Solar panels are helping to keep Kenyan kids in school

Right to education, Technology and education

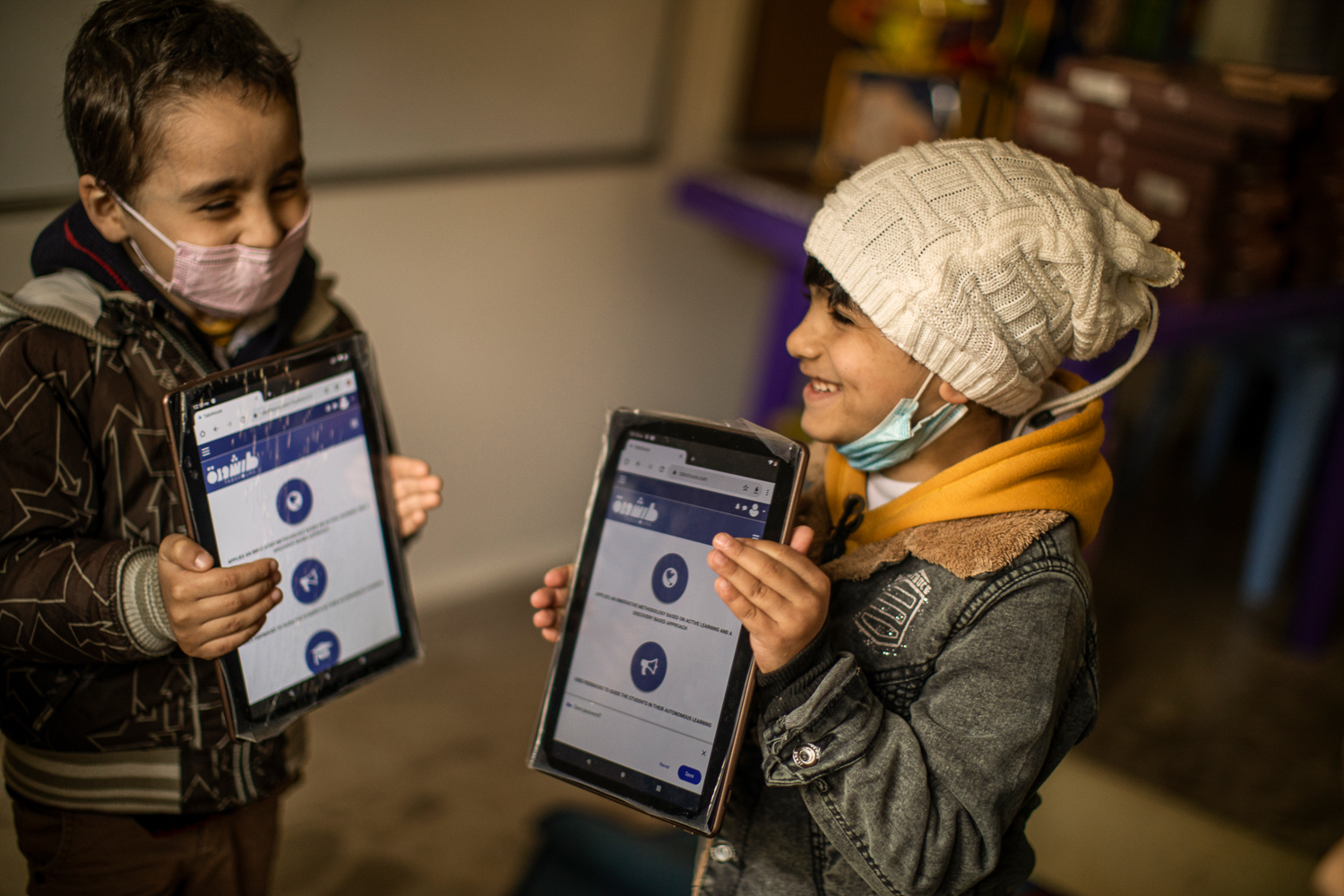

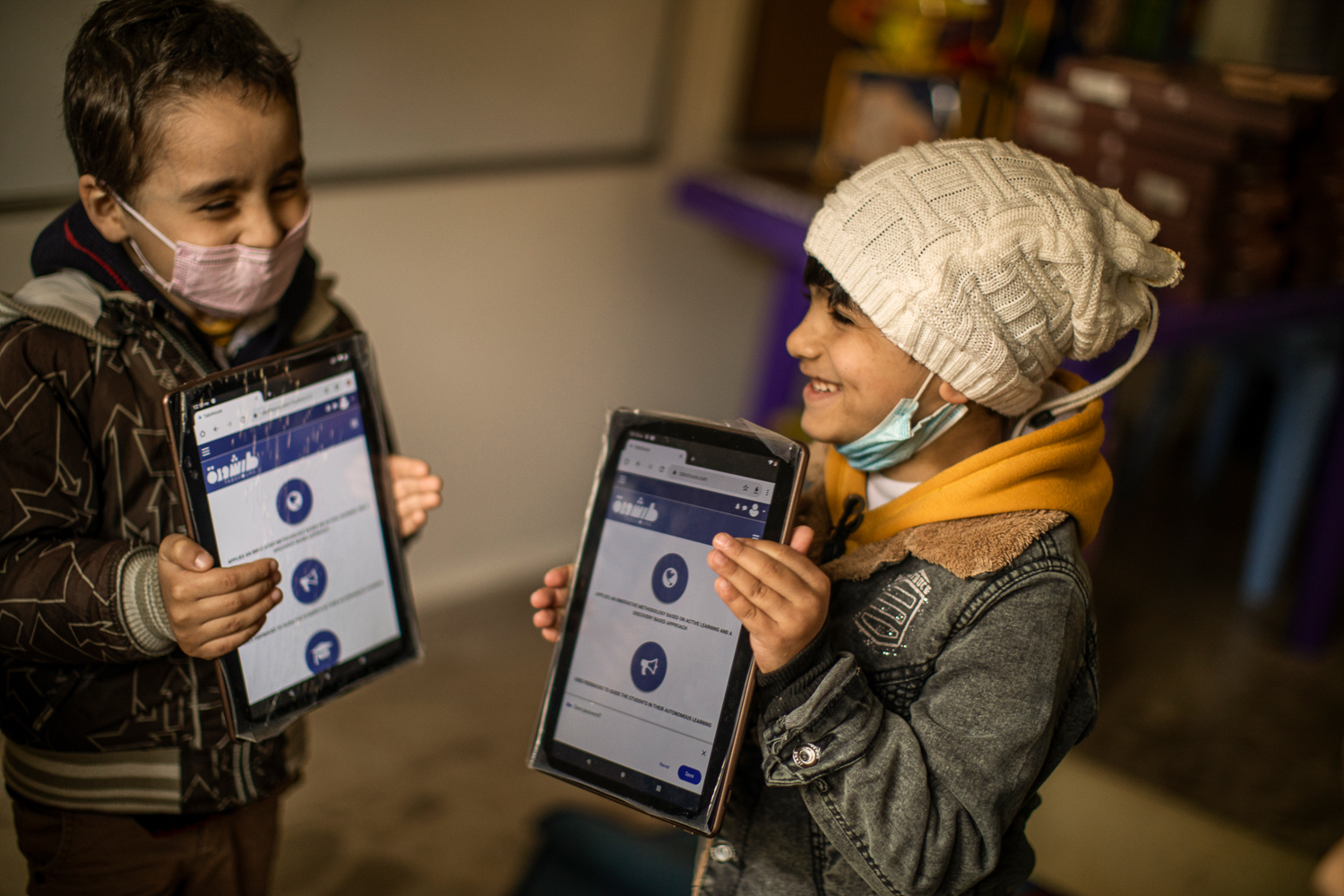

With thousands of schools not on the electricity grid, sunshine is used to power many of the one million tablets that were given to primary students.

From a mile away, the roof of Mihingoni Primary School glitters in Kenya’s midday sun. The effect, though, comes not from the roof but from what is on it – a sparkling array of solar panels.

Mihingoni is one of eight mostly off-grid primary schools in the southeastern coastal county of Kilifi that have been fitted with a solar array.

The key task of the 800-watt panels is to power tablet computers that pupils use under the government’s strategy to integrate e-learning into primary education.

Last year more than one million of the devices were distributed to primary school students across the country – among them Mihingoni’s pupils. But tablets require electricity, which many rural schools lack.

Mihingoni primary is connected to the national grid. But power is expensive and only its computer room has electricity, limiting charging of the devices.

But “since the solar panels were fitted (in January), pupils can have access to their tablets any time and the cost of power has considerably gone down,” said Kuchanja Karisa, headmaster of the school, about 22 miles north of the coastal city of Mombasa.

In his impoverished area, he said, access to electricity boosts access to education, not least because the cost of power is factored into school fees.

“Poverty levels in this area are high and any slight increase or decrease in school fees affects school attendance,” he said.

The panels are part of a project run by two British-based organisations to provide solar power to primary schools and clinics in remote, off-grid communities.

The OVO Foundation – the charitable arm of a green-leaning energy firm – provides funding, while Energy 4 Impact, a charity that works on accelerating access to energy, does the installation.

The need is great. Thousands of Kenyan schools lack access to the national power grid.

Figures from the education ministry show the country had 29,460 primary schools as of 2014, of which nearly 22,000 were state schools. As of last December, about 24,000 primary schools were connected to the grid, according to Simon Gicharu who chairs the government’s rural electrification programme.

A lack of power at unconnected schools, however, makes it difficult for students to take full advantage of tablets provided under the e-learning programme, Karisa said.

At Mihingoni, for example, pupils unable to access the computer lab to charge their tablets – which have an eight-hour battery life – ended up using them less, the headmaster said.

At the school, students previously paid 1500 Kenyan shillings ($15) a year for electricity. But today, with the solar panels, there is a much lower fee – 500 shillings ($5), which goes to pay for more grid power in the rainy season when the solar panels work less effectively.

Cutting costs “has seen a sharp increase in the number of students who have since joined the school”, Karisa said.

In 2017, the school had about 50 pupils in each class, he said. Now it has 140, with the lower cost encouraging more parents to send their children to school.

Annual fees at the school are about 700 shillings ($7) per primary school student, apart from the energy supplement.

“Every coin counts for area locals,” Karisa said.

Fifty kilometres north is Migodomani Primary School, which also had solar panels installed in January.

Headmaster Ngala Kahindi Luwali told the Thomson Reuters Foundation that until the panels were available, his pupils had been unable to use tablets at all.

“With the solar panels we have been able to catch up with other schools in urban areas that have already incorporated e-learning,” he said. “Pupils are enthusiastic with e-learning since it’s a new method of teaching.”

Gaby Sethi, who heads the OVO Foundation, said she believes providing access to clean electricity in parts of the world without power can help people get ahead.

“We think we can have a significant impact on people and children’s lives if we’re electrifying schools and health clinics,” she said.

More news

Girls in ICT Day 2022: Nurturing Tanzanian girls’ future career paths in STEM