Leaving the Youngest Behind: Declining aid to early childhood education (April 2019)

Declining aid to early childhood education.

Theirworld Leaving The Youngest Behind 2Nd Edition April 2019

Introduction

Around the world rich and poor countries are failing to deliver on the promises made to the world’s youngest children, risking their development and future life chances.

The stage from birth to five years is the most important in a child’s development, when over 90 per cent of brain development takes place. Along with adequate nutrition, good health care, protection and play, early learning is fundamental for a child’s full development. Learning begins at birth and occurs in many ways, including interaction with parents, family and community and play; but pre-primary education – also known as early childhood education, pre-school, kindergarten, and nursery – is now widely recognised as critical for children to reach their full potential. Not only does it stimulate cognitive and emotional development, but there is robust evidence of pre-primary education’s impact on school completion and learning outcomes in later childhood, as well as lifelong benefits in terms of health and earnings. Nor does it just impact on school attendance or completion: children who receive pre-primary education do consistently better in mathematics, science and reading, even after accounting for socio-economic factors.

Without access to good-quality, equitable and inclusive early childhood education, children risk being left behind, limiting their ability to learn and thrive in school and later life.

Pre-primary education is the most effective way of promoting equity in education and beyond. It has particular benefits for children from the most disadvantaged backgrounds, including children growing up in vulnerable situations and children with disabilities.

And the returns on the investment pay off.

It has been estimated that returns on investing just $1 in early childhood care and education can be as high as $17 for the most disadvantaged children. In Sub-Saharan Africa it has been estimated that every dollar spent towards tripling pre-primary education enrolment would yield a $33 return on investment.

Given the well-known benefits, world leaders made a commitment that by 2030 all children would have access to at least one year of quality pre-primary education.

Yet globally 175 million children are still out of pre-primary education, denied this fundamental stage in their learning and development. There is a stark divide between children in the richest nations and those in low-income countries, with more than 80 per cent of children in high-income countries attending pre-primary education, and more than 80 per cent of those in low-income countries denied access.

For the most marginalised children, especially the poorest children, disadvantaged girls, children with disabilities, and those living in low-income and vulnerable situations – including conflict-affected countries and countries with a high prevalence of HIV – access to quality early childhood education remains elusive. To address this imbalance and give all children a fair start in life, governments need to ensure pre-primary education is prioritised and funded in their national education plan, and international donors must ensure no child is left behind by supporting these efforts.

Rhetoric and Inaction

While many donors increasingly voice their recognition of the importance of early childhood education, few are matching their public statements of support with tangible investment in pre-primary.

This report provides analysis of donor spending on pre-primary education based on the most recent data reported to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, Development Co-operation Directorate (OECD-DAC), highlighting the gap between rhetoric and reality. It tracks progress in aid spending over the past two years to identify changes since Theirworld’s 2017 ‘Bright and Early’ report, demonstrating which actors in the international community are stepping up to support the internationally agreed Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) targets, particularly target 4.2 which calls for all girls and boys to have access to quality pre-primary education by 2030.

The news is not good.

The analysis reveals that 16 of the top 25 donors to the education sector have either given nothing or reduced their previous spending on pre-primary education since the introduction of the SDG targets. And since the promise to give all children access to quality pre-primary education was made in 2015, aid spending on pre-primary education has declined by more than a quarter. As a result, aid spending on pre-primary education is even smaller than when the SDGs were adopted in 2015.

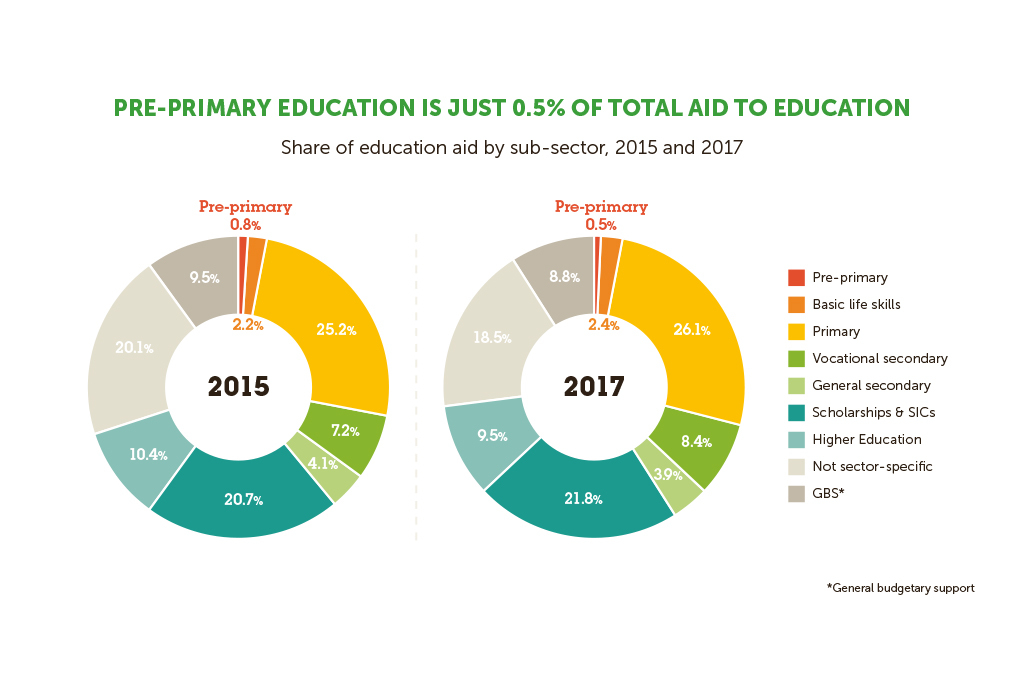

While there has been an increase in overall aid to education, aid to pre-primary education is a small, and declining, priority of overall aid spending, accounting for just 0.5 per cent in total in 2017 – down from 0.8 per cent in 2015. The allocation of overall education aid to pre-primary schooling is similar for conflict-affected countries, also amounting to only around 0.5 per cent. While higher than the average, funding for early childhood education in countries with high prevalence rates of HIV stands at 0.9 per cent, still woefully below the recommended 10 per cent target. Despite their promises, donors are failing the youngest and most vulnerable children.

Adding to the shocking lack of financial support for pre-primary education is the fact that donor spending is reinforcing inequity.

In the same period that donor spending has declined overall for pre-primary education, aid funding scholarships for higher education among young people who have completed secondary school has increased. Donor spending on scholarships is now 42 times higher than donor spending on pre-primary education.

This reality in pre-primary education aid spending is contrary to the SDG 4 priority of leaving no one behind, and the principle articulated by the International Commission, which identified the need for an approach to public spending based on ‘progressive universalism’. This approach recognises the importance of investment in all levels of education, but highlights the need to prioritise public spending to address inequity at its very beginning, at the first stage of education, by prioritising the youngest and most marginalised. By contrast, the current pattern of aid spending is primarily benefiting children from wealthier families who have already reached advanced levels of education.

Unfortunately, it does not seem that this pattern is expected to change any time soon. Financing commitments for the coming year (as represented in the aid budget) similarly show a declining trend.

A lack of donor support to pre-primary education means millions of the world’s youngest children, in particular girls, children with disabilities and children living in vulnerable situations, are being left behind. An urgent prioritisation of aid spending on pre-primary education is needed to incentivise governments to make serious investments in early learning and deliver the promise of SDG 4 and the sustainable development agenda, where no one is left behind.

Key messages

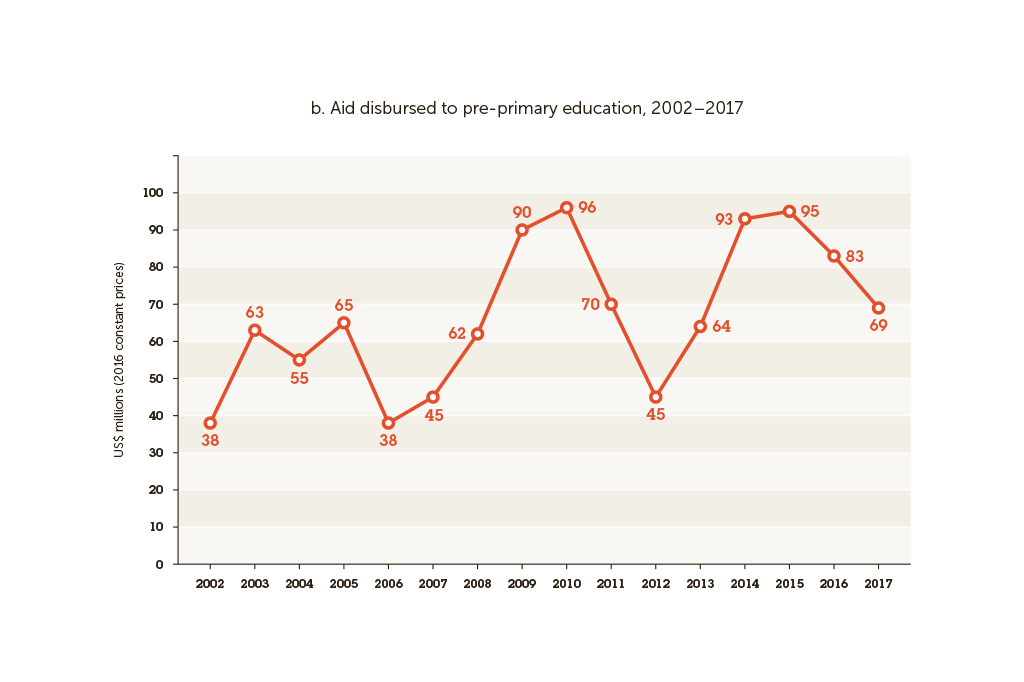

- Between 2015 and 2017, aid spent on pre-primary education declined by 27%, from US$94.8 million to US$68.8 million. This occurred against a backdrop of a more general increase in aid to education: over this period, total aid to education rose 11%.

- 16 of the top 25 donors to the education sector in 2017 either gave nothing or reduced their previous spending on pre-primary education.

- In 2015, pre-primary education’s share of total education aid was 0.8%. In 2016, this fell to 0.6%. In 2017 it declined further to 0.5%.

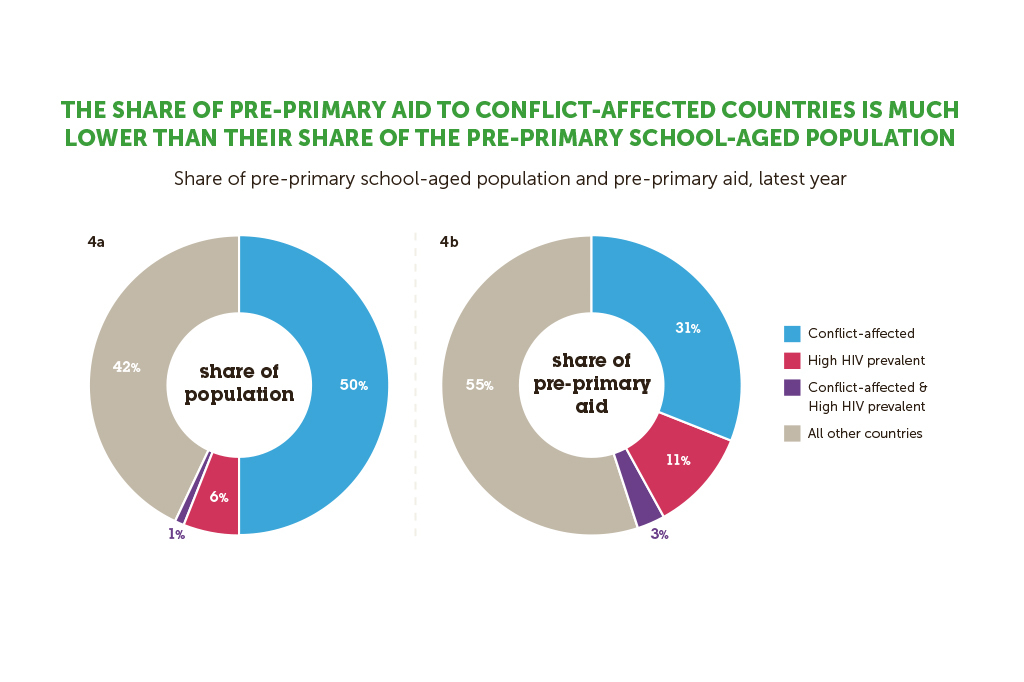

- The youngest children in the most vulnerable situations are even more neglected. While one-half of the pre-primary school-aged population live in conflict-affected states, they receive less than one-third of pre-primary education spending.

- In countries with high HIV prevalence rates where 7% of the pre-primary school-aged population live, children receive 11% of pre-primary education spending. While they fare better, given their needs, they require a larger share of the scarce resources.

- While donors’ spending on pre-primary education has been declining, aid to fund higher education scholarships has increased during the same period. In 2017, aid spending on scholarships was 42 times more than for pre-primary education.

- Aid to pre-primary education is precarious. Taking into account the small number of donors to education, together with the even smaller number who disburse significant funds to the pre-primary sub-sector, and without greater political commitment, investment in pre-primary education is at high risk of volatility year-on-year.

- Of the 25 top donors to education, only 15 reported any financing commitments at all to pre-primary education in both 2015 and 2017. Of these, nine donors have decreased their commitment, signifying a worrying trend at odds with donors’ own policy statements.

Trends in pre-primary education aid: 2015–2017

Aid spending on pre-primary education is on the decline

Not only is aid spending to pre-primary education already low, but, even more worryingly, it is on the decline.

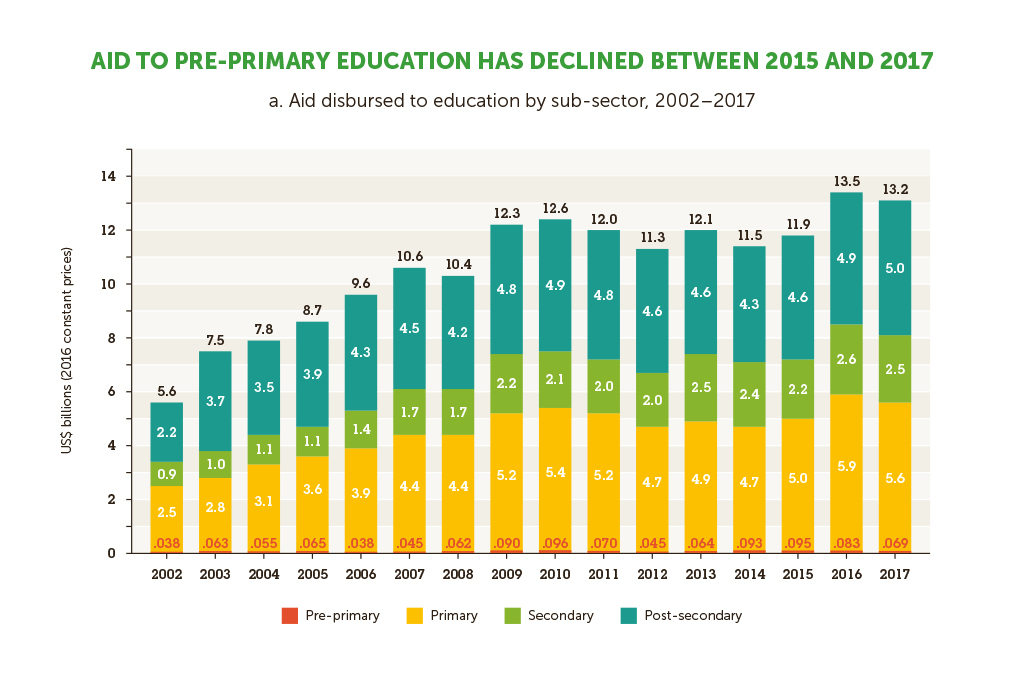

Between 2015 and 2017, aid spent on pre-primary education fell by 27 per cent, from US$94.8 million to US$68.8 million. This downward trend comes against a backdrop of a more general increase in aid to education: over this period, total aid to education rose by 11 per cent. Primary education and post-secondary education witnessed an increase of 10 per cent in aid levels disbursed between 2015 and 2017, while levels disbursed to secondary education increased by 14% (from a lower base) over the same period (Figure 1).

The large fall in aid spending to pre-primary education – compared to increases in education aid overall – means that pre-primary education’s share of total education aid has decreased over time. In 2015, pre-primary education’s share was 0.8 per cent. In 2016, this fell to 0.6 per cent. In 2017 it declined further to 0.5 per cent (Figure 2). By comparison, the share of total education aid spent on scholarships for higher education students to study in donor countries was 22 per cent in 2017, up slightly from the 2015 level of 21 per cent. In volume terms, aid spending on scholarships was 26 times more than the amount spent on pre-primary education in 2015. By 2017 the equivalent was 42 times more.

Pre-primary education is becoming a lower priority in education spending for many donors

Of the top 25 donors to the education sector in 2017, seven reported that they did not spend any of their aid on pre-primary education (Table 1). These include the United States, the second largest donor to education overall, together with UNRWA, the Asian Development Bank, Austria, the African Development Fund, Sweden and the Netherlands. Out of these seven donors, only Austria had disbursed aid to the pre-primary sector in 2015.

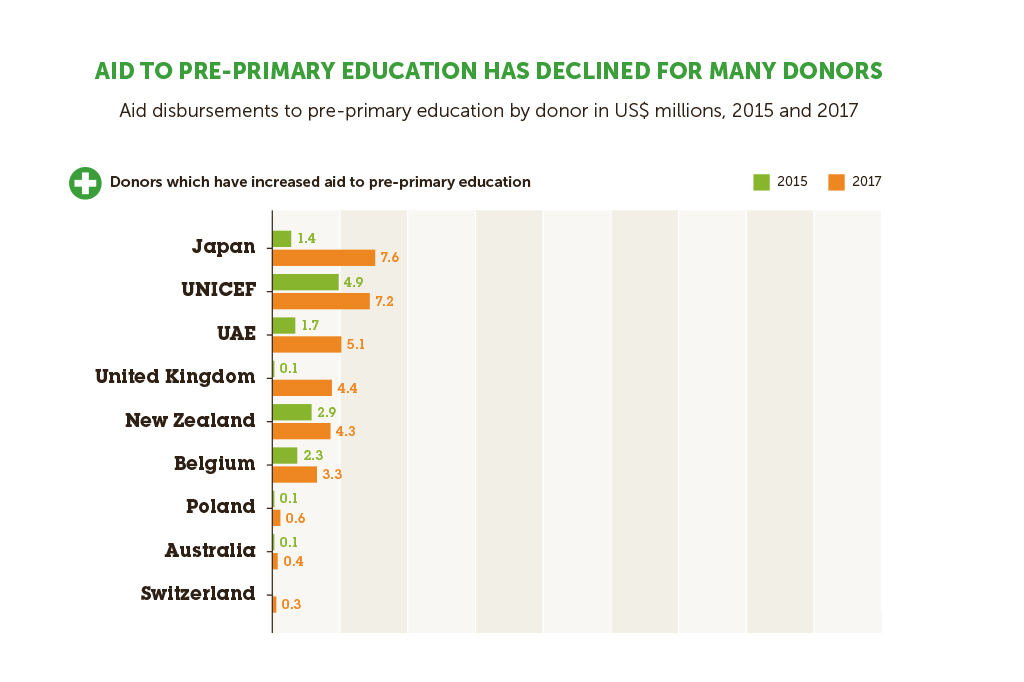

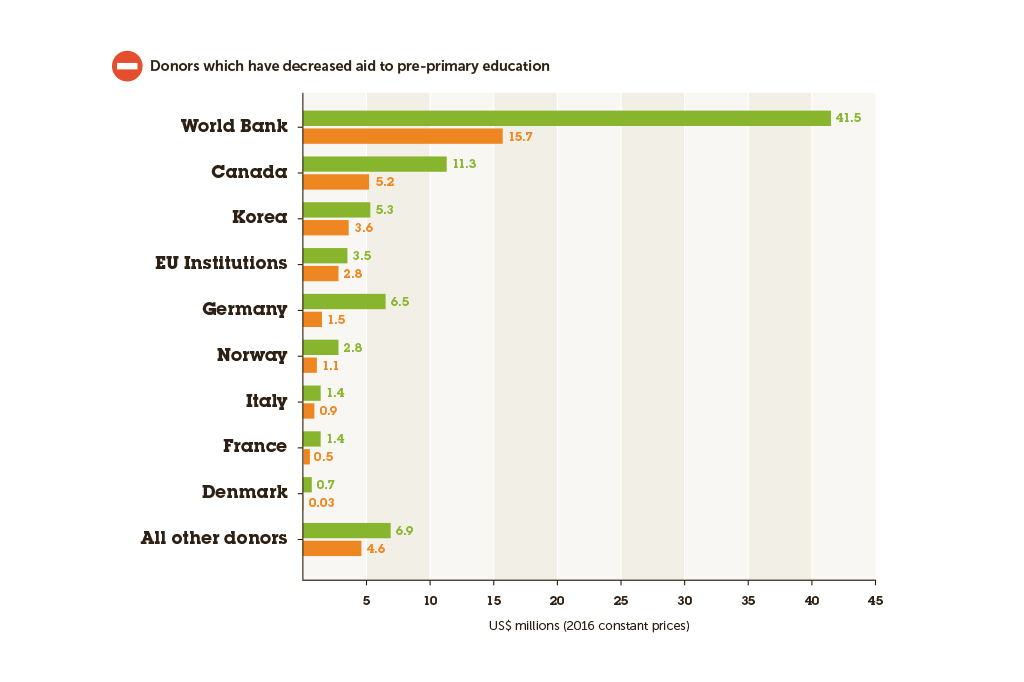

Of the other 18 donors amongst the top 25, who did spend on pre-primary education, nine decreased their aid spending on pre-primary education between 2015 and 2017. These included Canada, EU Institutions, Korea and the World Bank, who were among the largest pre-primary education donors in 2017. The remaining nine donors – including Japan, UNICEF and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) – increased the amount spent (Figure 3).

As a result of these changes, UNICEF now is ranked number one in terms of prioritisation of aid spending to pre-primary education as a share of its overall aid to education. It should be noted that this is in the context of a small decline in their overall education spending. While the World Bank remains the largest donor in volume terms, its ranking has fallen from number four to number six in terms of its prioritisation of the sub-sector (Table 2).

NB. The data included in this report is taken from the OECD DAC-CRS database, according to reporting by donors using agreed classifications for the database. The data in this report shows actual disbursements made to countries based on each donor’s reporting. Independent of this, the World Bank has prepared a publication: “World Bank Investments in Early Childhood Education.” This provides a recent portfolio review of all the World Bank Group investments in early childhood education using a methodology which allows for these activities within basic education projects to be counted separately. This analysis suggests new project approvals of $140 million in the financial year 2017 allocated to ECE, based on country demand. However, approval does not mean the funding was necessarily disbursed in 2017.

Aid spending to pre-primary education continues to remain extremely concentrated among a small number of donors. The top five donors were responsible for 59% of pre-primary spending overall in 2017: the World Bank, Japan, UNICEF, Canada and the UAE. Of these top five donors, the World Bank and Canada decreased the amount that they disbursed to pre-primary education between 2015 and 2017.

In 2017, these five were the only donors to disburse more than US$5 million. The small number of donors, together with an even smaller number who disburse significant funds to the sub-sector, continues to leave pre-primary education at risk of great unpredictability in investment year-on-year. For instance, the largest donor in volume terms – the World Bank – was responsible for 44 per cent of total pre-primary aid in 2015. Despite remaining the largest donor in volume terms in 2017, the fall in the World Bank’s aid to pre-primary education between 2015 and 2017 saw this share of pre-primary education spending plummet to 23 per cent in 2017.

The Global Partnership for Education (GPE), which does not report its aid directly to OECD-DAC, identifies early childhood care and education as one of its priority focus areas. In 2017, of the US$482 million that was disbursed by the GPE, US$25 million – or 5 per cent of the total – was for early childhood care and education. Unfortunately, GPE does not provide sufficient breakdown of its financing to be able to provide comparable analysis to other donors.

Conflict-affected countries receive an even smaller share of pre-primary aid spending

One in every two children of pre-primary-school age in aid-recipient countries lives in a country affected by conflict. However, these countries received less than one-third (just 31 per cent) of aid spent on pre-primary education in 2017.

Countries with high HIV prevalence fare better: 7 per cent of the total pre-primary school-aged population in aid-recipient countries live in these countries, and they received 11 per cent of pre-primary education aid in 2017 (Figure 4). Arguably, given that these countries face greater obstacles in reaching some of the world’s most vulnerable young children, they should require a greater share still of the very scarce resources.

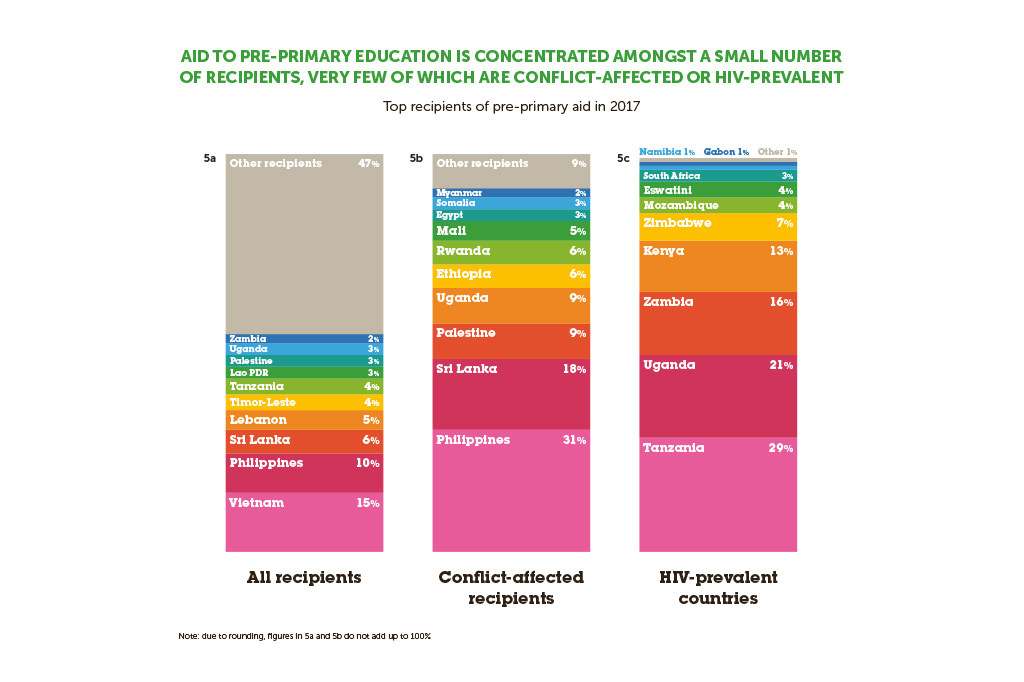

Just as donors remain quite concentrated, so do the recipients of pre-primary education aid. In total, 41 aid-recipient countries received no aid to pre-primary education in 2017. Of these 41 countries, five are conflict-affected and three are HIV-prevalent.

The top ten recipients overall received over half of the total pre-primary spending in 2017. Within this group of 10, four are conflict-affected countries: Philippines, Sri Lanka, Palestine and Uganda, and three are countries with high rates of HIV prevalence: Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia (Figure 5A).In addition, Lebanon, which currently hosts a significant proportion of refugees supported through its public education system, is in the top 10 of overall aid recipients.

Within the list of 30 conflict-affected countries, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Palestine, Uganda and Ethiopia were the top five recipients of pre-primary aid, representing almost three-quarters of spending within this group of countries (Figure 5B); meanwhile five (Libya, South Sudan, Sudan, Turkey and Yemen) received no aid at all for pre-primary education in 2017.

Of 15 countries identified as having high rates of HIV prevalence, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Kenya and Zimbabwe were the top five country recipients, representing 86 per cent of spending within this group of countries (Figure 5C); while three (Botswana, Central African Republic and Eritrea) received no disbursements for pre-primary education in 2017.

The majority of pre-primary education aid is disbursed to lower middle-income countries, which received 64 per cent of global disbursements in 2017. This is slightly higher than their share of the 3–4-year-old global population, which is around 52 per cent.

23 per cent went to low-income countries, which represent 18 per cent of the pre-primary school-aged population. But around 13 per cent went to upper middle-income countries, which comprise around 29 per cent of this population group.

It seems, therefore, that low- and lower middle-income countries receive a relatively equal share of the minimal pre-primary education aid spending. However, this raises questions of whether principles of fairness associated with progressive universalism are being adopted by donors, which would imply that the poorest countries that are most in need should receive a larger share.

The low levels of aid disbursed to pre-primary education means aid spending per pre-primary aid child is low.

On average, each pre-primary school-aged child in aid recipient countries only received US$0.27 in aid to support early learning in 2017.

The situation is even more stark for a pre-primary school-aged child residing in a conflict-affected country, who will have received on average just US$0.17 in aid (Table 3). A pre-primary school-aged child residing in an HIV-prevalent country fared slightly better, receiving US$0.50 on average. But even this is woefully low.

There are of course wide variations amongst those countries receiving at least some aid for pre-primary education. In total, there are just 28 countries where a pre-primary school-aged child received on average more than US$1 in aid. In the case of conflict-affected countries, a pre-primary school-aged child in Palestine, Philippines, Rwanda and Sri Lanka received an average aid investment of more than US$1. Chad and Cameroon, on the other hand, received less than US$0.10 per pre-primary school-aged child. Similarly, in HIV-prevalent countries, a pre-primary school-aged child in Eswatini and Zambia received aid investments of more than US$1 on average. Zambia receives almost 21 times more in aid for pre-primary education (US$1.30 per child) compared to neighbouring Malawi (US$0.06).

Donor spending commitments to pre-primary education

While donor spending patterns give a window onto how donors have been changing their priorities towards pre-primary education, they do not necessarily help predict changing financial commitments for the future. This is important to assess given that some donors are increasingly highlighting the importance of pre-primary education in their policies.

Overall donor financial commitments to pre-primary education have followed the same trend as their spending, falling by 31 per cent between 2015 and 2017. Of the top 25 donors to education in volume terms, only 15 donors reported that they were committing resources to pre-primary education in both 2015 and 2017. Of these, six have increased their commitment to pre-primary education over this period (UNICEF, Belgium, Japan, Poland, Norway and Australia). The remaining nine have decreased their commitment (New Zealand, Canada, Korea, World Bank, Italy, United Kingdom, Germany, France and Denmark). This is a worrying trend that implies that spending might not improve in the near future and does not seem to reflect recent policy statements by some of these donors (see below).

Donors urgently need to reverse their spending on pre-primary education for 2030 targets to be met

In our 2018 donor score-card, we calculated the aid targets to reach the 2030 SDG on pre-primary education. The 2030 target assumed all donors would disburse 0.7 per cent of their national wealth towards aid of which 15 per cent would be spent on education; and within the education spend, 10 per cent would be specifically for pre-primary education. This target would mean that by 2030 US$5.8 billion would be disbursed to pre-primary education annually (Table 4).

Given the relative size of its economy, the United States would be responsible for a large proportion of this amount (26.6%), followed by EU Institutions (10.2%), World Bank (7.4%), Japan (7.0%) and Germany (6.2%).

On average, if donors were to meet these targets by 2030, aid disbursed to pre-primary education would need to increase by 41 per cent every year between now and 2030. This means there is an urgent need to reverse the downward trend in pre-primary aid spending, with spending in fact needing to increase at an unprecedented pace.

Donor promises, policy and practice

Not only is donor financing at odds with the SDG 4 commitment, donors are often falling short of their own policy priorities.

Of the 34 donor policy statements and official strategies reviewed, only 17 have a defined policy of supporting pre-primary education within their overall education programs. An additional two donors informed us that although it is not part of their formal policy framework, support for pre-primary education does form part of their internal guidelines. At least one other donor reported that they do support pre-primary education; however, they have no policy or guidelines in place to direct the investments.

Of the 17 donors with an explicit policy focus on pre-primary education, 11 have a focus on inclusion at pre-primary education, including children with disabilities. Of these same 17 donors, 11 also include a specific focus on pre-primary education in conflict-affected countries. Only two donors, the United States and Ireland, made support to children affected by HIV at pre-primary level explicit in their development policies, and a few other donors had a clear focus on education for children affected by HIV with implied support for early childhood education.

While making provision for marginalised populations in donor policies is an important step, we find that regardless of whether support for pre-primary education for children in conflict-affected countries or impacted by HIV/AIDs was an explicit or implicit policy priority, not all donors provided sufficient funding for pre-primary education for these marginalised groups.

Donor support and domestic prioritisation of pre-primary education are both important

Along with donor support, governments’ domestic policy and spending must also prioritise pre-primary education to meet the 2030 targets.

Recent analysis shows that only 45 per cent of countries globally provide tuition-free pre-primary education, a figure which falls to 15 per cent for low-income countries. Governments around the world need to review their policies and their spending on pre-primary education to ensure that all children have the best start in life.

When governments prioritise pre-primary education and work together with the international community to finance and deliver on this policy priority, the impact can be significant.

Vietnam is one such success story and now boasts a pre-primary net enrolment rate of 99 per cent, an increase of 35 per cent in less than a decade. This success has been achieved through a combination of domestic prioritisation and international support. In 2015 Vietnam allocated 16 per cent of its education budget to pre-primary education. Vietnam has also benefited from a high level of donor support. In 2015, when the World Bank was the largest donor to pre-primary education in terms of both percentage and volume, 73 per cent of its total aid disbursements to pre-primary education went to Vietnam. In 2017, Vietnam was one of the top ten recipients of all donor ODA for pre-primary education – accounting for 15 per cent of the total ODA to pre-primary education.

Palestine, despite the challenges it faces, has also made significant progress in pre-primary education. Net enrolment now stands at 62 per cent, representing growth of more than 20 per cent in net enrolment rates in the last decade. In May 2016, the Palestinian Authority launched the first Palestinian national curriculum framework for kindergarten education and the Minister of Education and Higher Education said ‘early childhood education is the mechanism to attain our future as a nation.’ In addition to increasing the recognition and prioritisation of pre-primary education in the country, Palestine has also benefited from international financial support, accounting for 3 per cent of all donor aid to pre-primary education in 2017. Nevertheless, more donor support is needed for Palestine – and for all conflict-affected countries, which as a group receive less than one-third of all donor aid to pre-primary education.

Tanzania, a country with a high prevalence of HIV, is another example of progress, albeit expenditure is still far from the SDG 4.2 target. Net enrolment for pre-primary education has increased by more than 20 per cent in less than a decade and in 2017 had reached 51 per cent. The growth in pre-primary education was given a boost in 2015, when the Government of Tanzania introduced the ‘Fee Free Basic Education Policy’, which commits to the provision of free education, including for pre-primary, of which one year is compulsory. In 2014, government expenditure on pre-primary education accounted for 6.03 per cent of total government expenditure on education. Progress in pre-primary participation in Tanzania has also benefited from ongoing donor support; in 2017 Tanzania was in the top ten of all recipients and received 4 per cent of all ODA to pre-primary education.

Pre-primary education is important for all children and its benefits are particularly important for children from disadvantaged backgrounds, the poorest children, children with disabilities, girls and children affected by HIV and AIDS.

With the support of the international community to make pre-primary education a policy and funding priority, substantial progress can result. While donor aid is only one aspect of financing early childhood education, it often influences priorities in the global community and in domestic policy.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Too few donors are prioritising pre-primary education despite the robust evidence of the short-, medium- and long-term benefits for children, their education, skills and lifetime earnings. Urgent action is needed to address the shortfall in international financing available to pre-primary education.

Without attention to pre-primary education, countries will fail to achieve the goal of inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong learning promised by SDG 4.

Millions of children risk being denied the benefits that pre-primary education brings in terms of school completion, increased learning and better lifelong outcomes in terms of health and earnings. In particular the most marginalised and vulnerable children – those from low-income households, girls, children with disabilities, and children living in conflict-affected countries, and in countries with high HIV prevalence rates – run the greatest risk of being left behind.

To support the realisation of SDG 4.2, Theirworld recommends that the international community takes the following action to prioritise pre-primary education and change course for the next generation:

-

Strengthen – and implement – policy commitments to pre-primary education, making pre-primary education a clear part of every international donor country and agency’s education strategy.

-

Increase spending on pre-primary education to reach 10% of the total education ODA, setting targets for 2020, 2025 and 2030 and for achieving fair share levels of support for pre-primary education.

-

Channel priority grant funding to countries most in need, including low-income countries, conflict-affected countries, and to countries and communities with special circumstances and obstacles, including communities with high levels of HIV/AIDS.

-

Target ODA to pre-primary education for the most marginalised groups of children, including the poorest, children with disabilities, girls and minority groups.

-

UNICEF, as the donor giving highest priority to pre-primary education in 2017, and a strong advocate for early childhood development, should lead by example and reach the pre-primary education target of 10%.

-

The World Bank, the largest donor in volume terms, should reverse the recent decline in aid to pre-primary education and make a public commitment to increase the total share of education ODA to pre-primary education to at least 10%.

-

Given the low investment in early childhood education in countries affected by conflict, Education Cannot Wait should increase its spending on pre-primary education to at least 10% of its total budget and incentivise its partners to prioritise early learning in its first-response and multi-year response plans.

-

The Global Partnership for Education should increase allocations to pre-primary education from an average of 5% to at least 10% of its budget, setting an example for the broader international community. It should also improve its reporting on annual financing of the sub-sector, to allow accurate tracking of this spending.

-

The International Finance Facility for Education should promote early learning and pre-primary education as a priority investment area to incentivise government financing for pre-primary education, particularly for marginalised populations, through this new financial instrument.

-

Donors should report accurately to the OECD-CRS database in order to enable tracking of resources to early childhood education.”

The analysis in this report reveals a striking gap between donor promises, policy and practice, a gap that means millions of young children in lower-income countries and other vulnerable contexts are at risk of being left behind. The benefits of pre-primary education for equity in education, for improved learning, for better health and earnings in later life and for returns on investments are undisputed, yet donor governments are failing to support pre-primary education. But commitment at government level and greater investment by donors in pre-primary education today can put countries on track to achieve the vision and ambitions of Sustainable Development Goal 4 by 2030.

Supplementary Data

Please view supplementary data here.

Next resource