Premature babies study focuses on children’s later learning challenges

On World Prematurity Day, we talk to a mother whose son - born at just 27 weeks - had his developmental needs identified through the world-first Theirworld Edinburgh Birth Cohort.

When Cooper Smith was born 13 weeks early, he weighed a fraction over one kilogram. He stayed in hospital for 89 days, then faced a series of health challenges and was kept permanently on oxygen until he was two and a half.

Now aged seven, he still chokes frequently. But his issues are not only physical.

Cooper’s mother Louise – talking to Theirworld to mark World Prematurity Day today – said medical staff were “so focused on just making sure he was alive, that everything else didn’t matter”. She added: “Yes, he had all the medical needs but he also had developmental needs.”

That was finally identified because Cooper is part of the Theirworld Edinburgh Birth Cohort – a world-first study monitoring the progress of 400 babies from birth to adulthood. The cohort is run by the Jennifer Brown Research Laboratory at the University of Edinburgh, where scans and interactions showed Cooper was experiencing learning and developmental difficulties.

About one in 12 babies born in the United Kingdom is premature. Being born early can affect a baby’s brain development and lead to problems that affect the child throughout life.

Can you help? A donation from you helps this vital research and supports our mission to give every child the best start in life.

Play/span>

Play/span>VideoLouise and Cooper's story

“Prematurity is one of the unsolved problems of modern-day medicine,” said Professor James Boardman, Professor of Neonatal Medicine at the University of Edinburgh, and Scientific Director of the Jennifer Brown Research Laboratory, which Theirworld created 20 years ago.

By monitoring children’s health, development and educational attainment at regular intervals to the age of 25, researchers at the laboratory hope to make discoveries that could help scientists, doctors, parents, policymakers and educators.

The study has made excellent progress in identifying preterm children’s learning and development difficulties in their early years. Now, as the cohort reaches the ages of five and seven and formal schooling is underway, the research is entering a new phase – discovering how the early challenges affect premature children’s learning and what can be done to address it.

Louise, a 37-year-old student midwife from Alloa in Scotland, said she is thankful for the support and advice she receives through the cohort. She added: “It took the Theirworld study to actually get us the recognition that this wasn’t normal, that Cooper has developmental needs.

“I think the impact that being born premature has on these kids is so much bigger than we realise. Without studying it, we’re never going to know.”

Cooper was the third child for Louise and husband Craig. He has a sister Eilidh, 17, and brother Rhuarid, 10. The couple later had another daughter, Ainsley. Tragically, she only lived for two days after being born very prematurely.

Cooper was born at just 27 weeks in the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Louise said: “We thought he might be early because of what had happened in previous pregnancies. He was just absolutely tiny and you could see through his skin.” At one point, she said, Craig noticed that Cooper was “the same width as a can of Coke”.

He was moved to another hospital, where he was treated for a variety of issues including liver failure, infections, jaundice and a heart defect. Then Louise and Craig were told Cooper had chronic lung disease.

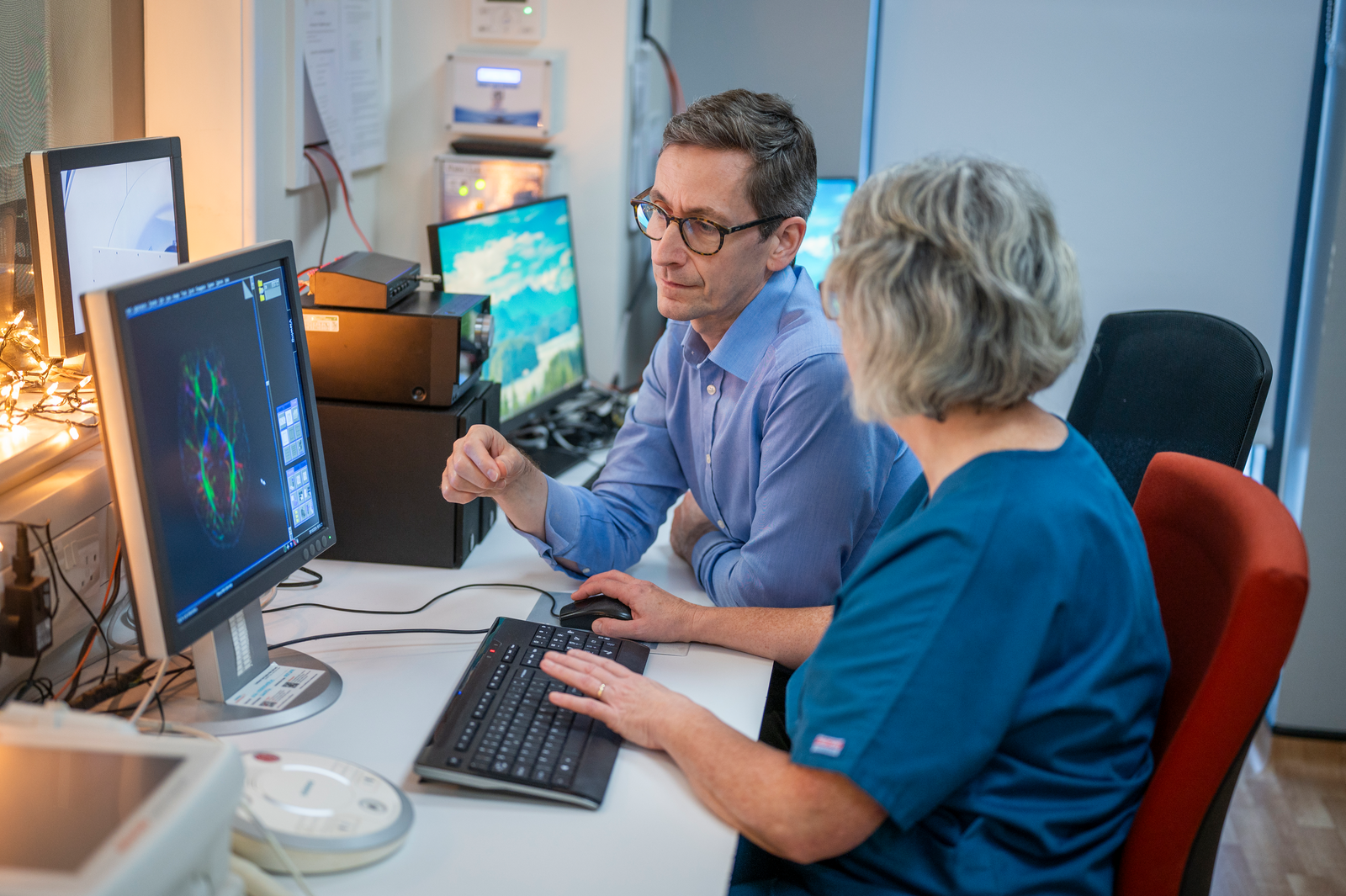

Professor James Boardman looks at MRI images from children in the Theirworld Edinburgh Birth Cohort (Theirworld/Phil Wilkinson)

She said: “It took another two or three weeks before we eventually worked out that this child was coming home on oxygen. And how we were going to deal with that, what that looked like for his future.”

Seven years later, Cooper “still vomits frequently,” said Louise. “He still has very restricted intake. His swallows are now classed as safe but he still chokes on a really regular basis.”

Cooper also has chronic muscular pain, imbalances in muscle tone and joint instability – probably due to brain bleeds shortly after birth. These conditions resemble, but have not been diagnosed as, dyspraxia or cerebral palsy.

He is also waiting for a possible diagnosis of autism. Cooper’s transition to school has been challenging because – although he is highly intelligent – he struggles with the learning environment and is on a waiting list for enhanced support.

Joining the Theirworld Edinburgh Birth Cohort was a turning point for the family. Louise said: “We wanted to know, was his brain developing? Now we’ve got a better understanding of what it involves, what the outcomes of it are. They’re just built differently. They’re wired differently.

“They can’t always pinpoint why but they know that there’s a correlation between tiny prems and these behaviours. That’s been our big feedback, just knowing that he’s not the only one.”

Professor James Boardman said: “We’re seeing children now at the age of five and at the age of seven, which is right on the cusp of starting school. We want to really work out the best way to support a child who’s got difficulties as they transition to this new set of challenges and opportunities in school.

“We plan to do that by working out which cognitive processes, whether that be attention or memory or language difficulties, are underlying the problems with behaviour that some of them experience when they get to school.

“The data that we collect in the Theirworld Edinburgh Birth Cohort is fuelling immense amounts of research here at the University of Edinburgh. But we’re also very keen that the scientific community around the world could use that data.”