Millions of children under five still die each year from preventable causes

Childcare, Early childhood development, Safe pregnancy and birth

Progress has saved millions of young children - but treatable diseases and poor conditions are still contributing to the 15,000 deaths per day.

Thousands of babies are still dying daily from preventable causes – and pneumonia, diarrhea, malaria and malnutrition are killing millions of under-fives in the developing world.

Progress is being made on young children’s health, with the under-five mortality rate almost cut in half since 2000. But sadly millions will still never reach their fifth birthday.

In fact, children in sub-Saharan Africa are 10 times more likely to die before the age of five than children in high-income countries.

A staggering 5.6 million children under five year last year – 15,000 per day – according to the World Health Organization (WHO). And many of these deaths could have been prevented.

These shocking figures show the importance of good health practices in the birth process and the care of young children.

Nurturing care includes access to health care plus clean water and sanitation – starting with ante- and postnatal visits for pregnant women, a skilled birth attendant and vaccinations.

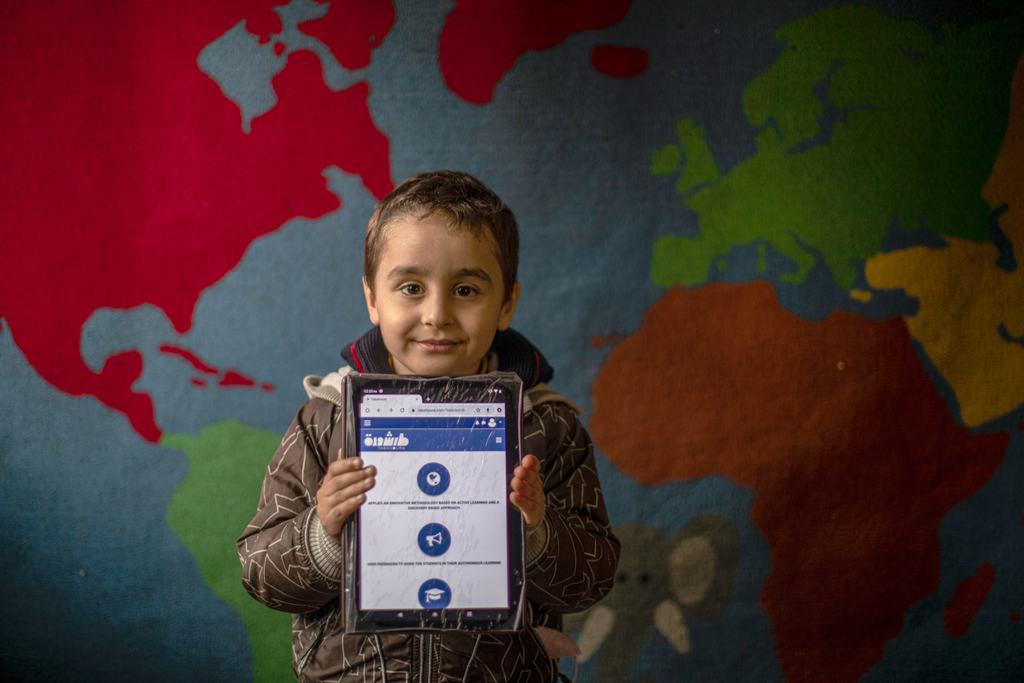

Health care is one of the five key areas of Theirworld’s #5for5 campaign, which calls on world leaders to invest in early childhood development and pre-primary education.

While newborns are at the greatest rink, infants who survive into toddlerhood are then at risk from malnutrition, diarrhea and other treatable diseases.

Vaccinations, better sanitation and clean water – things the developed world takes for granted – would all save lives. Pneumonia, diarrhea and malaria accounted for almost one-third of deaths among under-fives globally.

In Yemen, UNICEF reported today that suspected cholera and acute watery diarrhea have affected over one million people – with children under five accounting for a quarter of all cases.

The Born Into War report added: “Women who became pregnant during the first 1000 days of war have given birth in deplorable conditions, without access to proper medical care, clean water and or a hygienic environment for delivery.

“Many mothers are malnourished and ill themselves, increasing their risk of dying or giving birth to premature and malnourished babies who do not make it beyond the first month of their life.”

Diptheria can be another major killer. In Bangladesh, WHO, UNICEF and partners are working with the health ministry to vaccinate more than 475,000 children in Rohingya refugee camps, temporary settlements and surrounding areas.

Almost 150,000 of these being vaccinated are aged from six weeks to seven years.

“All efforts are being made to stop further spread of diphtheria,” said Dr Bardan Jung Rana, WHO Representative to Bangladesh. “The vaccination of children in the Rohingya camps and nearby areas demonstrates the health sector’s commitment to protecting people, particularly children, against deadly diseases.”

A child’s risk of dying is highest in the first 28 days of life – with 2.6 million deaths in 2016, or 46% of all deaths among under-fives.

Improving the quality of antenatal care, care at the time of childbirth, and postnatal care for mothers and their newborns are all essential to prevent these deaths, says WHO.

But there is good news amidst the gloomy statistics.

Newborn deaths

Two regions account for almost four-fifths of newborn deaths – Southern Asia with 39% and sub-Saharan Africa with 38%.

Half of all newborn deaths happen in five countries – India (24%), Pakistan (10%), Nigeria (9%), Democratic Republic of Congo (4%), Ethiopia (3%).

A UNICEF spokesman said: “The remarkable progress in improving child survival since 2000 has saved the lives of 50 million children under the age of five – children who would have died had under-five mortality remained at the same level as in 2000 in each country.”

However, more needs to be done – particularly on diseases such as diarrhea. It’s a condition people in every country can identify with.

But just think what it would be like if you couldn’t get access to clean water and proper sanitation when you were ill. You would just keep getting gradually worse.

This is the problem for young children especially. Around 500,000 children under the age of five died from diarrhea-related illnesses in 2015, according to a report in the Lancet Infectious Diseases journal. The number of deaths fell by 34% between 2005 and 2015 after concerted efforts to improve water and sanitation worldwide.

“Diarrheal diseases disproportionately affect young children,” said Dr Ali Mokdad of the University of Washington’s Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the report’s lead author.

“Despite some promising reductions in mortality, the devastating impact of these diseases cannot be overlooked. Immediate and sustained actions must be taken to help low-income countries address this problem by increasing healthcare access and the use of oral rehydration solutions.”

Malnutrition also poses a massive threat to under-fives.

UNICEF said: “Nearly half of all deaths in children under five are attributable to undernutrition, translating into the loss of about three million young lives a year.”

The country with the highest rate of under-five mortality was Somalia, with 133 deaths for every 1000 live births. By comparison, the United Kingdom has a rate of four deaths.

“It is unconscionable that in 2017 pregnancy and child birth are still life-threatening conditions for women and that 7000 newborns die daily,” Tim Evans, senior director of health, nutrition and population at the World Bank Group, told the Guardian.

“The best measure of success for universal health coverage is that every mother should not only be able to access healthcare easily – but that it should be quality, affordable care that will ensure a healthy and productive life for her children and family.”

More news

MyBestStart programme gives young girls the education they deserve