Ivory Coast pushes children into school and out of cocoa labour

Child labour

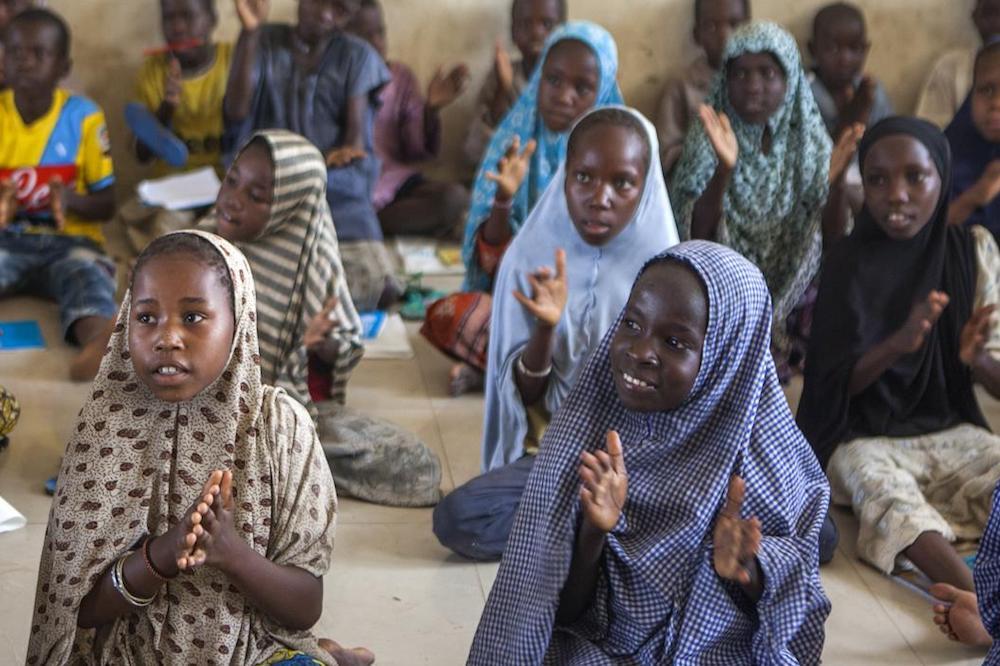

Students in a classroom at the first elementary school built by Nestle in the village of Goboue, in the southwest of Ivory Coast

“At five years old, I went to work in the fields with my dad. Today, my children go to school,” said Peter, a cocoa farmer in Bonikro in the centre of Ivory Coast.

Peter is one of a generation of farmers at the heart of a drive to keep the country’s children in school and away from its vast plantations.

Ivory Coast, the world’s largest cocoa producer, has struggled to prevent children working in the cocoa sector, long an accepted practice in the countryside.

The industry, which accounts for 15% of GDP and more than 50% of export receipts as well as two-thirds of the country’s jobs, is absolutely vital to the country’s economic welfare, according to the World Bank.

But criticism of its record on child labour by consumers and buyers has in the past threatened to tarnish cocoa from the Ivory Coast and undermine its main export, prompting authorities to act.

Out-of-school children carry wood from the cocoa farm

The government’s scheme to get children off the plantations and into school, launched in 2011, is as much about improving the country’s image overseas as it is about protecting its young people.

Sylvie Patricia Yao, the leader of the campaign and chief of staff to the country’s first lady, said that education would help limit child exploitation in the cocoa sector.

“(It) remains for us the alternative and the most effective response in the long-term fight against child labour,” she said.

In 2011, the west African country announced plans to spend almost 20 million euros ($22.4 million) between 2015-2017 to reduce the number of minors working on plantations by 30% by 2017 and 70% by 2020.

Since 2011, 17,829 classrooms have been built or restored, according to the National Monitoring Committee (CNS), which is charged with overseeing the government’s anti-child labour efforts.

It is hoped that the plan will break the cycle of children following their parents into the fields at a young age.

A teacher with a class in the school at Goboue

Djouha Gneprou, a cocoa planter in Goboue in the country’s west, is involved with a school opened by global food giant Nestle in 2013.

“Once the child is in school, they won’t have time to be in the field so they can’t do the heavy work,” he told AFP.

Despite the scheme, recent figures highlight the challenges in the battle.

Between 300,000 and one million children are still estimated to work in the sector, according to a report by the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI), an organisation created by the chocolate industry to fight the exploitation of minors.

Some 4000 child victims of “slavery and exploitation” were removed from cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast between 2012 and 2014, according to authorities.

Whether paid or unpaid, children often come from Ivory Coast’s neighbour Burkina Faso and are used to carry heavy loads, fell trees and spray crops with pesticides.

Girls play in the yard at the elementary school

Nestle, the world’s largest food company and a major consumer of Ivory Coast cocoa, has previously faced criticism from pressure groups for profiting from child labour.

In 2012 Nestle joined the fight against the problem with an information campaign and school construction programme in the areas where it works most.

The company has built 40 schools in four years, according to Nestle-Ivory Coast’s sustainability projects coordinator, Omaro Kane.

In Goboue, the small Nestle-sponsored school has changed the lives of the residents in this town dependent on cocoa production.

“More and more, we send the children to school,” said Gneprou.

Before 2013, the town’s children walked eight kilometres (five miles) every day to reach the school in a neighbouring village.

The village of Goboue, where the school now has 224 students

“It was difficult. The youngest children were unable to go to school because the road is very long,” said Jean Oulai, a cocoa farmer in his 60s and father of six children.

His youngest son, Oulai, 10, is now in his second year of studies at the town’s school.

The modest building with three classrooms, located at the entrance to the village, has become a victim of its own success, struggling to accommodate its 224 students aged between six and 10.

“The first year I effectively had a record with 80 students in the first grade,” said headteacher Denis Kouakou Angoua, who spoke in the school’s courtyard overlooking the very cocoa fields where his pupils would once have been destined to work from a young age.

“Africans believe that a child is someone who will replace them tomorrow,” said one cocoa planter.

“So they want the child to learn the same work that they did. That’s why they take their children with them to the fields.”

Students with their textbooks in French at the school in Goboue

But now the law bans the custom and punishes offenders harshly.

As many as 23 people were convicted, of whom 18 were jailed, for child labour offences between 2012 and 2014, according to Ivorian authorities.

Cocoa farmer Peter takes the threat of imprisonment seriously.

“It’s finished, we don’t send children to the fields anymore. The government said that it’s forbidden and that if we do it then it’s prison,” he said.

© 1994-2016 Agence France-Presse

Learn more about child labour and how it prevents children from going to school

More news