Natural disasters leave millions homeless and children out of school

Education funding, Education in emergencies, Refugees and internally displaced people

The South Asia floods have put 1.8 million children out of school - but natural disasters are happening all the time and disrupting education around the world.

Natural disasters, such as floods and typhoons, forced 4.5 million people around the world to leave their homes in the first half of 2017 .

They included hundreds of thousands of children whose education has been stopped or disrupted due to schools being severely damaged or destroyed by the extreme weather conditions.

And that was before the impact of last month’s South Asia floods that destroyed or damaged 18,000 schools and left 1.8 million children out of education.

Humanitarian emergencies can stop a child’s education for months or even years – but less than 2% of aid goes towards education in these situations.

Education can be lifesaving in a crisis. Not being in school can leave children at risk of child labour, early marriage, exploitation and recruitment into armed forces.

Save the Children warned last week that the floods in India, Bangladesh and Nepal could leave hundreds of thousands of children out of school for so long that they might never return.

The figures of people uprooted from their homes comes in a new report by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

Between January and June this year, the number displaced by natural disasters almost matched those whose lives were impacted by conflict – an estimated 4.5 million, compared to 4.6 million in war zones.

The most significant disaster in the first half of 2017 was flooding in China’s southern provinces in June, which affected 858,000 people.

The second largest was a tropical cyclone dubbed Mora that hit Bangladesh, Myanmar and India in May and June, affecting 851,000 people.

The rainy season in Peru from January to June impacted 293,00 people and in Sri Lanka 104,000 people suffered after monsoon floods arrived in May and June.

Floods in the Philippines during the first three months of the year affected 381,000 people and Nepal has also suffered terrible flooding – only two years after an earthquake wreaked mass destruction.

IDMC’s report said: “Provisional estimates based on data available show there were over nine million new cases of internal displacement brought on by conflict, violence and disasters between January and June 2017.

“There were 4.5 million new displacements associated with disasters in 76 countries and territories in the first half of 2017 based on figures available.”

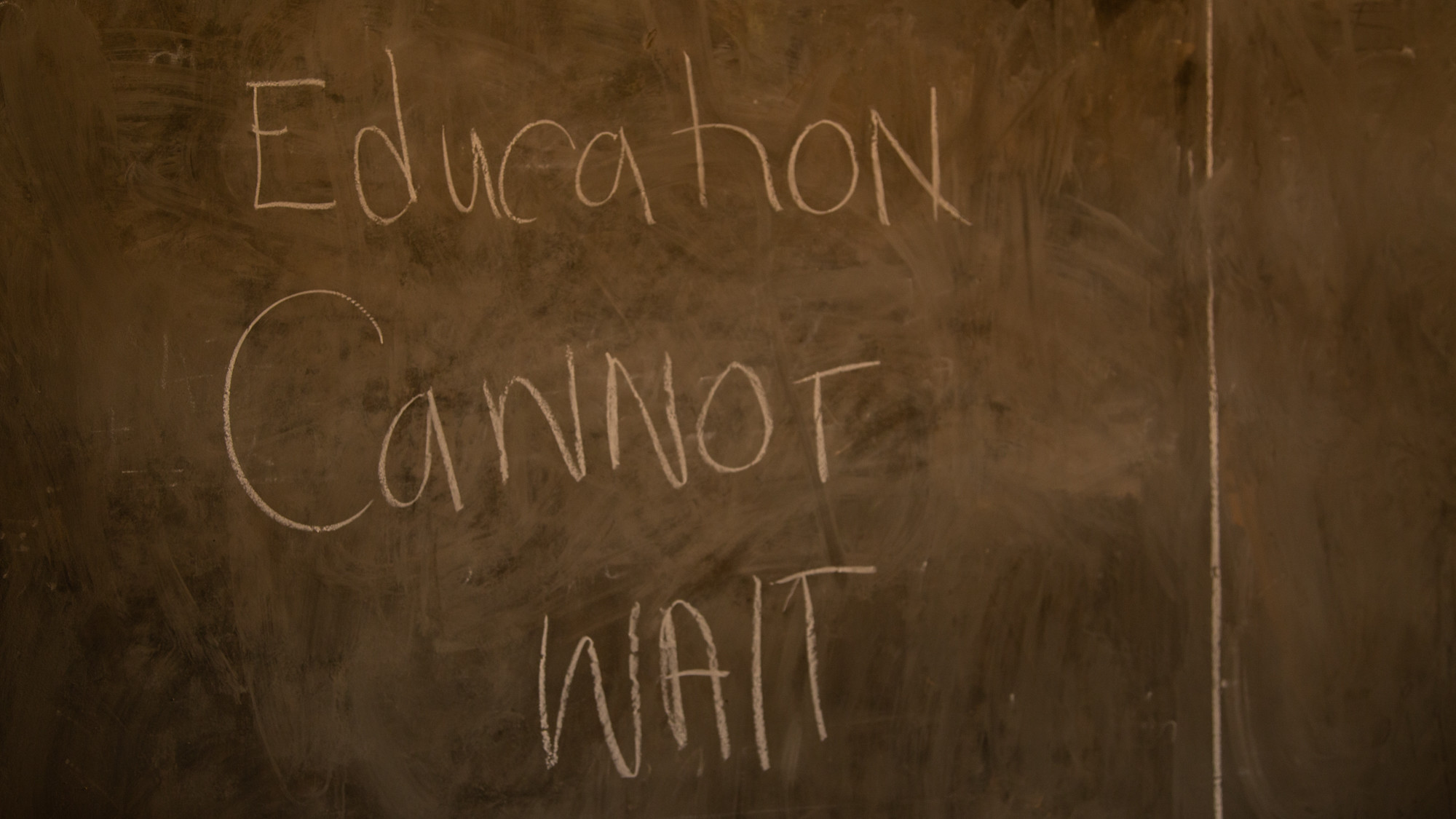

UNESCO said in June that the Education Cannot Wait fund, launched last year, will help to transform the delivery of education in crises.

The fund aims to raise $3.85 billion by 2020 and is already financing education in 10 emergency-affected countries. That includes Peru and Madagascar, both affected by flooding earlier this year.

By providing education in emergencies it’ll be easier for a country to get back on track, because its children and young people are educated. Sigbjorn Ljung, education in emergencies specialist at Plan International

Sigbjorn Ljung, an education in emergencies specialist at Plan International, said education does not receive as much funding as other sectors during natural disasters – because it’s not always viewed as a lifesaving activity in the same way as shelter, food and water.

He added: “In recent years education has been seen as more important though. Various actors are starting to recognise education as being as life saving as other activities.

“It’s easier to understand, for most people, that food, shelter, water and sanitation – how those activities are lifesaving, saving people in emergencies.

“With education you have to think more long term. You have to think about – after a war or natural disaster – how the country has to continue. By providing education in emergencies it’ll be easier for a country to get back on track, because its children and young people are educated.”

Ljung explained that education is also lifesaving in the short term because when children are able to go to school they can “feel a kind of normality and it’ll be easier for them to cope”.

He said: “They will have more psychosocial support at school. Teachers will know how to deal with children who are suffering distress.

“Also children in these settings often don’t see any other options than to go to war themselves. They might be recruited as child soldiers or sex workers or suffer rape. So by providing education in emergency settings children can escape many of these very dangerous routes.”

Plan is currently working in India, Kenya, Sierra Leone and the Lake Chad region, among others. The NGO is also working in Nepal, as is Save The Children.

Sudarshan Shrestha of Save The Children said more than 330,000 houses and approximately 1.7 million people in Nepal have been affected by the recent floods in South Asia. The Humanitarian Country Team has made an emergency response appeal for $58 million.

Shrestha said: “The number of deaths is about 150, of which we understand 23 are children in the 23 districts that have been affected by the monsoon rains and resulting floods.”

The impact on schools has been enormous, according to the Education Cluster, which is headed by the government and co-led by Save the Children and UNICEF. It also includes Plan International, Oxfam, Care and national civil society organisations.

Figures released last week by the UN humanitarian agency OCHA revealed that 30 million people have been affected in India, eight million people in Bangladesh and 1.7 million in Nepal.

The floods damaged or destroyed more than 12,000 schools in India, 4000 in Bangladesh and 2000 in Nepal. Thousands more are being used as shelters for displaced families.

“Millions of children have seen their lives swept away by these devastating floods” said Jean Gough, UNICEF Regional Director for South Asia.

“Children have lost their homes, schools and even friends and loved ones. There is a danger the worst could still be to come as rains continue and flood waters move south.

“Massive damage to school infrastructure and supplies also mean hundreds of thousands of children may miss weeks or months of school.”

Of 2000 schools affected in Nepal, a third have been severely damaged. Around 900,000 children are out of school and most schools affected have lost their teaching materials, classroom furniture, playing equipment and other teaching materials, now beyond use due to flood damage.

Shrestha said that a joint response programme for education is being worked on by the government and the co-leads of the education cluster, to help resume education in the affected areas.

“The cluster team is helping with distributing school kits, early chilhood kits, teaching and learning materials, and repairs for classrooms and school equipment.

“With the festive season called Dasai coming in three weeks’ time, it is unlikely that children will resume with their education until the end of September.”

In Sierra Leone – where mudslides caused an extraordinary amount of damage in August – the charity Street Child has been trying to help affected children.

Education Cannot Wait fund

Tom Dannatt, CEO of Street Child, said schools were being used to house people who had lost their homes.

Speaking at the end of August, he said: “Schools are still out so they are being used as emergency shelters – it would be massively unfortunate if the start of term in September was delayed.

“In Sierra Leone, as elsewhere, evidence clearly shows that the biggest barrier to education is poverty, so when families have lost a large amount then the financial realities of education often take a back seat with families’ priorities.”

Dannatt said the Ebola crisis also severely impacted children’s education with many schools being converted into medical centres during the crisis.

He added: “There was the heartbreaking sight of a lovely school building project that I’d been personally involved in being used…. I was there during Ebola, and remember seeing it handed over to a US initiative… all the furniture had been taken out and was sitting in the open, piled high like a bonfire.

“I remember thinking, ‘I get that you need to use this for the emergency at the moment, but we do need to keep an eye on the future at the same time, and the reality was that this community has not had a junior secondary school before.

“We need to be careful about the future, because who’s to say that money will come to repair all that furniture, which you just rather carelessly tossed to one side.”

More news

Young people’s tireless campaign for an education game-changer