One year on: what has happened to the promise to get all Syrian refugee children into school?

Children in conflicts, Double-shift schools, Education funding, Education in emergencies, Refugees and internally displaced people, Right to education, Safe schools

Despite pledges by world leaders, huge numbers of Syrian children are still out of school in neighbouring countries. Theirworld has been trying to get a clear picture of what has happened to the promise to provide quality education for every child during this school year.

Just under a year ago, world leaders met in London and promised to get 1.7 million children – every Syrian refugee child plus vulnerable children in host communities – into school during the 2016-17 academic year.

They declared that children whose families had fled the war to neighbouring countries including Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan would be educated and protected from the risks of child labour, child marriage, exploitation and extremism.

As we approach the first anniversary of the Supporting Syria and the Region conference, hundreds of thousands of refugees are now in classrooms. The host countries, United Nations agencies and NGOs have done remarkably well to integrate so many.

But half – about 800,000 children – are still out of school with only six months to go until the end of the 2016-17 school year.

So what happened to that commitment made in February 2016 to provide a quality education to 1.7 million refugee children and vulnerable children in host communities? Has the $1.4 billion recognised as needed for education been delivered?

And who is making sure that those 800,000 children who have already experienced so much trauma will not be left further behind?

Theirworld has been trying to find out the answers to these and other questions. We contacted each of the co-hosts of the Syria conference – the United Kingdom, Germany, Norway, Kuwait and United Nations – in a bid to get the full picture.

Each of them responded to our requests by supplying details about overall humanitarian aid funding, about specific programmes or projects and how they are helping refugees in general. They referred to reports and updates, including how their own funding is helping children. Their answers covered a range of commitments over a mixture of timeframes.

What we uncovered was the lack of a clear and coherent overview of how that promise to get all refugee children and vulnerable children in the host communities into school in the 2016-17 academic year is progressing.

We even had young supporters – including Theirworld’s network of Global Youth Ambassadors – write to each relevant government asking for the same information.

As a result, we can see that less than a third of the $1.4 billion funding needed for education was committed in 2016. And only about half of the 1.7 million children are in school.

The conference co-hosts are reporting that broad pledges are being delivered and have claimed that the “London Conference is delivering effectively for those who need it. Excellent progress has been made”. But the results on the ground for education show a different story.

Frustratingly, no one government has been able to provide a breakdown of the overall commitment to help those 1.7 million children and there is no data about how much is committed in 2017 or the next academic year. That has to raise questions about the systems of reporting, delivery and accountability.

A senior adviser to the UN children’s agency UNICEF told us that tracking funding is a “complex exercise” and agreed that more transparency was needed to help with planning.

The State Department of the United States, one of the major donors in the region, admitted keeping tabs on funding promised at international conferences was an “imperfect process”.

The Education Commission – a group of world leaders, experts and policymakers – spent a year investigating funding opportunities for education and delivered the Learning Generation report at the United Nations in September.

Its Director Justin van Fleet said: “As the commission highlighted in its report, data and investment in global public goods for education is essential. Lack of accountability on both sides – donor financing and delivery – is a big barrier holding back progress in education.

“When it comes to funding for education in emergencies, I hope that Education Cannot Wait, the new fund for education in emergencies, can make a large contribution by investing in global public goods moving forward to track and monitor education pledges.”

Theirworld’s Director of Campaigns and Communications, Ben Hewitt, said: “The governments of Britain, Norway, Kuwait and Germany have made a commitment to ensure that financial pledges are honoured promptly.

“This requires a free flow of information, a requirement to report, a requirement to regularly show when targets are being met or not met. This is not happening.

“It’s not too late to fulfil the promise made to get all Syrian refugee children into school. We now have six months of the school year left to deliver.”

What happened at the Syria conference?

The Supporting Syria and the Region conference brought together world leaders to discuss how to raise money to help the millions of people affected by the conflict.

It was co-hosted in London on February 4, 2016 by the UK, Germany, Norway, Kuwait and the UN. At the conference, the international community pledged donations of more than $12 billion – $6 billion for 2016 and $6.1 billion for 2017-2020 to allow organisations to plan ahead.

In a statement, the co-hosts said this…

They committed that by the end of the 2016/17 school year, 1.7 million children - all refugee children and vulnerable children in host communities - will be in quality education with equal access for girls and boys. Declaration by co-hosts of the Supporting Syria and the Region conference in February 2016

They said that “funding of at least $1.4 billion a year will need to be met from pledges to the UN appeal and additional bilateral and multilateral commitments”.

What has happened since the conference?

In September – six months after the original promises were made – the co-hosts gave an update at the UN General Assembly in New York.

That event featured a disagreement on stage, with one delegate saying that 80% of the total had been delivered while another claimed the figure was only 43%.

It showed that even officials can be confused by the distinction between various types of funding and its sources.

The then Lebanese education minister Elias Bou Saab told attendees his country was putting refugee children into school without knowing if he was getting the funding to pay for them. He added: “I’m opening schools without having funding for them. We are in a crisis”.

Also in September, Theirworld travelled to the region with Kevin Watkins of the Overseas Development Institute (now CEO of Save The Children UK) and asked key organisations how much funding they had received for education. Our No Lost Generation report found a funding gap of $1 billion on the pledge to get every refugee child in school.

The report said: “Those pledges have not been honoured. The gap between pledge and delivery is hurting Syria’s children.”

It added: “The London Conference is in danger of following a lengthy list of summits that have promised much but delivered little.”

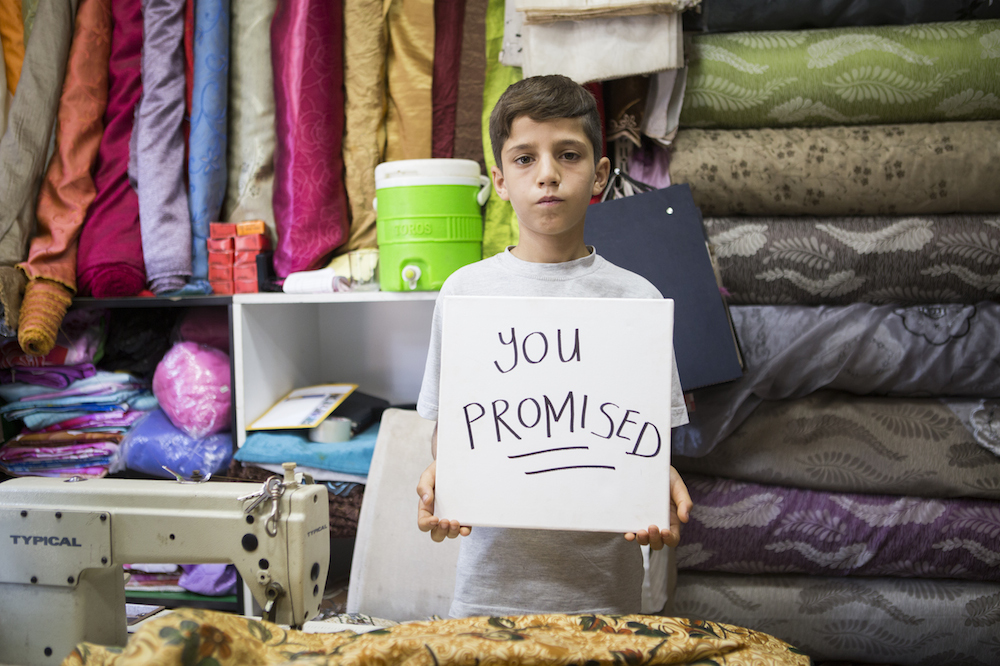

Theirworld launched the #YouPromised campaign to keep up pressure on the donors – reminding them of their pledge to Syrian children.

In November, the Supporting Syria and the Region conference issued a progress report titled “Post-London conference financial tracking”. It said a total of over $10.8 billion in grants and loans had been committed by the 48 conference donors so far.

It did not make much of the pledge to help get children into school, although it did detail some education successes in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. The report listed grants “committed” to education in 2016, which total 27% of the funding needed – but did not say whether these have been delivered.

It also mentioned education funding of 31% but with no further information about where this has been delivered. There is no mention of education funding committed for 2017, making it virtually impossible for anyone reading this report to get a clear picture of the progress.

In fact, the report warned about complacency and pointed out that some donors were still to deliver on their conference pledge, including Kuwait. It asked them to increase their efforts.

The report concluded: “All donors need to be held to account for our promises and delivering at the scale and pace needed. The report published today is a tool to do just that. It finds that donors have delivered almost 80% of pledges made for 2016.”

So what are the co-hosts saying now?

The UK Government’s Department for International Development (DfID) gave details of how British funding is helping in the region and referred us to the conference update report from November. DfID has pledged over £240 million over four years for education. It said new information would be published in February.

The German Embassy in London told Theirworld about its aid for Syrian refugees, including its own commitment to education through various projects and partnerships. Last week, it supplied updated information on its humanitarian aid, including $256 million committed for education. It said its pledge for 2016 had been “contracted in its entirety”.

Norway’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs gave us details of its own specific funding to support education and women affected by the war. It said all its funding for 2016 had been disbursed and that it was increasing funding for education.

It added: “Norway has contributed to ensure that 360,000 Syrian refugee children aged five to 17 have been able to access school in Lebanon and Jordan.”

Kuwait’s embassy in London told us to contact DfID for an update. The co-hosts’ progress report from November showed that Kuwait had disbursed only $11 million out of the $100 million it had pledged.

The United States was not one of the co-hosts but is one of the largest donors helping Syrian refugees. Its embassy in London told Theirworld the US pledged nearly $601 million at the conference – but the State Department said this was not specifically earmarked for education and included funding for both internally displaced Syrians and Syrian refugees. It also gave details of its funding for specific programmes and partnerships.

In an interview with Theirworld, Dina Craissati, a Senior Adviser at UNICEF, told us that during the London conference no specific pledges were made for education.

“The pledges were general so it is not possible to track the current status in relation to the $1.4 billion,” Craissati added.

She said that tracking funding is a “complex exercise” and admitted a more accurate explanation from some nations is needed.

On January 19, UNICEF revealed that almost 500,000 Syrian children are now enrolled in schools in Turkey – a 50% increase in enrollment since last June. But more than 40% of school-age children – about 380,000 – are still missing out.

In or out of school

At the end of 2016, there were 1.6 million registered Syrian refugees of school age in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan.

- TURKEY: 491,896 in school, 380,000 out of school, 871,896 total (ages 6-18)

- LEBANON: 200,000 in school, 277,034 out of school, 477,034 total (ages 3-17)

- JORDAN: 170,000 in school, 91,000 out of school, 261,000 total

UNICEF Deputy Executive Director Justin Forsyth said: “Turkey should be commended for this huge achievement. But unless more resources are provided, there is still a very real risk of a ‘lost generation’ of Syrian children, deprived of the skills they will one day need to rebuild their country.”

On January 20, a coalition of 28 NGOs and organisations issued a report that said almost 200,000 refugee children are now in school in Lebanon – but this is still less than 50% of those registered with the UN refugee agency UNHCR. In Jordan, it said, 91,000 of those registered with UNHCR are still out of school.

In its report – titled Stand and Deliver – the coalition said: “At the London Conference, donors pledged $6 billion for 2016 and a further $6.1 billion for 2017-20. By September 2016, over $6.3 billion had been committed in grants for 2016, exceeding pledges by 5%.”

But it does not specify how much of that has been or will be spent on getting Syrian refugee children into school.

As we approach the first anniversary of the conference, we still do not know if the money pledged at the London conference will prevent the “lost generation” from happening.

The co-hosts’ promise was clear. Section 11 of its declaration stated: “They committed that by the end of the 2016/17 school year, 1.7 million children – all refugee children and vulnerable children in host communities – will be in quality education with equal access for girls and boys.”

The co-hosts need to step up and tell us how that promise will be kept.

What needs to happen now?

Theirworld’s Ben Hewitt said: “The governments of Britain, Norway, Kuwait and Germany made a commitment at the London summit to ensure that financial pledges were honoured promptly so they should now put a motion to the UN demanding people pay up for education. They could also put forward a resolution to European Union colleagues or raise the matter at the World Bank. This would show real leadership.”

We want to get the attention of world leaders, who are currently preparing for the G7 summit in May. You can help by demanding they put children at the top of their agenda when they sit down to discuss the Syrian crisis. We know they listen to this type of pressure – so please send a message. Here’s how you can do that…

More news