Brands urged to use profits to keep Indian children out of work and in school

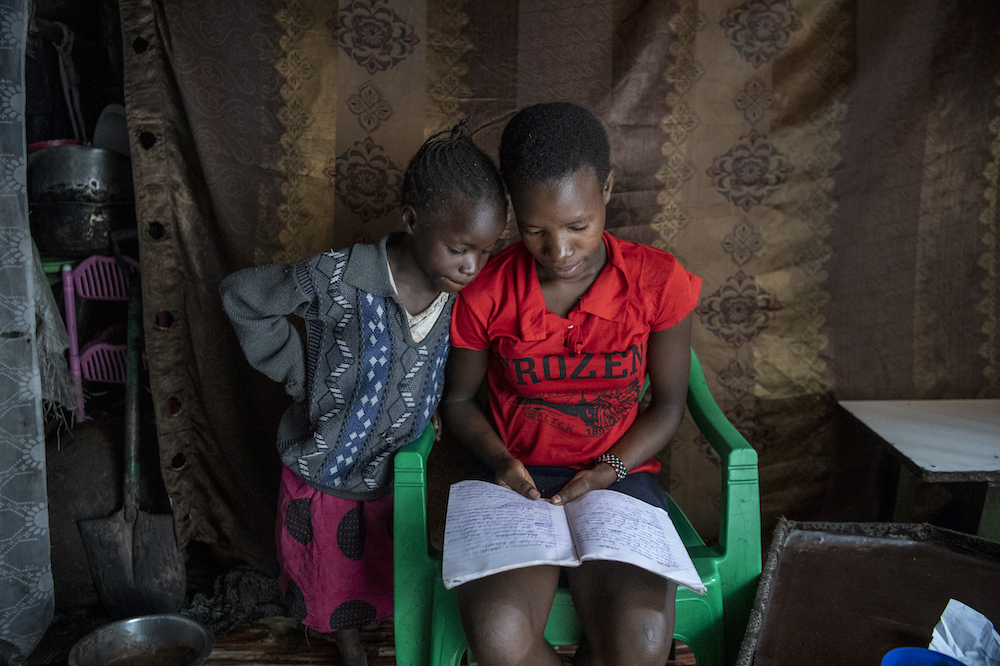

Right to education

In a country with more than 5.7 million child labourers, companies should help to ensure children living in "labour hotspots" finish their education, says a coalition of charities.

Brands sourcing garments, shoes, leather and natural stones from India must help create and sustain child labour-free zones by mapping their supply chains and working with communities to boost school enrolment, activists said today.

The Stop Child Labour Coalition of charities recently launched a campaign with guidelines for companies to help ensure that children living in “labour hotspots” finish school.

“Brands must take responsibility and share their profits to help keep children in school,” said A. Aloysius, founder of Social Awareness and Voluntary Education, a charity in the south Indian textile hub of Tirupur that is part of the coalition.

From ensuring fair wages for adult labourers to working with village councils on enrolment drives and improving access to education, the campaign aims to make “potential child labourers work only in schools”.

According to the International Labour Organization, more than half of India’s estimated 5.7 million child workers between the ages of five and 17 toil on farms.

Over a quarter are in manufacturing on tasks such as embroidering clothes, weaving carpets and making matchsticks.

Children also work in restaurants and hotels, and as domestic workers.

A 2017 UNICEF report, based on Indian census data, says the proportion of child workers in the five to nine age group jumped to 25% in 2011 from 15% in 2001.

Many companies do not engage children in their own facilities but have no checks when they subcontract production to smaller factories or home workers, where the prevalence of child labour increases drastically, campaigners say.

“Child labour has often moved further down the supply chain, making monitoring more difficult,” said Venkat Reddy of the M V Foundation, a charity in the coalition.

The coalition’s guidelines urge the private sector, civil society and government to work together on interventions for child labour-free zones.

After applying these guidelines, two communities in Tirupur with some 20,000 households in December were declared child labour-free.

“It was the first time that small garment manufacturers in the area agreed to work with us on the issue,” Aloysius said.

The guidelines draw from successful interventions in the cotton fields of Andhra Pradesh, stone quarries of Rajasthan and shoemaking workshops of Agra.

“Like a quality check section, we want brands to add a social responsibility unit in the factories,” Reddy said.

“Supply chains run deep and brands know that. They don’t have to build schools, just be part of programmes to keep children in school.”

More news

Five things you need to know this week about global education