Indian boy’s school project becomes a child labour campaign

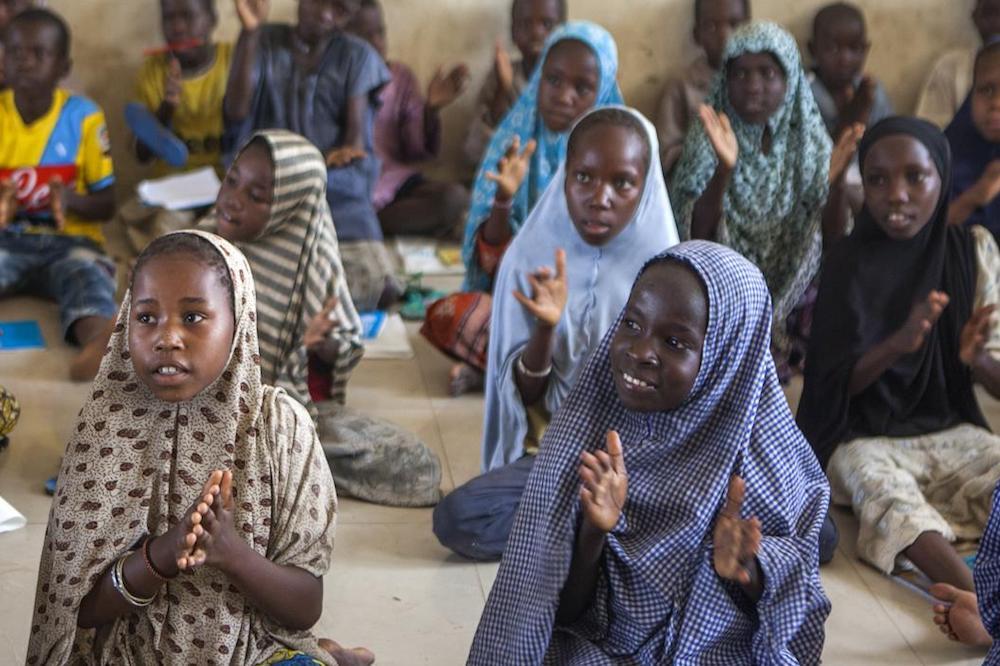

Child labour

It began as a school project, became a citywide campaign and is now a national social media campaign aimed at getting communities to address child labour in India.

Kunaal Bhargava, 17, a student at the American School in Mumbai, picked child labour for a classroom project. He approached Salaam Baalak Trust, a charity that works with street children, for help with material.

The Mumbai police were so impressed with the poster campaign he created that it was adapted for billboards across the city earlier this year.

This week, a citizen engagement platform LocalCircles, which connects its more than one million members in discussions on governance and other matters of public interest, created a discussion group on child labour to seek input on the issue.

“Child labour is an issue I think about a lot, as these are kids as old as me, younger than me, working instead of going to school like me,” said Bhargava.

How child labour affects education hopes of 168 million children

“We encounter it every day, so getting the community involved is an effective way to check child labour,” he told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

There are 5.7 million Indian child workers aged between five and 17, out of 168 million globally, according to the International Labour Organization.

More than half are in agriculture, toiling in cotton, sugarcane and rice paddy fields, and over a quarter work in manufacturing, embroidering clothes, weaving carpets or making match sticks. Kids also work in restaurants and hotels, washing dishes and chopping vegetables, and in middle-class homes.

The Indian government wants to amend a three-decade-old law which bans children under 14 from working in 18 hazardous occupations and 65 processes including mining, gem cutting, cement manufacture and hand looms.

Rescued child labourers protest against the practice in Siliguri

However, children who help their family or family businesses are permitted to work outside school hours, and those in entertainment or sports can also work, provided it does not affect their studies.

Members of the LocalCircles group can, in addition to offering suggestions, post pictures and report instances of child labour that the police and NGOs can act on, said founder Sachin Taparia.

“This platform is more effective than a hotline – how many people will actually remember the number or think to call when they see a child worker in a tea stall or begging on the street?” he said.

“Whereas people are so comfortable taking pictures and posting on social media, and this facilitates that,” he said.

Suggestions from the discussion group so far include stricter punishment for employers of child workers and training programmes for such children, so they can learn skills which could be used to earn an income when they are older.

Poor reintegration of rescued child workers leaves them vulnerable to being trafficked and made to work again, a report by Harvard University’s FXB Center for Health and Human Rights said last month.

The LocalCircles group for child labour is managed by the Indian Police Foundation, a think tank comprising police officials, bureaucrats and civil society leaders.

Community policing has already played a role in fighting child labour and human trafficking, Taparia said, citing police raids on illegal brothels in Delhi and Gurgaon as a result of information given by members of LocalCircles discussion groups.

“The police, the NGOs – we are all doing our bit to check child labour, and having citizens involved will only help create more awareness and rescue more child workers,” said Pravin Patil, a deputy commissioner of police in Mumbai.

The Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, covers humanitarian news, women’s rights, corruption and climate change.

More news