Roma village in Iraq gets its first school in 14 years

Barriers to education, Discrimination of marginalised children, Right to education

Carrying her bag on the way home from class, Malak is glowing – the 10-year-old girl has just finished her first-ever semester of school in her Iraqi Roma village.

In 2004 armed Islamists attacked the village of Al-Zuhour in Iraq’s Diwaniya province, 125 miles south of Baghdad, destroying the only school for the marginalised Roma community.

“On television, I would see other children with school bags and they looked happy,” Malak told AFP. “I was a bit jealous because our school was destroyed years ago,” she said.

The 2003 US-led invasion and the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime had changed things dramatically for the Muslim Roma minority, who had come to Iraq centuries before from India.

During the dictator’s rule, Iraq’s Roma – also called “Kawliya” or gypsies – were primarily known as professional musicians and dancers invited to feasts, weddings and parties.

But since the rise of hardline Islamist groups in Iraq after Saddam’s fall, the Roma have increasingly been persecuted, accused of loose morals and of participating in parties where alcohol was served.

Many of the country’s tens of thousands of Roma have been forced to flee their native villages, often reduced to begging on the streets.

They were insulted and sometimes beaten, so many stopped going to school. Activist Manar al-Zubeidi

The same held true for the people of Al-Zuhour after Islamist fighters attacked the village leaving behind a trail of death and destruction.

For 14 years the village children had no school to go to. But today, thanks to an online campaign, Al-Zuhour’s nearly 100 remaining families have opened a school amid dusty dirt roads often lined with rubbish.

“As soon as we heard about it, I was the happiest person in the world. I begged my father to sign me up,” Malak told AFP, wearing a beige hijab to match her coat.

During her first-ever school semester Malak says she was taught “to read and write, mathematics and sciences”.

Now she “dreams of becoming a school teacher” in her village, home to stone structures with thatched palm roofs.

Before the new school opened, some children from Al-Zuhour tried to continue their studies in nearby villages but they were not welcomed, said activist Manar al-Zubeidi.

“They were insulted and sometimes beaten, so many stopped going to school”, Zubeidi, who helped launch the campaign for the new school, told AFP.

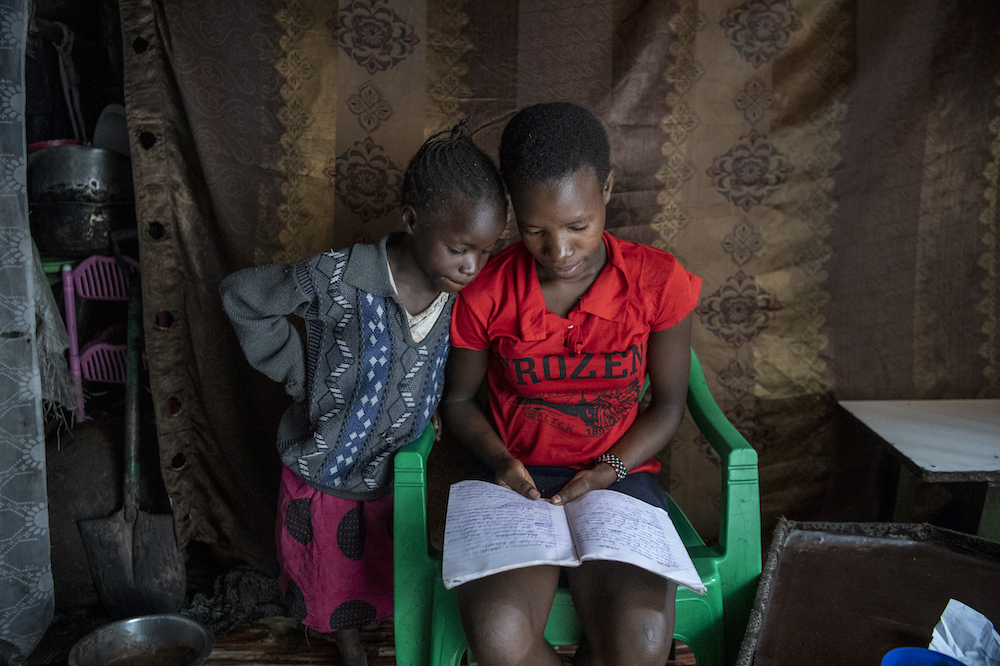

Many children born in the last 14 years have never been able to attend school (UNICEF / Rfaat)

After being turned away by a number of human rights associations, Zubeidi took her campaign to the internet along with several other volunteers using the Arabic-language hashtag “Roma are human”.

The campaign attracted the support of Iraq’s ministry of education, the government body for human rights and the United Nations children’s fund UNICEF.

Once the material for the school was obtained, it became necessary to recruit teachers. But “social barriers” still exist, said Zubeidi.

Many candidates declined the job for fear of being associated with the Roma of Diwaniya, the second poorest province in Iraq.

Qassem Abbas, who was tipped to become the principal of the newly-named Al-Nakhil (Palm Trees) school, said he was initially hesitant and concerned about his reputation in the tribal province.

“But when I knew that these children had no school for 14 years, I reminded myself that I worked in education to teach everyone, regardless of their gender or origin, so I accepted,” he told AFP.

Abbas stuck with the job despite being the target of criticism on social media, he said. He teaches a group of 27 primary schoolchildren with the help of two other teachers. Their efforts were clear at the end of the first semester.

“90% of the students passed the final exams – and many with high marks,” he said.

When Al-Nakhil school first opened it was set up in a tent but it now comprises nine prefabricated rooms – six for the school proper and three that serve as an infirmary.

Haydar Sattar, the UNICEF representative in Diwaniya, said the infirmary provides health services to the students and the rest of the village.

“The people of Al-Zuhour face forms of sectarian discrimination, marginalisation and racism,” he said. “But the most important issue (until now) was the lack of education services.”

Al-Nakhil soon hopes to expand educational opportunities to adults in the village, and is planning “literacy classes” specifically aimed at women, he added.

More news

We need collective action to improve girls’ education: Theirworld Chair Sarah Brown