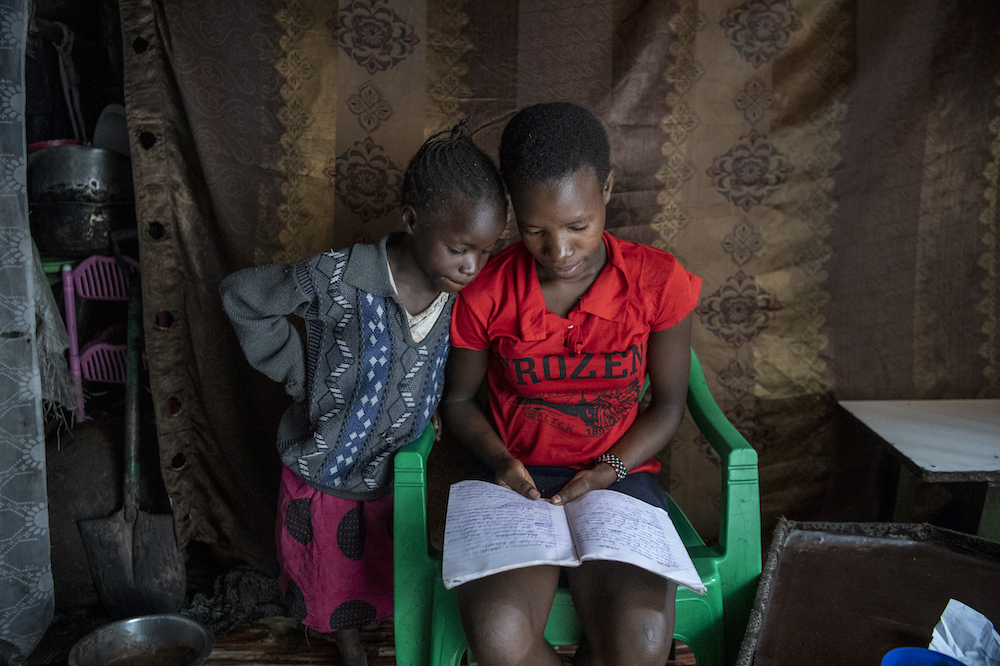

Countries move to end child labour – but globally the picture is still bleak

Child labour, Child trafficking, Right to education

More than 150 million children are still forced to work - often depriving them of education, causing them stress and putting them in danger.

The United Nations wants to eradicate child labour by 2025. But with more than 150 million children under the age of 18 working, that’s going to be a massive task.

Some countries and global campaigners are trying to push through measures that will at least make a dent in the appalling statistics.

Nepal’s government and the owners of the country’s 1100 brick-making factories – which employ almost 300,000 children – agreed a few days ago to end the practice of children working in brick kilns.

In Egypt, the government has launched a national plan to end child labour by the UN’s target date. Campaigners are calling on the European Union to bring in rules to tackle child labour in the cocoa and coffee sectors.

And a campaign to encourage people to report cases of child labour has been running this year in Colombia.

“Child labour is a factor of inequality because a child who works does not have the same opportunities as those who are studying,” said Karen Abudinen, head of the Colombian child protection agency ICBF.

But these are pockets or progress and resistance in an otherwise pretty bleak picture. Child labour is a violation of children’s rights – working can harm them mentally or physically and expose them to hazardous situations. Many child labourers never go to school or drop out because they have to work.

Across the world, 152 million children aged five to 17 are victims of forced labour, according to the International Labour Organization (ILO). They toil in homes, mines, fields and factories, carry heavy loads, work long hours and suffer exposure to pesticides and other toxic substances.

One of the worst forms is when children are trafficked and forced to work.

Senami, a 13-year-old girl, was purchased in Benin and taken to Gabon to work as a domestic servant and then a roadside peanut seller.

She told AFP news agency she worked for a “wicked” woman in the capital Libreville who made her “do everything” and “beat me with slippers and a stick”.

Gabon is only one of nine West African nations – alongside Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Mali, Nigeria and Togo – where the UN says the centuries-old exploitation of child labour remains entrenched.

“Trafficked children can work from 10 to 20 hours a day, carry heavy loads, operate dangerous tools and lack adequate food or drink,” a UNICEF report said.

The vast majority of child labourers work in farming and their numbers are rising – from 98 million in 2012 to 108 million in 2017, according to a statement from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

“After years of steady decline, child labour in agriculture has started to rise again in recent years, driven in part by an increase in conflicts and climate-induced disasters,” it said.

Almost half of all child labour happens in Africa, where about 72 million children work. The prevalence of child labour is 77% higher in countries affected by conflict.

More and more Syrian children living in Lebanon are having to work as poverty intensifies among the country’s one million or so refugees.

The proportion of Syrian child refugees working in Lebanon has risen to 7% from 4% in late 2016, according to research by the Danish Refugee Council in June.

Mounir, 13, had to make money for his family by selling sweets in the city of Tripoli until 11pm each day. He now works 10-hour days at a barber shop.

His favourite subject at school in Syria was mathematics and he dreams of going back to learn how to read and write.

“I want to become a mechanic. I like fixing things like motors,” he said.

As a problem, child labour poses immense challenges for us. We all need to join hands to put an end to this problem Mohamed Saafan, Egyptian labour minister

In Nepal, the agreement to end children working in the brick kilns was signed on July 30. The government said it was also working towards ending child labour completely by 2028.

“Now that the agreement to end child labour in brick factories has been signed and will be implemented immediately, the government will focus on ending child labour in other sectors as well, like transportation and hotels,” said Mahesh Prasad Dahal, secretary at the Ministry of Labour, Employment and Social Security.

The Egyptian government’s plan to end child labour by 2025 will involve civil society and the business community.

“As a problem, child labour poses immense challenges for us. We all need to join hands to put an end to this problem,” said Labour Minister Mohamed Saafan when the programme was launched last month.

A 2017 national survey found that 1.6 million children aged from 12 to 17 are working – but campaigners believe the figure could be much higher. Most work in rural areas and 63% are in agriculture.

The plea to the EU to tackle child labour in the cocoa and coffee industries also came last month at a European Parliament hearing on the issue.

More than two million children work on cocoa plantations in the Ivory Coast and Ghana – and Europe is a major importer of the products.

In 2012 the European Parliament adopted a resolution that urged the European Commission to explore legislative measures to tackle child labour in cocoa. But no law was ever drafted.

More news

“Education can help to end child trafficking”