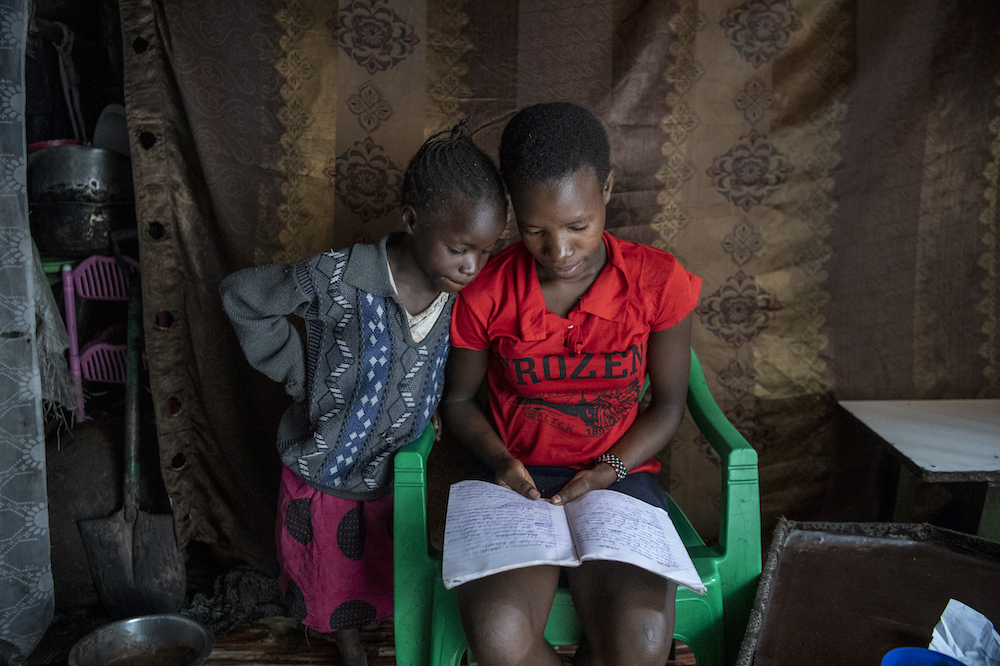

Small payments help to reduce child trafficking and get children into school

Child labour, Child trafficking, Right to education

A pilot project in Benin has had a huge impact on the number of children being sold by their poverty-stricken families to work in quarries and agriculture.

Giving poor families just $6 a month has significantly reduced child trafficking in parts of the West African country of Benin where there is a longstanding practice of exploiting children for labour in fields and mines, the World Bank said.

At least 40,000 children a year are estimated to be victims of trafficking in Benin, according to the United Nations children’s agency UNICEF, although the latest data is a decade old.

The phenomenon is widespread and growing, with many parents selling their children into labour because they cannot support them and have no other means of income, said Marie-Consolee Mukangendo, UNICEF’s national head of child protection.

But families in some of the poorest villages have stopped sending their children away since they were given 3500 CFA francs ($6) a month for two years under a pilot programme funded by the World Bank, the project’s manager said.

We reluctantly sent our children to Nigeria to work in order to have something to eat. Today, the money I receive at the end of every month allows me to comfortably send my children to school instead of making them work. Yvette Adangnonhou, beneficiary of the programme

The central commune of Za-Kpota is known as a base for trafficking to neighbouring Nigeria, where children are sent to work in stone quarries, said Germain Ouin-Ouro, who manages community development projects for the government.

“After two years we saw the rate of trafficking totally dropped. Some families were even able to bring their children home,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

The programme benefited about 1100 families in Za-Kpota. Most of them had sent children to work abroad, Ouin-Ouro said.

The team did not collect data on the number of victims but learned through interviews during a follow-up visit that the practice had nearly stopped and that families were sending their children to school with the extra funds, he said.

In addition to the cash transfers, farmers were paid to build roads and dig wells during the agricultural lean season.

Some pooled their earnings to create small businesses, Ouin-Ouro said. Families will likely need three more years of support to ensure change is lasting, he added.

“I’m convinced that cash transfers to the poorest can play a key role in prevention,” said UNICEF’s Mukangendo, adding that more awareness about the risks to children is also needed.

Teaching children vocational skills at home has also helped reduce trafficking to Nigeria in the past, said an official at Nigeria’s anti-trafficking agency, NAPTIP.

“If there is an intervention to change community dynamics, it would be good. Otherwise, giving money as a handout is not sustainable,” Godwin Morka told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

More news

“Education can help to end child trafficking”