“I have been doing this job for 20 years because I love it and I love children”

Early childhood development, Health and nutrition, Safe pregnancy and birth

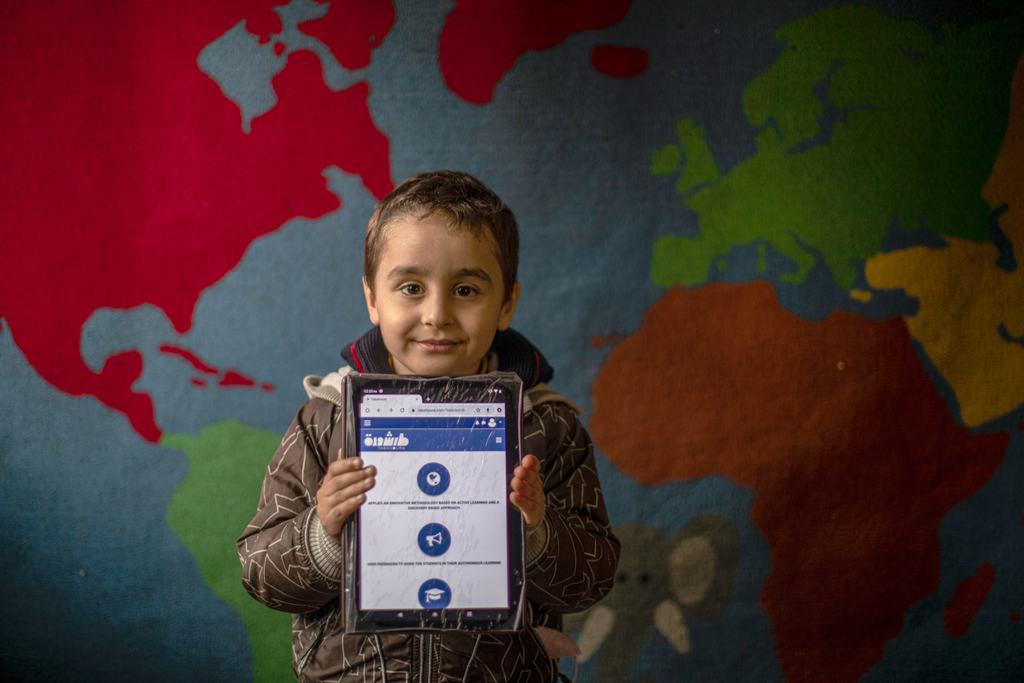

This week Theirworld is looking at the early childhood development workforce who help children under the age of five to grow and flourish - today we talk to health workers.

Every child in the world deserves to fulfil their potential. That means giving them quality care and nurturing in the crucial first few years of their life.

By the time a child reaches five years old, 90% of their brain has already developed. During that time, they need access to quality care, including the five vital areas of nutrition, health, learning, play and protection.

That’s why Theirworld’s #5for5 campaign is calling on leaders to help make early childhood development a top priority.

The early childhood development workforce has a key role to play. In a special series this week, Theirworld talks to teachers, health workers and day care owners and managers about the challenges and the joys of helping to give children the best start in life.

Evelyne Adhiambo Okell, a community health volunteer

I do this job at the Baba Dogo early childhood development centre because I love children.

My routine at the clinic in Nairobi, Kenya, involves collecting the children’s medical cards, sifting through them to identify those who have been vaccinated and those yet to be vaccinated, and at the same time write new cards for the children under two weeks who have not been given names as yet.

After the names are written, the mother is then sent to the Voluntary Counselling and Testing Centre for HIV testing.

When she returns the child is then weighed and at the same time the mother is educated on breastfeeding, nutrition and how to play with their infant child.

The majority of the children we get here are from age zero to five years and come from all walks of life – both the wealthy and underprivileged. They get vaccinations and immunisations,

We give priority to couples who have come together, then fathers who have brought their children – we also teach them how to change diapers.

We also educate the parents on the importance of taking children to baby care or day cares – and tell them which ones we have visited and prefer.

The clinic is easily accessible and is normally full of people during immunisation days, which are Monday and Fridays, and also because the services here are free of charge.

We teach all the mothers the importance of talking to their children in their womb and when they are born. Evelyne Adhiambo Okell, community health worker

Many of the children who come here have diarrhoea and vomiting. We were brought a television set by Kenyatta University, which has aided in reducing the cases through the cleanliness videos we showcase and teach.

I have undergone lots of training and train others as well – training such as how to live a good life if you are HIV positive.

We have many who visit the clinic and are HIV positive. They were in denial but now through proper education they have come out in large numbers and the stigma is dying down.

We also have fewer cases of children born being positive because we start teaching the mothers while they are pregnant.

We teach all the mothers the importance of talking to their children in their womb and when they are born. We discourage the carrying of children who can walk but let them play with the balls and toys that we have around.

My work is hard and needs commitment and drive because no one is forcing you to do it. We were many but others left because this job has no pay. You will sit here from morning to evening and not take anything home.

This is a calling and I have been doing it for 20 years. This is the only job I do.

Alice Nderitu, an occupational therapist

My work at Little Rock inclusive early childhood development centre in Kenya entails dealing with special children with developmental challenges and functionality.

Most of the children here have cerebral palsy, autism and Down syndrome. Others have minor congenital deformities and learning disabilities as well as epilepsy.

Joseph was brought here a year ago and is suffering from bilateral spasticity – his legs cannot extend. He was taken for surgery and the knee tendons were released to enable them to stretch.

He is going through recovery and we are training him how to be independent. He is 12 years old and, according to my observation, he has been with this condition since birth.

In the last year we have seen improvement in terms of mobility. He can wheel himself from one class to another which he couldn’t before.

His confidence has also improved. He was malnourished, didn’t have strength to move about. Now he can sit upright, can write in class and is very sharp.

Physical disabilities can affect children mentally too. They see other people playing which they can’t do, they see others looking at them walking around, which may stigmatise them.

So part of the occupational therapy involves talking to them, telling them yes you can, that disability is not inability. You can live and work like any other child.

We also talk to their parents and give them home programmes. Therapy is a combined effort and we give them activities they can do with their children.

We have a maximum of 12 children per day. Currently we have 92 children with special disabilities, a big number. Each child takes 45 minutes of individual therapy.

Our biggest challenge is lack of cooperation from the parents and the children, especially when you tell the parents not to feed a particular diet

And most of the parents who bring the children are women because the men seem to be in denial and leave the child to the mothers.

More news

MyBestStart programme gives young girls the education they deserve