Education is a lure for families and children who flee violence in Central America

Right to education

Growing numbers of child migrants are being caught and sent home - but gang violence and stigma means they struggle to reintegrate into schools.

Many families who flee from gang violence and poverty in Central America are trying to get their children a better education and a brighter future.

Lack of educational opportunities is cited as a factor in people attempting to cross into Mexico and the United States, according to a report by UNICEF.

But growing numbers of migrants are being deported back to their own countries – and the stigma of being caught and sent home means children find it hard to reintegrate into schools.

The report by the United Nations children’s agency shows that tens of thousands of children, either traveling alone or with their families from El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala, attempt to pass through Mexico to the USA every year.

They are often left deeply in debt or targeted by gangs once they return to their home countries, said the report Uprooted in Central America and Mexico.

“Millions of children in the region are victims of poverty, indifference, violence, forced migration and the fear of deportation,” said María Cristina Perceval, UNICEF Regional Director for Latin America and the Caribbean.

“In many cases, children who are sent back to their countries of origin have no home to return to, end up deep in debt or are targeted by gangs. Being returned to impossible situations makes it more likely that they will migrate again.”

In Honduras, Henry Javier Menjivar Ramirez – principal at a school in Potrerillos – said: “The community, the population who is of working age, they have migrated – most of them because they don’t have a job. We used to have 860 students and currently we only have 219.”

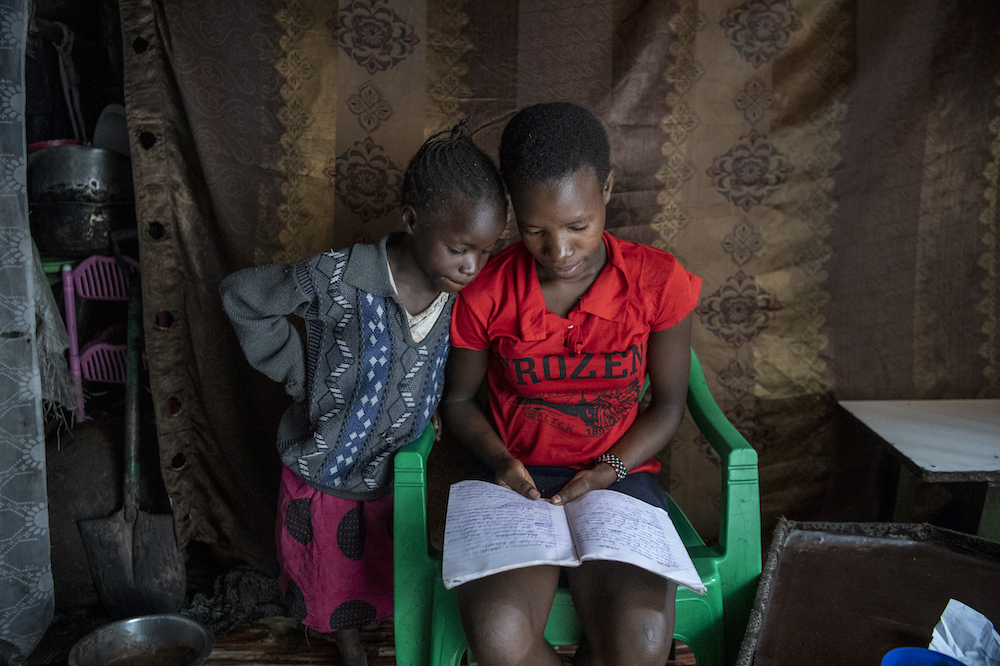

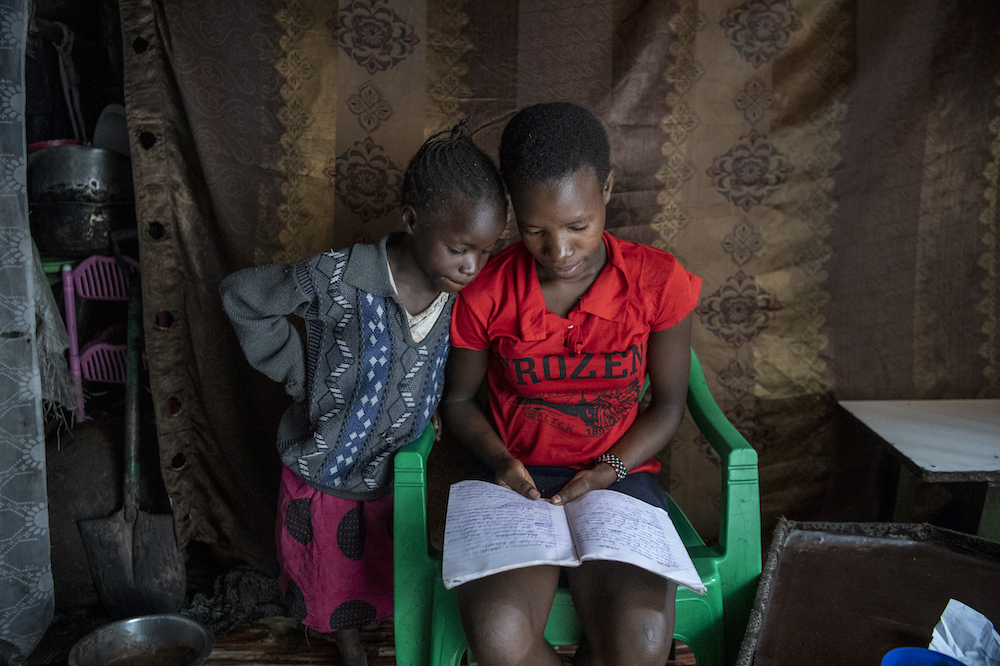

Fifteen-year-old Pilar and her family fled from El Progreso in Honduras to Guatemala after a girl at her school threatened to kill them if Pilar didn’t join her gang as a sex worker.

Gang members followed her home from school to intimidate her. She said: “It was hard to leave my friends, especially because I couldn’t say goodbye. We couldn’t risk the gang finding out.”

In El Salvador, 14-year-old Julieta lives in one of the most violent areas. Her family want to move to a safer country.

Millions of people travel because they can.

Millions of children travel because they must.

#ChildrenUprooted #AChildIsAChild pic.twitter.com/i91IXdlDDT— UNICEF (@UNICEF) August 16, 2018

They are virtually prisoners in their own home and Julieta only leaves to go to a private school. Her brother Rodrigo stays behind because their parents cannot afford to pay for both children to study.

Attending public school is not an option – statistics from 2017 show that 44.61% (2295) of educational centres are located in communities with a gang presence.

According to UNICEF, nearly 24,200 Central American women and children were deported between January and June alone – the majority sent home by Mexico.

Strict immigration controls drive migrants and refugees, including children, to take dangerous routes, said Jose Bergua, UNICEF’s regional advisor on child protection.

To avoid detection by authorities, children move in “the shadows, where nobody knows their whereabouts and where criminal actors take advantage of their invisibility,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

Children account for three in every five victims of human trafficking in Central America and the Caribbean, with organised crime groups behind much of the multi-billion dollar business, according to the UN Office on Drugs and Crime.

“Kids are targeted by traffickers because they are easy to control, they are vulnerable and easy to convince and physically overpower,” said Carol Smolenski, director of the anti-trafficking group ECPAT-USA.

Migrant children are also victims of forced labour – a problem that came to light in 2015 after traffickers lured eight teenagers from Guatemala to the United States.

The teenagers were detained by US authorities who failed to conduct proper background checks before releasing them back into the hands of traffickers, according to a US Senate investigation.

But cases like that won’t stop families and their children trying to leave Central America.

Eric from Honduras said: “My mother decided to leave for the United States with us so we could have a better education, a better life.”

More news