“My goal is to integrate science in a fun manner that can make a difference in these children’s lives”

Early childhood development, Global Youth Ambassadors, Right to education, Teachers and learning, Technology and education

A Global Youth Ambassador from Singapore says science is about exploration and discovery - and should be available to any child from any background.

I was waiting at the traffic junction for the green man to flash so that I could cross the road when I overheard (eavesdropped) two schoolgirls having a friendly banter.

They were discussing if boys liked girls with longer or shorter hair, and one of them claimed: “According to science, boys like girls with long hair…”

I am not entirely sure if this is true but what I did notice was the silence and withdrawal of the other girl as if, now that science was brought into the conversation like the “Hidden Immunity Idol” in the reality show Survivor, there was no way of winning the discussion.

This highlighted the bigger issue behind the playful argument. When we hear the word science, what are our immediate thoughts? That is a term loaded with jargons that only “smart” people in specific fields can understand.

To me, science is all about exploration and discovery. My background in scientific research definitely makes me biased towards science – but STEM fields are what will define the future of our countries and economies.

To get the public on board this journey, we need to popularise STEM. I will write particularly about science. How can science be transformed from academic subjects available only to the educated class to a culture where anyone, regardless of background, can relate to and participate in?

How can the phobia of science be broken? It needs to be ensured that scientific ideas are portrayed in a way that is accessible to everyone.

To make scientific concepts relatable and understandable, it has to be “translated” – just like how we appreciate if a foreign language is translated into the language we are familiar with so that we understand the message.

I believe that the fastest way to bring a foreign concept to familiarity is by using analogy but, of course, without diluting the scientific theory or misleading the concepts.

Care needs to be taken to ensure that an attempt to popularise does not take us away from the true meaning of scientific discovery and theory. After all, pseudoscience and science fiction is vastly popular across several generations, though it does not accurately represent the essence of science.

Popularising science is not just essential for adults – it needs to be introduced across age groups including nursery children.

I remember growing up with every opportunity and resource provided for me by my family and school. In school, we had enrichment lessons which supplemented the theories and concepts we learnt during school hours.

We knew that transpiration (or how plants drink water as I remembered it) occurs in plants via their xylem, which transports water from the roots to the leaves. In enrichment class, we got to try it out ourselves – we put celery in coloured water and the next day we were fascinated to see that the leaves became coloured.

We also cut the stalk into half and saw the little coloured dots on the cross section that proved to us that the water was indeed transported from the root to the leaves via a “tube” in the plant.

I also remember my science practical in secondary school. We were learning about the heart – arteries, veins and valves – and our teacher brought the heart of a cow to show us what it looks like in real life. Like a young scientist, I carefully dissected the heart and visualised what we had learnt in our text book.

Popularising science is not just essential for adults - it needs to be introduced across age groups including nursery children Maisha Reza

Experiential learning was what made learning so fun for me. Such learning opportunities, coupled with colourful and engaging YouTube videos and graphics, played an integral part in making the learning of science enjoyable and exciting.

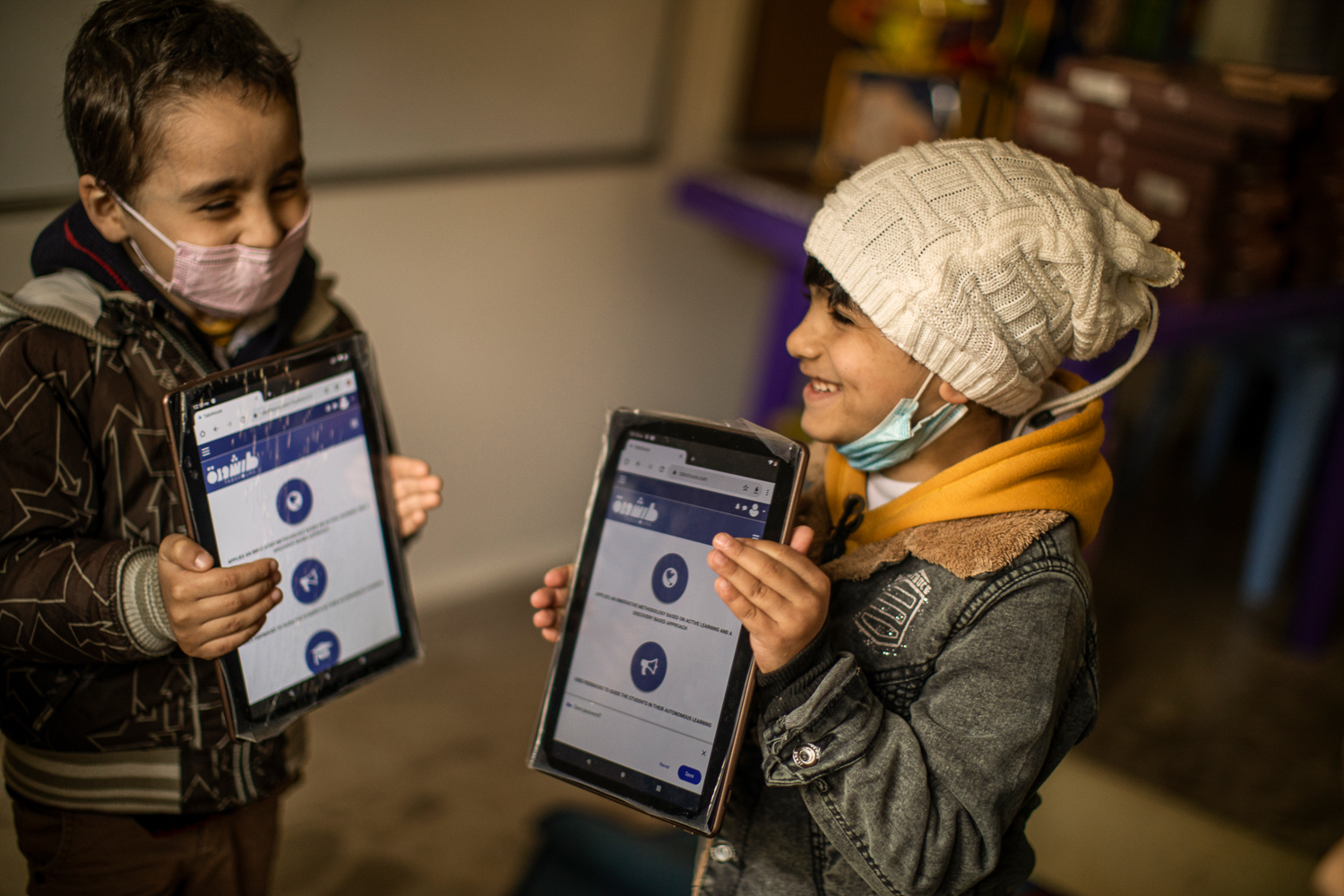

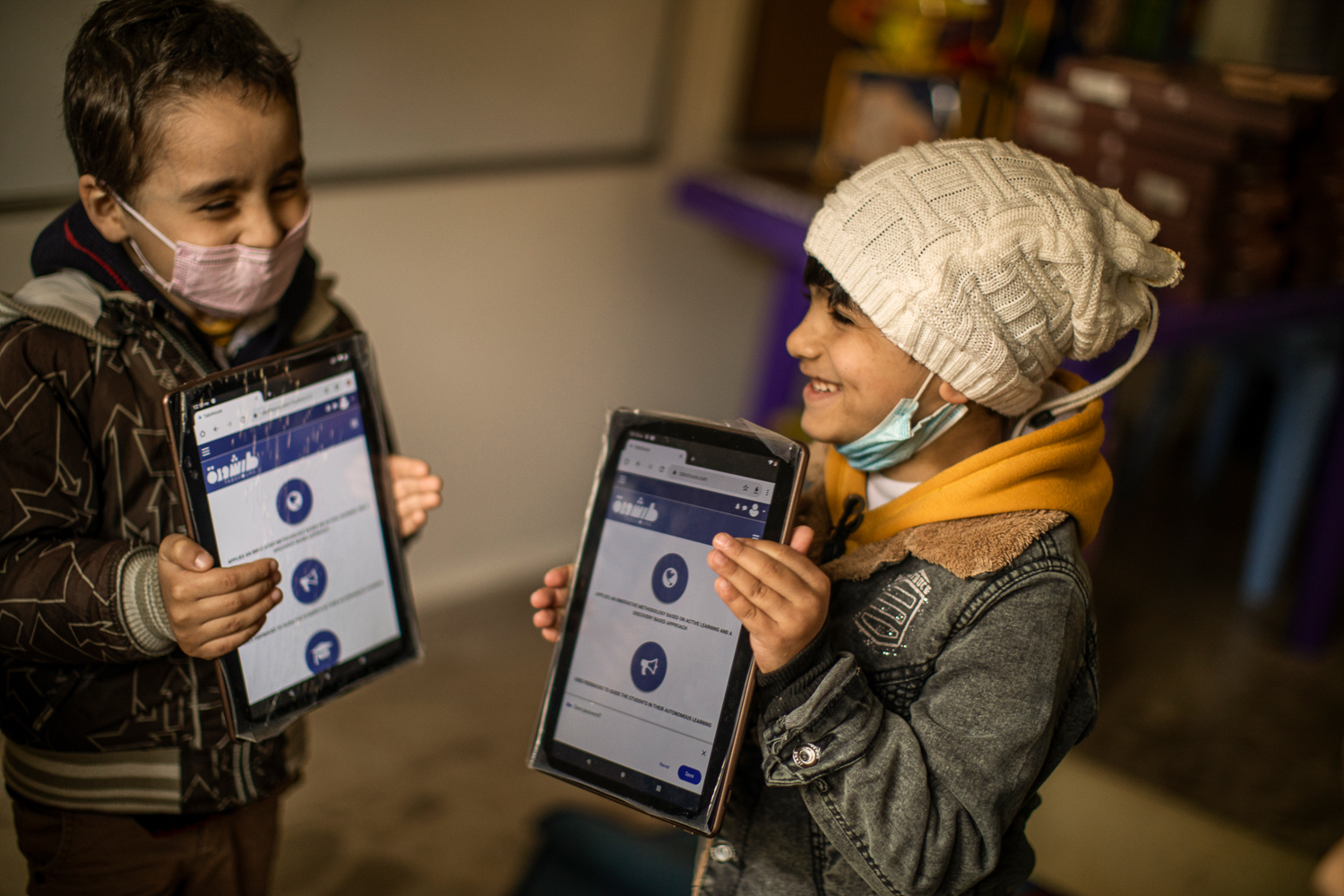

However, not everyone around the world has access to such material and opportunities. In fact, UNICEF reports that 263 million children and youths are out of school and do not have access to quality education.

Children in underprivileged and at-risk environments, such as refugee children, many of whom do not have access to formal education, will also make up the foundation of our social fabric and the backbone of our global future.

From Burkina Faso to Bangladesh, the availability of free schools does not appear to be the problem. Many children who are in school are not learning or performing well either.

Poor motivation and lack of interest are core issues – which is completely understandable. For a child whose family is struggling with poverty and is uncertain of even the near future, what could the purpose of education be then?

Whenever we discuss any issue relating to education, these children are often overlooked. These children, however, cannot be left behind when we discuss about popularising science or even STEM as their participation in essential.

What I do believe we can do is to help make education a little more relatable for them. I am currently developing a creative science programme for underprivileged children. My goal is to integrate science in a fun manner, together with the arts or through activities that can make a difference in these children’s lives.

For instance, it is important to teach young children the value of unity and community building – that only when we cooperate and collaborate with one another can we progress as a community and become successful.

This idea can be reflected elegantly with an electric circuit experiment. Each group needs a paper clip, a small bulb, a wire and a battery. When the circuit is closed – where all items are connected to each other, the bulb will light up.

However, when the switch is open (the paper clip is not touching the side of the bulb), electricity cannot flow through and reach the bulb – hence the bulb will not light up.

Similarly, if there are people in our groups or communities who do not cooperate in maintaining harmony and unity, our “bulb” will not light up.

The concept of electricity and circuits can be a little abstract for children to understand because we cannot see electricity – we have to assume that it flows through the circuit when the bulb finally lights up.

Hence, it would be interesting for the children to do an activity that can exemplify community building while illustrating the theory of electricity flowing.

The children can form a circle and have their hands connected. A hula hoop can then be passed on from one person to the next until it comes back to the first person without anyone breaking the circle or disconnecting their hands.

The children will be the circuit and the hula hoop would be electricity that flows through the circuit. When the hula hoop comes back to the first person successfully, he/she can shout “Hooray!” (to signify the lighting up of the bulb).

How it works: Law of conservation of energy – “Energy can neither be created nor destroyed; rather, it transforms from one form to another.”

For example, the chemical energy that is stored in the battery is transmitted via the wire and the paper clip – which is a metal and a good conductor of electricity – as electrical energy.

Once it reaches the bulb, it is converted to heat and light energy, enabling the bulb to light up. When the circuit is broken, the electrical energy cannot be transmitted.

We can also discuss about materials that are good or poor conductors of electricity. For instance, replace a metal paper clip with a plastic zip tie and, even though the circuit is closed, electricity cannot flow through.

Similarly, if any member of the group refuses to pass on the hula hoop, despite the circle being connected, the hoola hoop cannot reach the starting point.

This shows us that we not only need to be physically present with the members of our community, we need to contribute whole heartedly and be present mentally. It is only with the effort of each individual can we be successful as a community.

This is just one example from the activities that I am developing in hope that science can become an idea that is not just part of academia but can be integrated into our daily lives and conversation.

Science does not only belong to the privileged. I hope that it can be part of a culture that is present in everyone’s lives. Science is everywhere and all around us – whether in understanding how a refrigerator functions or even creating fire by rubbing sticks in the woods.

It is a matter of being aware, understanding and recognising them. Maybe one day, when teachers tell their students to stand in two straight lines, they could say “make a parallel circuit” instead?

More news

African youth rise up to demand early years spending target is met