From stone quarry to law school

Child labour

Sumedha Kailash, director of India’s Bal Ashram rehabilitation centre, tells the story of two child labourers whose lives were transformed by education

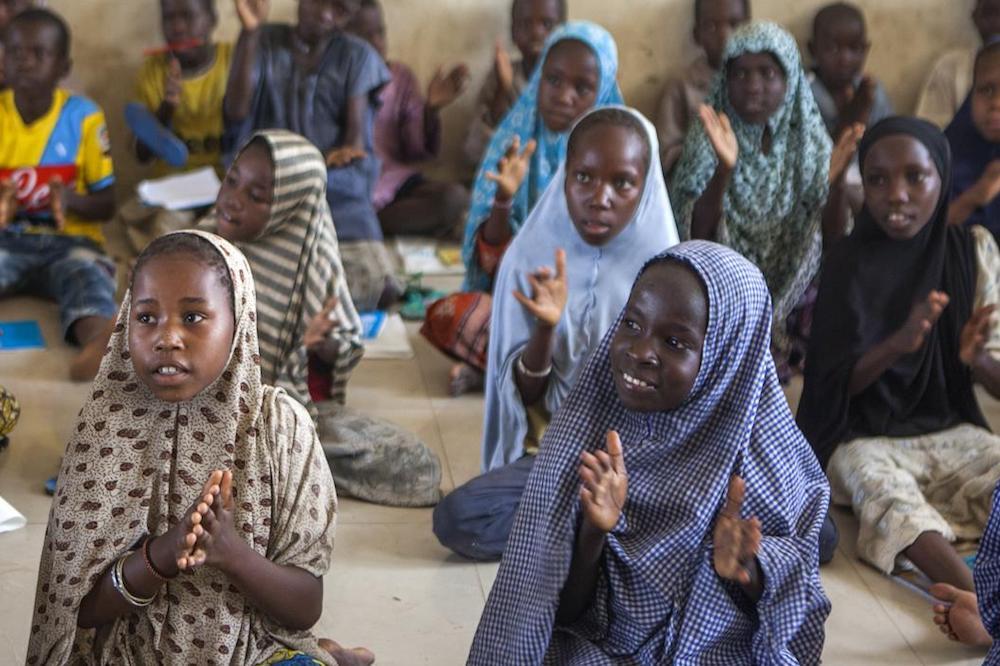

According to a report released last week by the International Labour Organization there are 168 million child labourers around the world. Of these, 85 million are engaged in the worst forms of labour – work detrimental to their physical and mental health, slavery and prostitution. The report, ‘Marking Progress Against Child Labour’, paints a shocking picture.

Many millions of the children whose lives it documents live in India. But India is also home to individual stories that demonstrate the power of education to break the cycle of forced labour, giving children the opportunity to escape poverty and realise their true potential.

In 2007, a group of former child labourers met Gordon Brown, the then UK Chancellor of Exchequer, in New Delhi. Mr Brown has long championed the cause of child education. Among the children were Kinsu Kumar, a former car cleaner, and Amar Lal, born into bonded labour in a stone quarry.

Kinsu was born in 1995 in the Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh in northern India, and started working when he was six years old. Poverty, a lack of information about education or any way to access to it kept him out of school. Amar belongs to the Banjara community, a nomadic Indian tribe that has been socially excluded for centuries. One of six brothers and sisters, he and his family were bonded by debt as labourers to a stone-quarry contractor in Rajasthan.

From a young age Amar would assist his father in breaking stones into smaller pieces. This task had to be done by hand, which meant that Amar had to work with instruments that weighed as much as he did. For this young boy such extreme circumstances made education next to impossible.

At the 2007 meeting, Gordon Brown asked Kinsu what he wanted to be when he grew up. Kinsu told him about his love for mathematics and his ambition to become an engineer. Amar told Mr Brown that he wanted to become a lawyer. Six years on, Kinsu is still working hard, but he isn’t cleaning cars – he is attempting to ace his exams in his mechanical engineering class at a prestigious institute of engineering and technology. For his part Amar has earned himself a place at a prominent Indian law school. Mr Brown’s advice to work hard helped motivate them to achieve their dreams.

The boys’ lives began to change when they were rescued by Bachpan Bachao Andolan, an Indian civil society group founded by the noted activist Kailash Satyarthi in 1980. The organization, of which I am the director, has freed at least 82,000 children like Kinsu and Amar from child labour and slavery. The boys spent more than a decade of their lives in Bal Ashram, a rehabilitation home run by the group where they were fortunate enough to receive an education.

In 2009, Kinsu was invited to speak at a High Level Panel on education at the European Union, convened by the President of the World Bank and Gordon Brown (by this time Prime Minister of Great Britain). He was invited to speak again in 2010, this time at the Global Child Labour Conference at the Hague. At the age of 10, Amar was chosen to be the voice of the world’s out of school children at UNESCO’s High Level Group meeting in December 2007 in Dakar, Senegal.

About a year ago, Amar and Kinsu met Gordon Brown, now the UN Envoy for Global Education, for a third time at their rehabilitation center in New Delhi. Mr Brown recognized Kinsu and remembered his hope to become an engineer.

Kinsu Kumar and Amar Lal were fortunate to be freed from child labour and were able to receive education of good quality. While we at Bachpan Bachao Andolan celebrate their achievements and wait eagerly to see the men they will grow into, we are painfully aware that not every child has the opportunity that these young men did.

Education and child labour are inter-related, and the elimination of child labour is central to the cause of universal education. As well as being the key to the overall development of any individual, education is the key to economic growth and sustainability for any country. On the path to education for all, urgent and coordinated efforts must come from governments to prohibit all forms of child labour.

Amar and Kinsu show vividly the power of education – but they are the exceptions, not the norm. There must be political will in every nation, backed with investment and clear-sighted policies, until one day we can provide education for all the children of the world.

More news