Kindergarten lottery means children miss out on early education in Mongolia

Childcare, Early childhood development

Government-funded classes have space for only half of children aged two to five in the capital Ulaanbaatar - so an online ballot is determining who gets in.

Mongolia’s baby boom is pushing its schools to breaking point, with desperate parents facing the stark choice of relying on a lottery system or paying for pricey private classes in capital Ulaanbaatar.

Spots in coveted government-funded kindergartens, for children aged two to five, are determined by an online ballot.

Those who miss out risk being left out of the early years education system altogether – unless they can afford a fee-paying option.

Sukhbaatariin Boldbaatar and his wife cannot afford a private nursery for their two-year-old son – he is looking for work, while she cares for their one-month-old infant at home.

“We thought we would win and we were going to buy his school material,” Boldbaatar said.

“But we received a text message saying he was not selected. At that moment I thought, ‘how could they treat a two-year-old based on luck’.”

The city’s publicly-funded kindergartens have space for just half of the 146,000 children between the ages of two and five who live there, according to the municipal education department.

Experts blame the shortage on bad government policy and poor long-term planning. The majority of Mongolia’s state-run schools were built during the Soviet era and relatively few new facilities have been added since the country became democratic in 1990.

Those who do get in face crammed classrooms and overburdened teachers as resources are stretched.

Fed up with having to work in jammed classes for low pay, public school teachers went on strike on September 21 and September 26.

The 122nd kindergarten of Bayanzurkh has 660 students, double its capacity.

“We had to adapt to working with over 60 pupils (per classroom),” said teacher Tsergiin Bayalag.

“This double workload doesn’t just affect teachers. The cooks must make twice as much food. I want the government to pay a good enough salary for teachers,” he added.

The overcrowding also poses health risks, with germs and the flu being passed around, leaving hospitals struggling to attend to a high number of sick children.

Those with a high enough income no longer even bother with the ballot as the private options offer better learning environments.

There were enough warning signs, but not enough measures taken Batkhuyagiin Batjargal, executive director of Mongolian Education Alliance

Poorer families, who do not secure a place in the public system, have little choice but to keep their children at home until age six, as kindergarten is not compulsory.

Mongolia’s birth rate has soared from 18.4 babies per 1000 population in 2006 to 25.4 per 1000 last year, according to the national statistics office. There were some 49,000 births a decade ago, compared to around 80,000 last year.

A possible explanation is that a generation from a previous baby boom in the 1980s has reached reproductive age.

In the capital, where half of the country’s population lives, internal migration of jobless herders from rural areas has added to the problem.

Batkhuyagiin Batjargal, executive director of the Mongolian Education Alliance NGO, said the crisis is the result of bad public policy.

“There were enough warning signs, but not enough measures taken,” Batjargal said.

Birth rates soared in the Year of the Golden Pig in 2007, as Mongolians believe that year brings wealth, but little was done in anticipation of the extra demands on resources as those babies grew up.

The government is building schools in the ger, or slum, districts of Ulaanbaatar – but the country’s debt problems have restricted spending.

Secondary schools are also packed but there is no lottery to enrol as the constitution guarantees free education to all children from the age of six.

Lkhagvasurengiin Oyunchimeg, who has 44 students in her class at School Number 65, can’t find empty classrooms to give extra classes to children who lag behind.

“Sometimes we work with those kids in the corridors,” Oyunchimeg said. “But the corridor is not a proper study area and they get easily distracted.”

More news

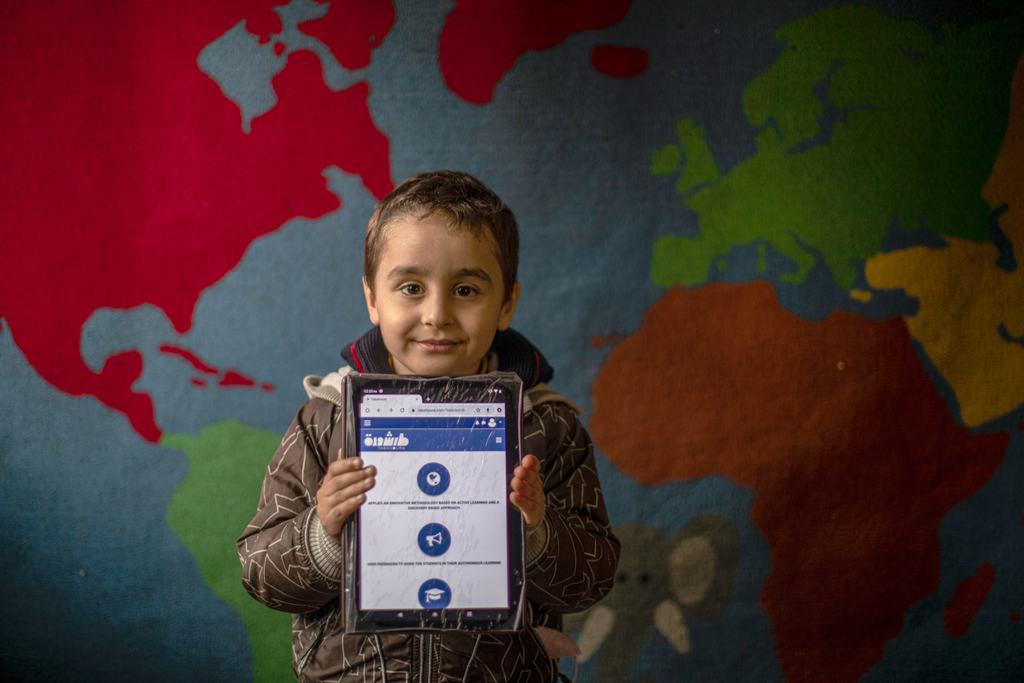

MyBestStart programme gives young girls the education they deserve