are estimated to have been born into and continue to live in a conflict-ridden environment (Theirworld, 2017). Yet despite this, a review by Theirworld in 2016 indicates that just 10 out of 38 2016 Humanitarian Response Plans, Flash Appeals and Refugee Response Plans made any mention of ECD, early childhood education or similar ECD terminology (Theirworld, 2016)

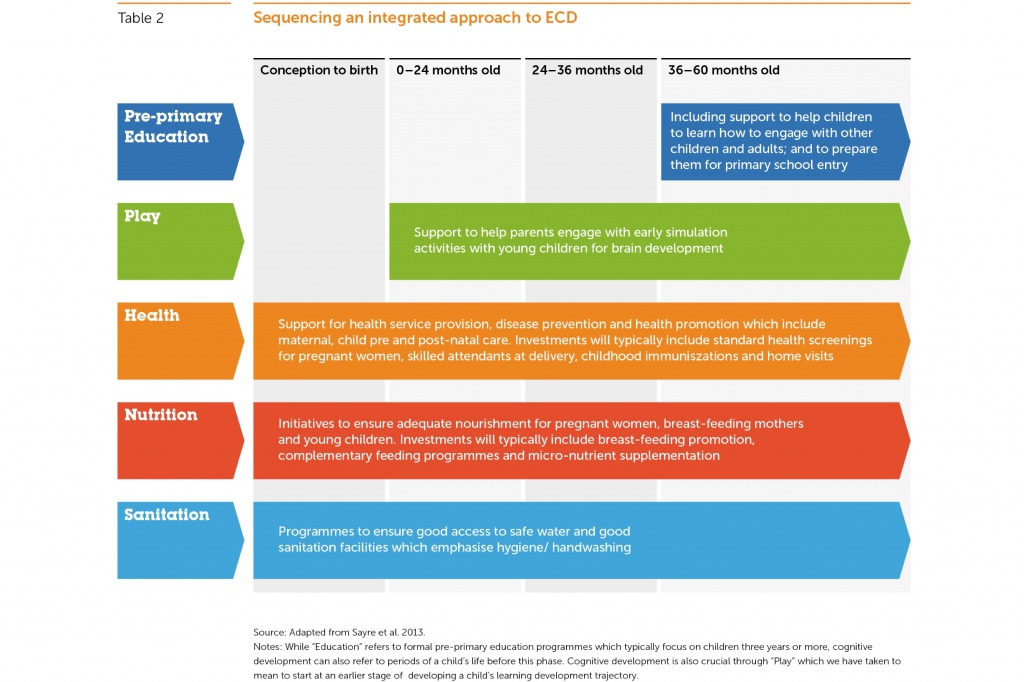

The definition of what period of a child’s life constitutes ECD can differ between stakeholders. For the purposes of this paper, we are particularly interested in investments relevant for children from birth until the age of five years old or the point before they enter primary education. The cross-sectoral focus of ECD indicates that in order for interventions to have the potential to mitigate many of the negative consequences of poverty, they need to be multi-dimensional in nature and dress four key domains: cognitive development, linguistic development, socio-economic development and physical well-being and growth (Naudeau et al., 2011). Addressing these domains requires a cross-sectoral approach which spans a range of sectors, including a need for investments for under-fives in the areas of play, education, health, nutrition, sanitation and social protection (Sayre et al., 2013):

Play: Play is an important part of a child’s early development, which helps their brains develop and for language and communication skills to grow. Play can be divided into five types, with each serving a broad purpose as far as development is concerned: these are physical play, play with objects, symbolic play, socio-dramatic play and games with rules (Whitebread, 2012). Approximately 90% of brain development occurs by age five with the frequency of play and communication in these early years of a child’s life having long-term consequences for a child’s learning, physical and mental health later on in life. One study in Jamaica, where health workers engaged with poor toddlers and supported mothers to encourage play, found these participants were more likely to do better in school and have better social skills than their counterparts who did not benefit from this intervention (Gertler and Heckman, 2014).

Education: Interventions in pre-primary education are among some of the most cost effective interventions governments and donors can make both for reducing inequalities and improving social and economic outcomes (Zubairi and Rose, 2017). One study simulated the impact on increasing pre-school enrolment. In 73 countries it found that if pre-primary school enrolment was increased to 25% or 50% in each low and middle income country, for every one dollar invested in quality pre-primary education there would be a benefit-to-cost ratio of between US$6.4 and US$17.6 (Engle et al., 2011). And yet, just 15% of 5-6 year olds in low income countries were enrolled in pre-primary education programmes, compared to 82% for 5-6 year olds in high income countries. Moreover, children from the poorest households are the least likely to enrol onto pre-primary education programmes (Zubairi and Rose, 2017). Yet, there is strong evidence that access to quality pre-primary education can give some of the most disadvantaged children the best start in life and later on in the education cycle. In Mozambique, rural children who had attended pre-school were 24% more likely to enrol in primary school and show improved cognitive abilities compared to their peers who had not enrolled (Martinez et al., 2012). The latest statistics indicate that pre-primary education continues to remain under-funded within total education spending. In 2016 donors disbursed just 0.7% of direct aid to education for spending on pre-primary education (OECD-DAC, 2017, in Zubairi and Rose, 2017).

Health: Investment in childhood interventions are deemed to be amongst some of the most cost-effective with respect to improving the number of ‘Disability Adjusted Life Years’ (DALYs), that is addressing the sum of years of productive life lost due to premature mortality and disability. Between 2008 and 2015 the share of DALYs bourne by children under the age of 15 declined from 41% to 28%. This reduction is largely attributed to a decline in deaths among children under the age of five years old (WHO, 2018a). Despite under-five mortality having decreased, 5.6 million children under the age of five are estimated to have died globally in 2016 (WHO, 2018b). Infectious diseases are the single most important cause of these deaths and they not only have an impact on child survival but also later growth and development (Woodhead, 2014). Studies of children aged five years or younger who are infected with HIV, for example, in low and middle income countries indicates they have much lower motor and mental development scores than their non-infected peers (Walker et al., 2011).

Nutrition: There are strong links between nutrition and cognitive, physical and emotional development. Globally, malnutrition disproportionately affects under-fives. Looking at the causes of under-fives deaths, undernutrition is estimated to contribute to a third of all global under-five deaths. It is estimated that globally, 155 million children younger than age five have stunted growth because of poor or inadequate nutrition and health care (UNICEF et al., 2017). Deficiencies in nutrition in early childhood can lead to a number of problems, including decreasing the immunity from infection and ability to recover from illness (UNICEF, 2017b). This can lead to problems for children developing in other areas; iron-deficiency anaemia is associated with poorer cognitive, motor and social-emotional development (Walker et al., 2011). A randomised trial in Guatemala showed benefits to reading comprehension and reasoning amongst 25-42 year olds for those who had nutritional supplements from birth to 24 months (Stein et al., 2008). For an investment of US$100 per child in developing countries, one study estimates that chronic under-nutrition could be reduced by 36% (Hoddinott et al., 2012).

Sanitation: Globally it is estimated that 3 in 10 people (2.1 billion) lack access to water facilities at home, while 6 in 10 people (4.5 billion) lack access to safe sanitation facilities. While this puts the health of all people at risk, children under the age of five years are particularly at risk from diseases such as diarrhoea which cause the deaths of 361,000 under the age of five years old each year (WHO and UNICEF, 2017). The impact of insanitary living conditions, which can lead to diarrhoea episodes and other diseases, can have a direct impact on schooling; studies in Brazil show positive correlations between diarrhoea episodes before age 2 and late school entry and school performance (Lorntz et al., 2006). Interventions which target improved water and sanitation have been found to be strongly associated with both improved growth and cognitive outcomes. In India for instance, the installation of pit latrines during the first year of a child’s life – as part of the Total Sanitation Campaign – was found to improve their literacy levels (Spears, 2013).

As Table 2 indicates, a holistic approach is required through various cross-sectoral interventions at different stages of a child’s life up until they turn age 5. ECD investments must be sequenced to ensure an integrated approach which meets all the needs a child has in relation to their cognitive and social development, health and nutrition needs. ECD investments must also be comprehensive in order to achieve the immediate and later desired economic and social benefits that can be achieved, as is well-documented through these various interventions.

Recent high-profile global initiatives indicate that some sectors within ECD have fared better in terms of the support they are given by the international community. In the lead-up to 2015, a number of global initiatives were put in place with the aim of putting countries back on track to reaching targets associated with the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). In particular MDG 3 – with a target to reduce the under-five mortality rate – was prioritised by donors given it appeared off-track in relation to the targets. These initiatives were also associated with the timing of the combined effects of the 2008/2009 global financial and food crisis, which saw a steep rise in food prices and sparked global concern for the world’s poorest populations. The visibility of food and nutrition security brought these into the spotlight of the global political agenda:

- An influential five-part Lancet series evidenced the irreversible effects of undernutrition in child development. The series criticised the failure of a “fragmented and dysfunctional” international nutrition system of made up of international and donor organisations, academia, civil society, and the private sector (Morris et al., 2008).

- In 2010 under the leadership of the then Canadian Prime Minister, G8 donors pledged commitment to the Muskoka Initiative on Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) which included a commitment to increasing international finance to this area. G8 donors committed to mobilise an additional US$5 billion in funding over five years on top of the US$4.1 billion which G8 donors were estimated to already contribute annually. In addition to the G8, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Republic of Korea and Switzerland – together with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the United Nations Foundation – committed to providing US$2.3 billion in resources (UN, 2010).

- Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) was initiated in 2010, formalised in 2011 and is still active. SUN is a global movement of 59 countries, global partners and more than 3,000 civil society organisations. The initiative has helped to mobilise greater support for investment in nutrition in order to improve the health outcomes and reduce mortality of the most vulnerable mothers and children with an emphasis on the first 1,000 days of a child’s life. While it does not act as a financial mechanism, its objective is to ensure that financial resources can be increased to 13 evidence-based nutrition interventions, and that these resources are coordinated and predictable in nature (Arnold and Beckmann, 2011).

- In April 2017, the Department for International Development (DFID) and the World Bank co-hosted the Spotlight on Nutrition: Unlocking Human Potential and Economic Growth event where global leaders came together to make the investment case for nutrition.

While the health and nutrition sectors of ECD have received national and international attention – including a scaling up of financial support – other areas of ECD have seen a conspicuous lack of attention both in terms of attention and financial support. Notably, despite the robust evidence documenting the multi-sectoral social and economic benefits of pre-primary education, this has failed to translate into sufficient attention at the global level. This might in part be due to the fact that the effects of lack of investment in pre-primary education are not as immediately visible as those in health and nutrition. This both means that it is more difficult to draw the attention of the global political economy, and that non-governmental organisations and other civil society organisations, that have been instrumental in bringing attention to crises associated with health and nutrition, have not been as active in doing so with respect to education. And, as we will show, even though donors may be increasingly emphasising the importance of early years of pre-primary schooling in their education strategies, this is not matched – in practice – by increased disbursements (see Section 4).

3. Tracking aid disbursement levels to ECD

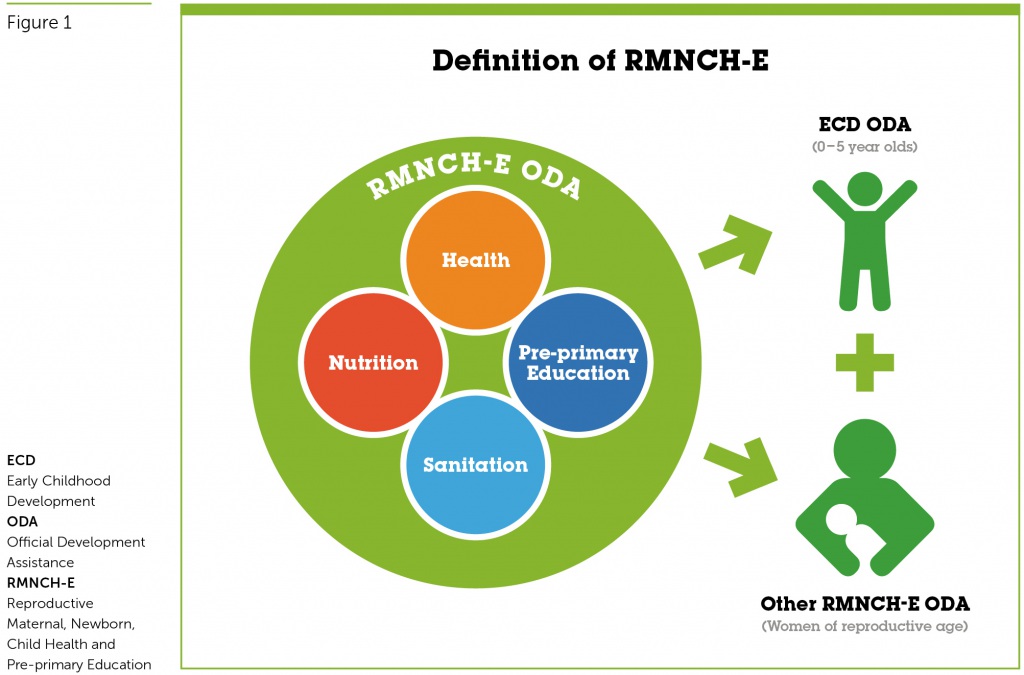

Recognising the well-documented benefits of ECD, this paper seeks to understand the extent to which donors are prioritising investment in this area through an analysis of their aid disbursements. The analysis for this paper has considered total aid disbursements to health, nutrition and sanitation sectors for Reproductive Maternal New-born and Child Health (RMNCH) as the starting point. It adds pre-school education to the areas conventionally included in RMNCH, given this is also identified as being vital for children aged under the age of five years with important benefits for their later development, reframing the focus to include education: RMNCH-E. The focus of RMNCH-E aid is inclusive of interventions for (a) children aged 0-5 years and (b) women of reproductive age, including those who are pregnant (Figure 1). This paper is particularly interested in monitoring the part of RMNCH-E aid that is specific for the 0-5 year age group, namely aid to ECD (see theirworld.org/5for5-methodology for details on the methodology used). Ideally, the analysis would include “play” and “protection” which are likely to be very relevant for the 0-5 years age-group. However, the OECD DAC-CRS database used for our analysis currently does not track aid for these sectors.

Between 2002 and 2016, donors have considerably increased their attention to RMCH-E overall. Over this period, total ODA disbursements increased from US$73 billion to US$181 billion representing an increase of 148% in real terms. RMNCH-E aid increased from US$3.1 to US$13.0 billion over this period, representing increase in 311% in real terms. As a share of total ODA, the amount disbursed for RMNCH-E has increased from 4.3% to 7.2% between 2002 and 2016.

Within RMNCH-E, the share allocated to ECD (that is, not including aid to support women of reproductive age) has grown over the same period (Figure 2). ECD ODA grew from US$1.3 to US$6.8 billion between 2002 and 2016. This represents an increase of 440% in real terms. As a share of total RMNCH-E ODA, the share going to ECD has increased from 40% to 52% between 2002 and 2016, showing the increased attention given by donors to the early years.

The growth in ODA disbursements for ECD, is however, imbalanced with respect to its sub-components. It is largely attributed to the health (the largest sub-sector) and nutrition sectors (second largest sub-sector), which saw a particularly large increase from 2010/2011 onward. This is around the same time donors made financial commitments towards the initiatives highlighted in Section 2.

By contrast, education and sanitation comprises a very small component of ECD, and their relative importance has not kept pace with the overall increase in attention to funding of early years interventions. Of the US$5.5 billion increase in ECD between 2002 and 2016, 81% of the increase was attributable to disbursements in the health sector and 14% to the nutrition sector; sanitation and pre-primary education only contributed 2% and 1% to the increase, respectively. As a result, the share of education within the composition of ECD fell from 3% in 2002 to 1% in 2016. By contrast, the share to health within the composition of ECD increased from 74% to 80% over the same period.

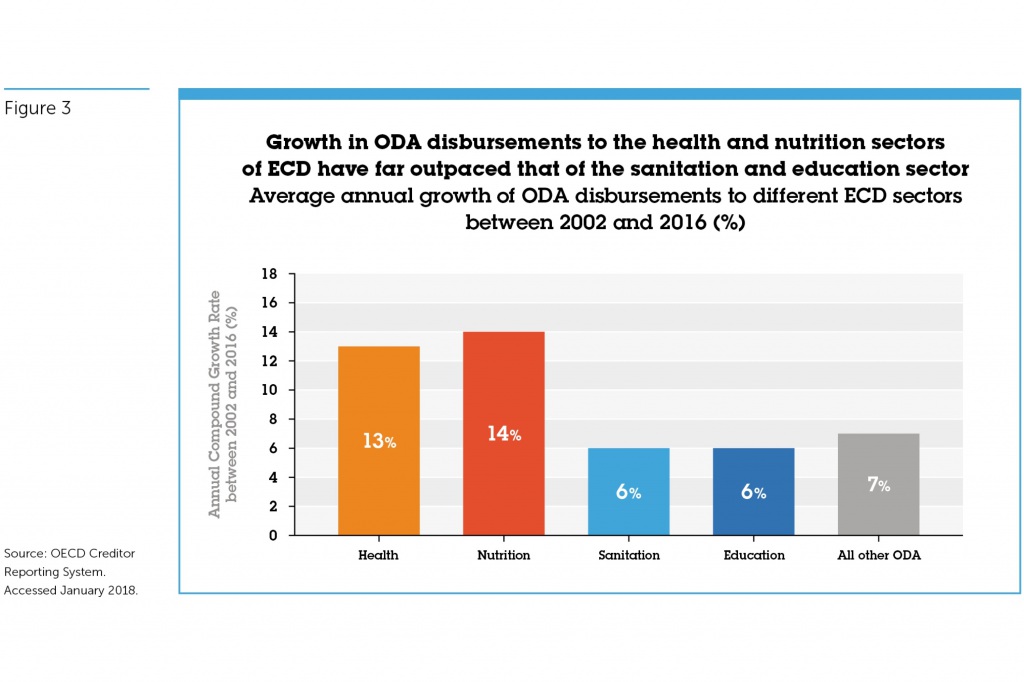

Put another way, between 2002 and 2016, ODA disbursed to pre-primary education and sanitation increased, on average, by 6% per annum (Figure 3). By contrast, other aspects of ECD increased more rapidly than the overall increase in aid, with health and nutrition sectors of ECD witnessing a 13% and 14% increase on average per annum over the same period.

The low levels of ODA and slow growth of aid to pre-primary education and sanitation is further perpetuated by the small number of donors disbursing to these sectors. Of the 93 bilateral and multilateral donors, just over a quarter (24 donors) disbursed any ODA to pre-primary education in 2016. Of these 24 donors just three (Canada, Korea and the World Bank) disbursed US$5 million or more in 2016 (Figure 4A). For sanitation the equivalent was nine donors (Figure 4B). This is considerably lower than for other sectors. In the health sector, 29 donors disbursed funds for ECD-related activities (Figure 4C) and for nutrition 15 donors did so (Figure 4D). The relatively small number of donors in education and sanitation makes these sectors highly vulnerable to changing donor priorities.

Comparing the average amount that all donors who submitted something to each particular ECD sector, the levels disbursed to sanitation and pre-primary education are far lower than that for health and nutrition. On average across all the 24 donors that disbursed aid to pre-primary education in 2016, the average amount was US$3.4 million. This is similar to sanitation where, on average, the 36 donors disbursing aid to sanitation in 2016 disbursed US$4.3 million each. For basic nutrition, the 31 donors disbursing aid averaged approximately US$28.3 million each. For health, of the 57 disbursing aid, the amount averaged US$69.1 million each.

4. Donor Scorecard tracking commitment to ECD

We now put the spotlight on the top 25 donors to ECD aid in 2016. The section identifies the extent to which these 25 donors are prioritising pre-primary education within their ECD aid disbursements, and how much their spending needs to grow in order to fill financing gaps.

Donor commitment to ECD is ranked in terms of the amount they allocate to ECD as a proportion of their total aid spending (Table 3a). Some of the top 25 donors to ECD according to this measure are ones who are the largest donors overall.[i] Among the top ten ECD donors are the United States, the United Kingdom, the World Bank and EU Institutions – all of whom also disbursed amongst the largest volumes of total ODA in 2016. The top ten also includes some smaller donors to aid overall, such as UNICEF and Ireland.

Comparing aid spending by sub-sectors of ECD in 2016, 19 out of the 25 donors disburse the majority of their ECD ODA to the health sector (Table 3b). Conversely, 16 out of the top 25 donors to ECD give either nothing or the lowest amounts of their ECD ODA to pre-primary education. Notably, the United States and the Netherlands, which are the second and third largest donors to ECD (and the first and twelfth largest aid donors overall), give no ODA to pre-primary education. Notably, the United States and the Netherlands, which are the second and third largest donors to ECD (and the first and twelfth largest aid donors overall), do not report any ODA to pre-primary education. Of the remaining nine donors, just one – Finland – disburses the largest share of its ECD aid to pre-primary education. And only two other donors, in addition to Finland, allocate more than 10% of their ECD spending to pre-primary education: the other two donors are Belgium and Korea.

Overall volumes of spending to pre-primary education by bilateral donors are extremely low: bilateral donors disbursed just US$38 million in 2016. The largest bilateral donors to pre-primary education in volume terms in 2016 were Canada, Germany, Korea and the United Arab Emirates. The overwhelming majority of pre-primary education ODA disbursed by multilateral donors comes from the World Bank (US$34 million in 2016), followed by UNICEF, which disbursed just US$4 million in 2016.

For some of the top 10 donors to ECD, relative to their overall aid spending, the amount they allocate to pre-primary education relative to their spending on ECD overall is extremely small. UNICEF, which spends the[p1] largest proportion of its aid on ECD, disburses less than 1% of ECD ODA to pre-primary education. Similarly, the United Kingdom, which is the fourth largest donor overall and sixth largest with respect to spending on ECD relative to its overall aid, spends less than 1% of ECD on pre-primary education (Table 3b).

The Global Partnership for Education (GPE) is not included in the tables as it does not report its aid disbursements to the OECD Creditor Reporting System.[ii] It is, however, a relatively significant donor to pre-primary education compared with other donors with respect to the share of its total ODA to pre-primary education: of the US$4.5 billion in total funding that GPE has disbursed to education since 2002, 4% was for pre-primary education – equivalent to approximately US$180 million.[iii] Comparing this to the amount each of the top 25 donors disbursed in total to pre-primary education over 2002-2016 this is high: GPE ranks as the second largest donor in volume terms after the World Bank over this period. However, as a fund that is purely for education, we argue that the GPE is failing to adequately prioritise its budget towards the ECD component of education. Comparing GPE with the estimated shares that global health funds disburse to the ECD component of health, GPE’s commitment to early childhood spending is extremely low: the share of funds disbursed by GAVI and the GFTAM to the ECD component of health, for instance, is estimated to be the equivalent of 89% and 27% respectively.

In 2017, in line with the recommendations made by the Education Commission that a rising share of donors’ national wealth should be gradually increase towards 0.7% earmarked for international development assistance of which 15% should be for education by 2030[p2] , Theirworld recommended that 10% of total education ODA should be allocated to pre-primary education (Education Commission, 2016; Zubairi and Rose, 2017). If donors were to meet this target,[iv] by 2030 total resources for pre-primary would reach US$5.8 billion. This would be a 71-fold increase from current levels (US$82 million). If such a target were to be achieved, levels disbursed to pre-primary education would need to increase on average by 36% every year between now and 2030 (Table 3c).

Table 3c considers the fair share that each donor should contribute to reach the 2030 target for pre-primary education. Based on this analysis, the United States, Germany, Japan and the United Kingdom would need to fill a large share of 2030 pre-primary education target. The United States alone would be expected to fill a quarter of the financing gap on account of it being the largest economy in volume terms and that it disburses the majority of its ODA in bilateral ODA. Between the current levels it disbursed to pre-primary education in 2016, and the 2030 target of US$1.5 billion, levels disbursed by the United States would need to grow by 23% every year between 2016 and 2030. Given its low starting point, aid to pre-primary education would need to grow the fastest in the United Kingdom to reach the target: by 73% per year, on average.

With respect to multilateral agencies, the share of the target expected to be met by the EU Institutions, World Bank and UNICEF is also large. EU Institutions are expected to fill close to 10% of the target, while the World Bank is expected to fill 8% of the target. The increase in the amount the EU would need to disburse to pre-primary education in order to meet the target is 45% every year between now and 2030, which is one of the highest for any of the donors.

[i] In 2016, Turkey was the eighth largest donor overall, primarily due to its humanitarian spending. None of this spending is allocated to ECD, however. As such, it does not appear on the tables.

[ii] To avoid double-counting, we have not included GPE in the tables but instead have considered their prioritisation of ECD as a share of their total disbursements to education since 2002 as information on their spending is only available cumulatively.

[iii] Correspondence with the Global Partnership for Education Secretariat, May 2017.

[iv] While the 0.7% target has been applied to most donors reporting to the DAC Creditor Reporting System, for the USA and the non-DAC reporting donors this paper has assumed a 0.5% target by 2030.

Donor Scorecard Tables

5. Conclusions

Adequate investments to ECD are vital to equip every child with the right start in life and help mitigate the adverse consequences of poverty, conflict and vulnerability that a child may be born into, through sequencing support in key areas crucial to child development. The SDGs present a clear call for action to support ECD initiatives through nutrition, health, education and protection initiatives to ensure that leaving no-one behind can be a realisable achievement by 2030.

As the analysis from this report illustrates, donors have increased their investments towards the early childhood years over the last 15 years. However, the growth in ODA resources is imbalanced. Pre-primary education has seen some of the slowest rates of growth from the already low levels of ODA disbursed at the beginning of the millennia, while health and nutrition have seen greater global attention which has translated into greater donor disbursements.

Without sustained investment in all areas crucial to achieving effective ECD outcomes, the long-term benefits of ECD interventions will not be achieved. Donors must invest in the area of ECD in a sequenced and holistic manner. As such, pre-primary education needs to receive far greater attention than is currently the case.

6. Recommendations

The promotion of ECD within the SDG Agenda across multiple sectors requires strong donor commitment in supporting children under the age of five: Within Goal 2 (Hunger), Goal 3 (Health), Goal 4 (Education) and Goal 16 (Protection), the importance of improving outcomes for children aged 0-5 years is clearly outlined. Without effect targeting of this group, many of the targets will remain unmet. With the strong evidence base that addressing inequalities early in life can mitigate the lack of opportunities later in life, donors must prioritise their resources towards achieving all of the early year SDG targets.

Increase the share of total ODA investments earmarked for ECD: Between 2002 and 2016, donors doubled the share of total ODA disbursed for ECD from 1.7% to 3.8%. Despite high-profile commitments by donors to supporting children aged 0-5 years, there is a need for renewed commitment and greater transparency on donors spending given the widespread evidence of the short and long-term benefits of investing early.

Ensure donors take a balanced approach to investing in ECD: Financial commitment by the international community is needed to ensure comprehensive coverage of ECD to ensure a scaling up of resources to currently under-funded sectors of ECD, namely education and sanitation. A commitment, similar to the Muskoka Commitment of 2010 and the Scaling Up Nutrition (SUN) initiative, must be made in support of these under-funded areas of ECD. In addition, play and protection are vital components of ECD, but remain invisible in donor spending. As a first step, information on donor commitments in these areas is needed. In anticipation that their invisibility is likely to be a signal of their under-funding, an Initiative to support under-funded areas of ECD should include these.

Commit to providing additional support to the under-funded areas of ECD – particularly pre-primary education – to better track additional resources to the sector against donor pledges: With pre-primary education poorly prioritised within donors’ education, ECD and overall ODA budgets, current levels of ODA to pre-primary education must fulfil the pledge that 0.7% of national wealth be spent on aid ad 15% earmarked for the education sector by 2030, in line with the recommendation from the International Commission on Financing Global Education. In line with the Theirworld 2017 recommendation, a minimum of 10% of ODA disbursed for education should be allocated to pre-primary education.

Improve the division of labour between donors to ensure that certain sectors within ECD are not being left neglected: In 2016, just three donors disbursed US$5 million or more to pre-primary education leaving the sector considerably more vulnerable to changing donor priorities than the health part of ECD which included 29 donors disbursing at least US$5 million in 2016. To adhere to one of the core principles of aid effectiveness, there must be better coordination between donors to guarantee no ECD sector is being left ‘orphaned’ and that there an acceptable number of donors supporting it with adequate financial resources.

Establish the International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd) to mobilise, front-load and better target resources to pre-primary education. Current ODA levels to pre-primary education are poorly targeted with the majority of donors disbursing funds too thinly to a large number of countries. The Education Commission proposal of an IFFEd mechanism will be crucial in helping to mobilise and front-load resources from public and private funders for the education sector and targeting these towards investing in pre-primary education in those countries most in need of resources.

Education Cannot Wait should provide clear targets for pre-primary education: In May 2016, Education Cannot Wait: A Fund for Education in Emergencies was launched as an innovative new global platform to address the education needs of children affected by humanitarian emergencies. While data on spending on early childhood development, and early childhood education within this, is not available for conflict-affected countries specifically, a review of 38 active humanitarian and refugee/ regional response plans and flash appeals for 2016 reveal that just 10 made any mention of early childhood development, early childhood education or similar ECD terminology, suggesting that spending is likely to be extremely low. And yet the importance of early childhood development, incorporating education and protection, is vital in these settings. As such, Education Cannot Wait needs to prioritise its spending towards early childhood education.

Provide better and transparent information on the targeted financial interventions to ECD by sector: Of the 28 World Bank SABER Early Childhood Development country reports reviewed for the 2017 Theirworld report on financing pre-primary education, only six countries have begun to report partly to these information gaps. Better information is needed to effectively monitor the total resources available for ECD and, within this, what is being spent on specific interventions/ sectors. To achieve greater accountability, donors must assist various stakeholders in better reporting to make information more transparent in order that total resources to various parts of ECD system can be more effectively monitored.

Appendices and further resources

Appendix 1: Donor Profiles

Appendix 2: Methodology

For more in depth data please refer to our tables here on Google Sheets or download in PDF format.

Download the Scorecard

Next resource