How early care centres could help to stop rural Chinese children dropping out of school

Barriers to education, Childcare, Early childhood development, Right to education

A pilot project of 50 early childhood development centres could help to set children on the path to education.

Every day after lunch, Qu Yexiu used to potter around her house in northwest China doing housework and looking after her two-year-old grandson.

Now, every day after lunch, Qu and her grandson visit the newly-opened early childhood development centre in their village of Huangchuan in the mountains of Shaanxi province, where he can play with other toddlers.

“Things are better now that we have this village centre,” said Qu, 56. She looks after her two grandchildren while their parents work and live in nearby Anhui province. The other grandchild attends a preschool.

“My grandson has other kids to play with and I can chat to the other grandparents.”

Early childhood development centres like the one in Huangchuan may be the answer to one of China’s biggest challenges – reducing the number of children who drop out of school in rural areas.

Children in rural areas, where around half of the population lives, have far lower cognitive and social skills compared to their urban counterparts, setting them on a path of dropping out of school before they can even say their own name.

This is the biggest problem that China faces that no one knows about. This is an invisible problem. Scott Rozelle, co-director of the Rural Education Action Program

Poor education was not such a problem for previous generations of Chinese who spent their lives on the farm or in factories but it could now have far-reaching consequences.

The government wants to push the country up the value chain, so the world’s second-largest economy needs a higher-skilled labour force if it wants to transition to a higher-value economy.

“This is the biggest problem that China faces that no one knows about. This is an invisible problem,” said Scott Rozelle, co-director of the Rural Education Action Program (REAP), a research and policy organisation based at Stanford University in California, which partners with Chinese universities.

“China has the lowest levels of human capital (out of all the middle income countries in the world today). China is lower than South Africa, lower than Turkey. We think that’s related to when they were babies, they didn’t develop well,” Rozelle said.

China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission is working with economists like Rozelle and his colleagues to provide early childhood development opportunities to babies and toddlers in rural China.

76% of China’s labour force did not attend high school, based on figures from the country’s last census in 2010, according to an academic paper co-authored by the Asian Development Bank and published last year in the China Quarterly, an academic journal.

The gap between rural and urban China is also big. Only 8% of rural Chinese in the labour force in 2010 had attended any high school, compared to 37% of urban Chinese, according to the China Quarterly article.

One factor slowing down a toddler’s development is the absence of their parents, education experts say.

Millions of rural Chinese parents migrate to cities to live full-time because they can earn much more than they could by staying in their home villages.

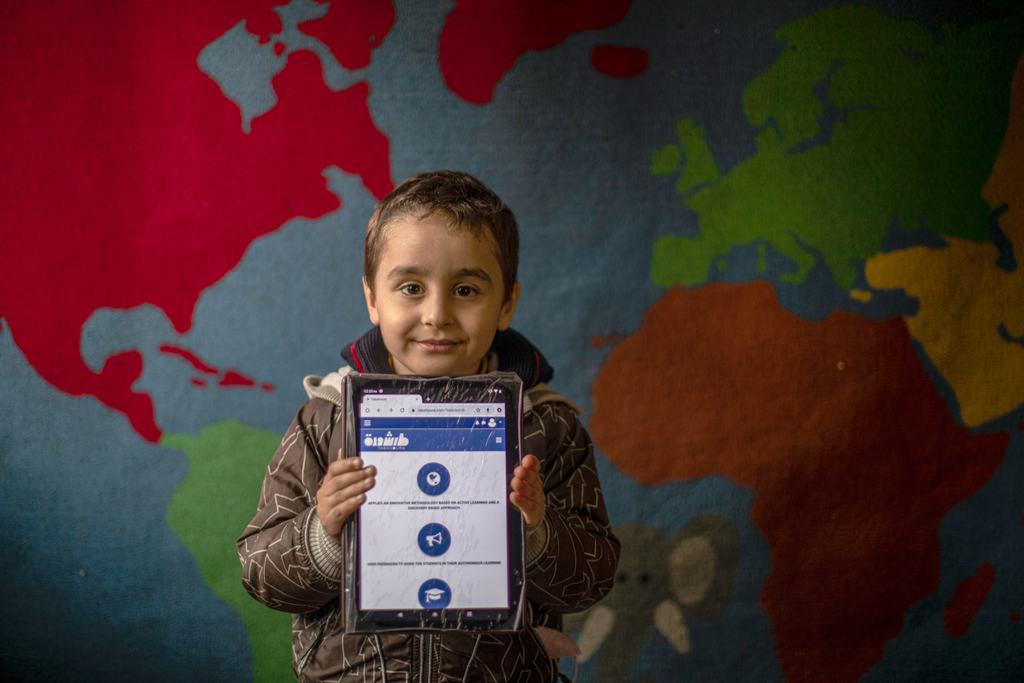

That’s where early development centres in China could help. Under the programme, there are 50 pilot centres in villages and towns in rural China where children from six months to three years old can experience books, play and interact with other children.

REAP thinks 300,000 centres are needed across China and the most appropriate entity to head this up would be the government.

Cai Jianhua, a government official at China’s National Health and Family Planning Commission, wants the government to allocate 0.1% of its GDP – 70 billion yuan ($10.5 billion) – to roll out these centres across the country.

Cai says the government has not made a funding commitment. But it has stepped up investment in its youngest citizens in recent years with, among other things, free health checks and immunisations for babies.

More news