From Ebola to coronavirus: education must not be forgotten in a health crisis

Education in emergencies, Health and nutrition, The Global Business Coalition for Education (GBC-Education)

The challenge faced during the 2014 epidemic in West Africa of ensuring that children don’t fall between the cracks now confronts the whole world.

In the midst of global upheaval, a reason for rejoicing this week went almost unnoticed. After five years, Sierra Leone finally overturned a ban on pregnant girls attending school.

Thousands were barred from returning to classrooms or taking exams after the total shutdown of the school system during the deadly Ebola outbreak of 2014-16 led to a dramatic increase in teenage pregnancies and sexual assaults.

When the schools reopened many months later, Sierra Leone’s government claimed that letting pregnant girls continue their studies was bad for their health and would encourage other students to get pregnant. That led to years of campaigning by education and human rights activists to have the ban overturned.

When that happened on March 30, Marta Colomer – Amnesty International’s Acting Deputy Regional Director for West and Central Africa – said: “We have cause to celebrate as thousands of pregnant girls across Sierra Leone will be allowed back into classes nationwide when schools reopen after Covid-19.”

The global coronavirus pandemic and the more concentrated Ebola virus epidemic – which killed more than 11,000 people – are very different situations. But there are similarities in the way in which education and the safety of children is affected.

A teacher uses a digital thermometer to check the temperature of a student when schools reopened after the Ebola crisis (UN Photo)

In both health crises – as in many humanitarian emergencies – education was hit quickly and hit hard. Ebola forced five million children out of school for up to nine months in the West African nations of Sierra Leone, Guinea and Liberia. Many never went back.

The current pandemic has disrupted the education of 90% of the world’s students, from pre-primary to university. There are fears that – as with the West Africa crisis – many young people will fall through the cracks, disappear from the school systems and become long-term victims of the emergency.

“While we hope that children and students will soon be able to go back to school, let’s make sure that global education is not forgotten during the crisis or in its aftermath,” said Theirworld President Justin van Fleet.

In 2014, with millions of children affected by nationwide school closures, a major report was produced by two Theirworld initiatives – the Global Business Coalition for Education and A World at School. It proposed a three-pronged approach for dealing with education during and after the Ebola crisis – ideas that laid the groundwork for much of what followed.

The report said there were urgent steps for governments and the international community to take:

- Emergency education until schools reopen

- Safe schools to reopen as quickly and as responsibly as possible

- Investment in sustainable schools and planning for emergencies

(UN Photo)

Moses Owen Browne Jr was a young activist at the time, a Global Youth Ambassador for A World at School. He remembers well the devastating effects of Ebola on his home country of Liberia.

“More than 5,000 people died and 6,000 children were orphaned,” said Moses. “The country was brought to its knees and the schools were shut down for many months.”

When classrooms did reopen, the virus had left long-lasting consequences.

“After Liberia was declared Ebola-free, children returned to school in joy and excitement – but couldn’t hold back their tears due to the many deaths of women and children,” said Moses, who is now Liberia’s Permanent Representative to the International Maritime Organization.

“Some parents were not able to send their children back to school due to the consequences of the outbreak on their livelihoods and communities. Some couldn’t even afford a day’s meal, let alone pay high tuition fees.

“Ebola caused emotional and physical damage to survivors and communities alike. The Liberian economy is still struggling to recover today – and here we are with coronavirus and back to zero.”

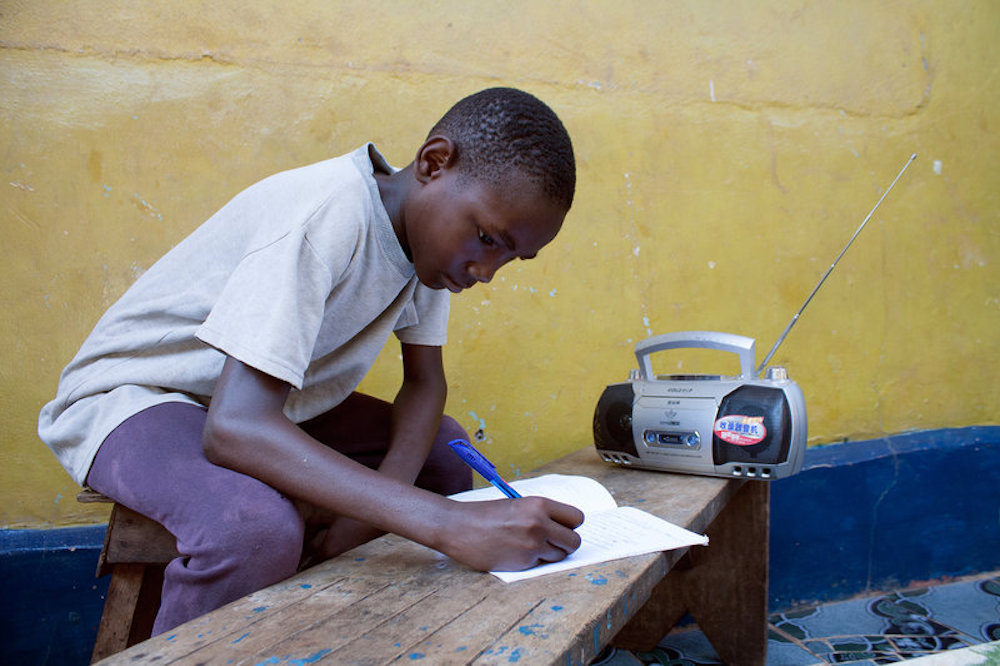

(UNICEF / Ongoro)

When Ebola caused the closure of schools in 2014, there were fears that unless they reopened quickly, millions of children would be at risk of dropping out permanently, getting pregnant or ending up in child labour – all significant risks for children whose education is disrupted by humanitarian crises. Schools provide safe spaces where they can receive education and psychosocial support for their trauma.

The three countries worst hit by Ebola already had large out-of-school populations. At the time, only 61% of children completed primary school in Guinea, 65% in Liberia and 72% in Sierra Leone.

The report from the Global Business Coalition and A World at School contained 10 key recommendations. On the immediate response, it urged using remote learning tools such as TV and the internet, and paying staff during school closures, including those in private schools.

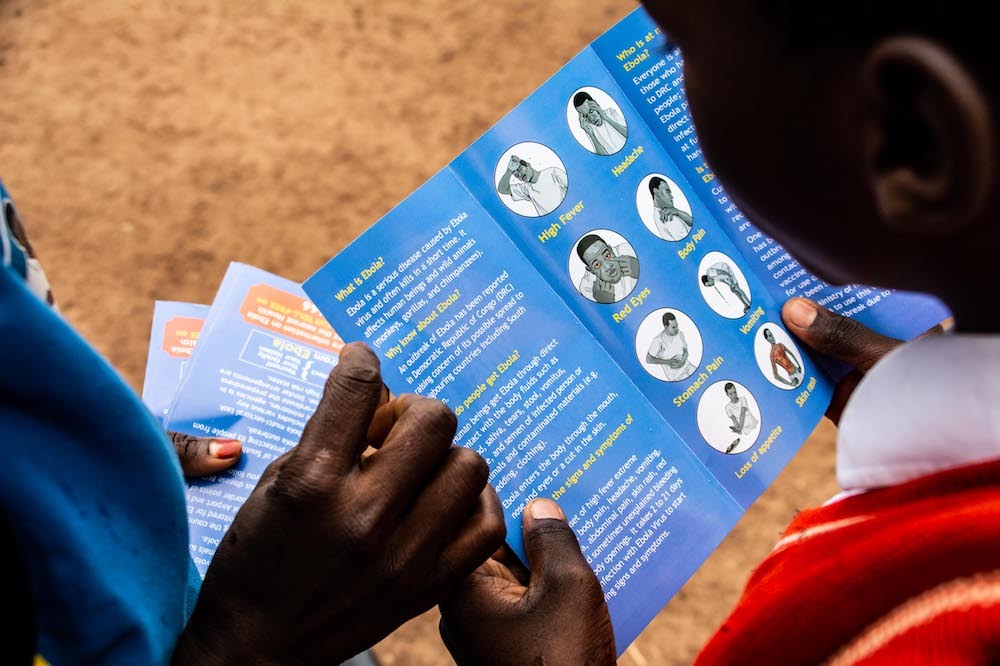

On the safe reopening of schools, it said schools should be cleaned and disinfected publicly to allay parents’ fears. Teachers should conduct temperature checks and monitor signs of infection among students. On sustainable safe schools, education authorities should implement preventative public health programmes on basic measures such as hand-washing, vaccinations and sanitation practices. It also called for contingency plans for future emergencies.

Theirworld’s Global Youth Ambassadors campaigned for governments to include education in their emergency responses. The Liberian government adopted the report, while Sierra Leone replicated its recommendations.

To avoid contamination with the Ebola virus, children learned to wash their hands thoroughly (World Bank)

When Liberia’s schools reopened, students lined up to have their temperatures taken and their hands washed in chlorine before they were allowed to go into classrooms. Now the country is facing up to a new health threat.

“The education system was picking up,” said Browne. “We have been experiencing increases in enrolment and high-level performance in the national exams at least for the past two years.

“But with Covid-19, the education system will need great help to rebuild and support to encourage children to go back to school after the outbreak.”

The current outbreak will leave many countries facing difficult decisions about how to spread their resources to ensure education is not left out of the response and recovery.

In a blog on the issue, Theirworld’s van Fleet had this message: “When faced with these choices, it is imperative to remember that today’s children are tomorrow’s nurses, epidemiologists, doctors, researchers and public health experts. We need to continue investing in learning today so that the world can be better prepared to solve future epidemics and crises tomorrow.”

More news