Left behind from the start: How governments and donors are failing children with disabilities in their early years (July 2018)

This policy brief highlights the needs of children with disabilities in the early years. It then makes a specific case for the promotion of inclusive and equitable pre-primary education as part of a holistic framework of nurturing care support for children with disabilities.

Jump to

- Introduction

- Discrimination from Day One

- Conflict and emergencies

- The importance of nurturing care

- Early Childhood Education

- Counting children with disabilities

- Spotlight on learning

- The potential of pre-primary education

- Breaking down the barriers

- Why inclusive education benefits everyone

- Designing pre-primary education for children with disabilities

- Recommendations: Promoting inclusivity through early learning

- Acknowledgements

- Bibliography

Introduction

For children with disabilities, exclusion can start at birth and its impact can last a lifetime. Neglect by leaders at every level, negative perceptions and a lack of inclusive policies are all factors that limit children’s participation and deny them the best start in life that every child deserves. The inequality facing young children with disabilities establishes a pattern that persists as they grow up, ensuring they are never given the chance to reach their full potential. A child’s early years are not a time when they should be left behind.

Today, the vital need to support children’s development during these early years is widely recognised; by their fifth birthday, a child’s brain is 90% developed and good nutrition, healthcare, protection, play and early learning at this crucial stage are what set children on the path to the best future possible. Too often, however, this does not apply to children with disabilities whose experience may contrast sharply with the nurturing care and stimulation that are part of inclusive, quality Early Childhood Development (ECD).

For children with disabilities living in developing countries, this nurturing care and stimulation are often missing, as is the education that would enable them to acquire the skills and knowledge that will enable their full participation in society for the rest of their lives, and to which they have a right. As soon as children with disabilities are denied the interventions all children need in those crucial early years, their chances of reaching their full potential start to diminish.

It is during this time that the gaps that exclude children with disabilities first appear, opening divisions that will widen as time goes by. It is not by chance that because of discrimination and lack of access to education and other opportunities, more than 80% of children, youth and people with disabilities are left living in poverty (UN 2015 paragraph 23).

Respecting the rights of children with disabilities as soon as they born and affording them the same freedoms and rights as other children is something that governments are obliged to do, in accordance with the UN Rights of the Child and Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities (CRPD).

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD)

Article 1: Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder the full and active participation in society on an equal basis with others.

Article 3 (h): Respect for the evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities.

If there is to be any chance of achieving the vision of a world where “all human beings can fulfil their potential in dignity and equality”, as set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, children with disabilities need much more support in those early years. To ensure these children reach their full potential, governments and donors must significantly scale up support in the first five years so that all children have the interventions they need.

Of all interventions, the single most impactful one is arguably access to equitable, inclusive quality early childhood education. Support that removes the barriers and gives children with disabilities access to quality ECD, early learning and quality pre-primary education opens the way for children with disabilities for the rest of their lives.

Children with disabilities cannot simply be ignored or treated as a problem in their youngest years. Their lives count, their rights matter and so do their dreams and hopes for the future. This briefing will identify some of the key challenges and recommend measures that governments, donors and international agencies can take to help to solve them

Discrimination from Day One

Each child with a disability is unique. Their disability is just one of many factors that shape their lives. But children with different disabilities often share a common experience: they frequently face stigma that restricts their potential to experience life on an equal basis before it has barely started. The consequences of this stigma are devastating.

There is a clear connection between misconceptions about physical or mental impairment and discrimination and violence against children with disabilities, including infanticide in the most extreme cases (Njelsani et al, 2018). All over the world, violence and mistreatment of children with disabilities is commonplace. One global study found that children with disabilities, including autism, are “particularly vulnerable to bullying as well as emotional and sexual violence” (Know Violence in Childhood 2017 p5). Other research has found that children with disabilities are more vulnerable than others during the first year of life, when all children are most at risk of illness, violence, abuse and neglect (WHO et al 2012).

But stigma and discrimination have other hidden consequences. For children with disabilities in many countries, neglect and social isolation are a common experience. A disproportionate number of children with disabilities are placed in institutional care worldwide (Human Rights Watch 2017). In Serbia, for example, researchers found that 80% of children in institutional care were disabled. In Russia, children with disabilities are often placed in institutions immediately after birth, “where they may be tied to beds, denied health care and adequate nutrition and receive little or no meaningful attention or education” (Ibid). Growing up in an institution can have harmful consequences; UNICEF has said that these include developmental delay, including failure in brain development. These consequences may be so damaging that the UN children’s charity has urged governments to prevent any children under three being sent to live in institutions (UNICEF 2014).

Discrimination puts children with disabilities at a disadvantage from the early years. For girls, this is even more acute, and girls with disabilities are among the most marginalised groups in society all over the world (UNGEI & Leonard Cheshire 2017).

If poverty is also a factor, the challenges are greater still.

Pregnant women who are poor routinely face greater health risks and environmental hazards that can harm the development of the foetus (WHO & UNICEF 2012). One example of this was the outbreak of the Zika virus in Brazil in 2016 that caused many babies to be born with microcephaly – a malformation of the head that affects brain growth and can lead to learning disabilities – and disproportionately affected poor and marginalised women (UNFPA 2016). But poverty also increases risks for babies and young children that can lead to or worsen a disability. In those crucial first five years many poor and marginalised children are at a higher risk of developing a disability because of disease or environmental risks. One of these diseases is polio, which tends to affect children under five and can lead to a lifelong disability. Disease thrives in communities where poor sanitation and hygiene are a daily reality. And stunting and cognitive impairment are a direct consequence of poor nutrition.

But poverty and disability intersect in two ways. The evidence shows that children with disabilities and their families are more likely to experience economic disadvantages, and this doesn’t just happen in developing countries. In 2016 a study found that nearly half of people living in poverty in the UK were disabled or lived in a disabled household and that 310,000 children with disabilities were living in poverty, a higher proportion than their non-disabled peers (Tinson et all, 2016, p 5). The challenges are even greater in low-income countries, where the risk of being poor rises for children with disabilities.

Children with disabilities are often caught in a cycle of poverty and exclusion. Girls become caregivers to their siblings rather than attend school, for example, or the whole family may be stigmatised, leading to their reluctance to report that a child has a disability or take a child out in public. (UNICEF 2013, p29).

Conflict and emergencies

The risk of disability rises in conflict where children may suffer injuries and trauma and healthcare and rehabilitation are inadequate (WHO and World Bank 2011). While reliable data on child casualties of war is virtually non-existent, we know that babies and children under five are not exempt from these risks (Save the Children 2018).

For the youngest children, conflict can cause toxic shock, where development is disrupted by heightened levels of the stress hormone cortisol flooding the brain. This can have profound and lasting impacts including developmental delays and learning disabilities (Theirworld 2016). In the midst of conflict or humanitarian crisis, young children who have disabilities may lose medication or assistive devices, or become separated from family members who protect them from violence or abuse. Here, too, discrimination may be a factor, pushing children with disabilities to the back of the queue for food or services.

How seven years of war in Syria have left children with disabilities at risk of exclusion:

- Children with disabilities are exposed to higher risks of violence and face difficulties in accessing basic services including health and education.

- The risk of violence, exploitation, abuse and neglect for children with disabilities is heightened by the death of or separation from a caregiver.

- Families of children with disabilities in a conflict or crisis often lack the means or ability to provide their children with the assistive equipment they need (UNICEF 2018).

An estimated 10 million people with disabilities have been displaced by conflict, violence and human rights, according to the UN in 2016. To mitigate the risks of physical or cognitive impairment for children with disabilities who have been uprooted by war or crisis, safe spaces and pre-primary education are absolutely vital. Access to quality pre-primary education also enables children with disabilities to get the support that they need.

The scale of the disadvantages facing children with disabilities may seem daunting but governments and donors can develop, implement and strengthen inclusive policies and public services to ensure that all children, including those with disabilities, get the best start in life. Providing equitable access to public services for children with disabilities, including access to learning opportunities in those crucial early years, must become an urgent priority.

Ensuring equity and inclusion from the earliest years is key to building inclusive societies. If world leaders are to hold true to their promise to “leave no one behind”, as in the Sustainable Development Agenda, targeted action is needed from the beginning of a child’s life to achieve disability-inclusive sustainable development.

The importance of nurturing care

All children have the right to nurturing care. For the youngest children, optimal early development requires responsive caregiving, good healthcare, adequate nutrition, security and safety, as well as opportunities for early learning (WHO, UNICEF, WBG 2018). For children with disabilities the stakes are even higher – early detection of disabilities through quality ECD offers the opportunity to identify children who may have undetected developmental delays to get the right support and for their families to access to information they need on the disability (UNICEF 2013). This is especially the case for the poorest families for whom access to any available public service is often limited, bringing multiple disadvantages to the child in question.

The Nurturing Care Framework (WHO, UNICEF, WBG 2018), which focuses primarily on children from birth to age three, refers to conditions in public policy that enable communities and caregivers to ensure children’s good health. This means giving young children opportunities for early learning through interactions that are responsible and emotionally supportive (WHO, UNICEF, WBG 2018 p2). It emphasises that this is not only the right thing to do, it is good for everyone – babies and children, their parents and caregivers, communities, businesses and governments – and stresses that investing in ECD is cost effective (Ibid p1).

Early Childhood Education

The evidence is compelling for the importance of inclusive quality early learning and education in ensuring that all children reach their full potential. Early learning is a built-in mechanism of good quality nurturing care and starts from the very first moments, with simple interactions, observations and play that help children learn and acquire skills. (WHO, UNICEF, WBG 2018). And it includes more structured learning in settings such as nurseries.

Participating in quality pre-primary education “has a significant impact on a child’s future prospects in education and in adult life. it is particularly vital for the most marginalised young children in the poorest countries.” (Rose & Zubairi 2017 p5). This is just as true for children with disabilities, as evidence shows that “investing in programmes that encourage developmental stimulation and responsiveness can improve outcomes for these children”. (Aboud & Yousafzai 2015) particularly in the first 1,000 days of life” (Black & al 2016).

At the same time, there is no one path to learning for children with disabilities, just as there is no single trajectory for other children. For some, learning might progress in the same way as their non-disabled peers and many children with disabilities should have the opportunity for more structured learning in pre-primary education, which is not just essential for their cognitive and social development but is an important step before primary education.

Despite a raft of evidence proving the benefits of early learning and quality pre-primary education, it is something that children from poor and marginalised households are significantly less likely to access (Rose & Zubairi 2017). The children who are missing out on this vital opportunity are estimated to include many millions with disabilities, but the true scale of the problem is not known because of a lack of robust and reliable data.

Counting children with disabilities

This missing data itself presents a huge challenge, as it reduces the ability of children with disabilities to access essential services (Lynch, 2016) and makes them invisible. Research from the Asia-Pacific region has shown that if children are not counted, they may become locked into exclusion. It found that the invisibility and neglect of many children with disabilities meant that developmental delays and disability in young children remain unknown, but “preventative and inclusive ECCE programmes can help mitigate the effect of disabilities and allow children to better integrate into society, to thrive and to become productive individuals” (UNESCO Bangkok, 2018 p xv).

The reasons that children with disabilities are missing out on quality inclusive ECD and pre-primary education are complex. These include discrimination because of their disability, which may be exacerbated by gender. Poverty and conflict also play a major role, as outlined above.

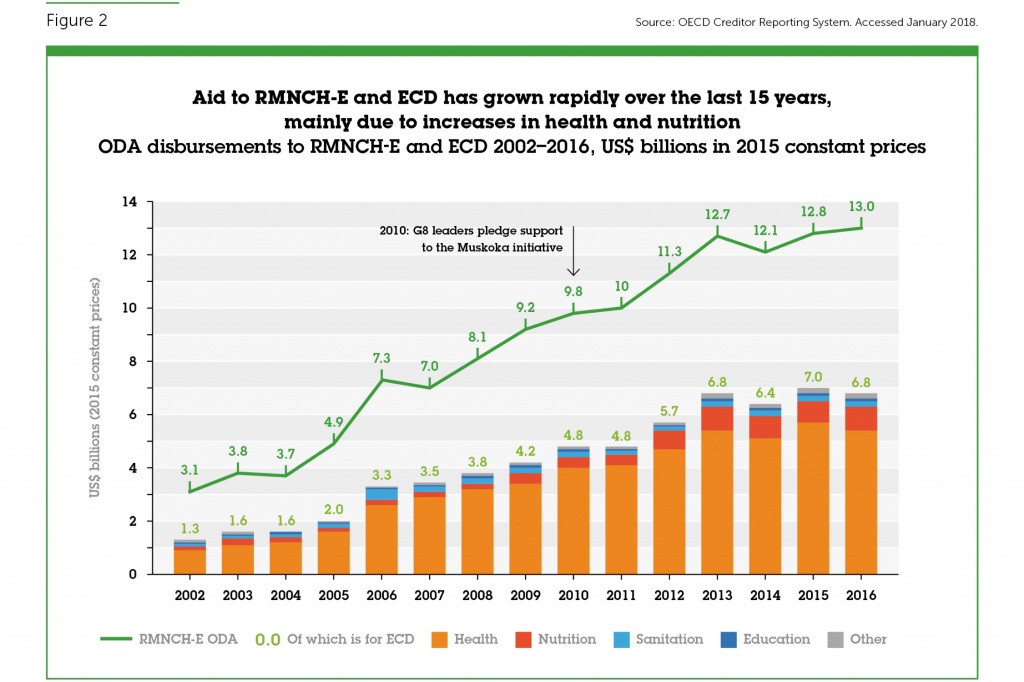

Equally significant, however, is the failure of many governments and donors to prioritise ECD in their budgets and/or to simply disregard key areas of ECD, such as early learning. A recent study on donor support to ECD showed that while investment in ECD has increased in the past decade, that increase has not been holistic across the five key areas necessary for healthy development. It found that while ECD ODA (across all areas) grew from $1.2 to $8 billion between 2002 and 2016, there are huge differences between which of the five key ECD interventions are prioritised by donors. Health and nutrition account for 95% of ECD ODA increases during this period whereas investment in early education declined during those years and accounts for just 1% of total ODA ECD (Rose & Zubairi 2018).

Spotlight on learning

Only a holistic approach to inclusive early childhood development can ensure that children with disabilities are not left behind at the start. This includes early learning as well as good healthcare, adequate nutrition, protection and play. Investment across the board in all of the neglected areas of early childhood development is essential. In the words of the UN CRC: “A mentally or physically disabled child should enjoy a full and decent life in conditions that ensure dignity, promote self-reliance and facilitate the child’s active participation in the community.” There is no better way to help children participate and promote their self-reliance and dignity than by ensuring they get inclusive quality education and learning throughout their lives, starting in the early years.

It’s the responsibility of governments to strengthen policy and commit increased and targeted resources to ensure quality inclusive pre-primary education. The SDG 4 called on governments and their international partners to “ensure that girls and boys have access to quality early childhood development care and pre-primary education” by 2030 (SDG 4, UN, 2016). This target is for all children, including those with disabilities. As we’ve seen earlier, if children with disabilities don’t have equal access to inclusive, quality pre-primary education, they are at risk of a lifetime of disadvantages.

But the global indicators by which progress on SDG 4 is measured currently relies on inadequate data. For example, one of the indicators for target 4.2 on ECD and pre-primary calls for “measurement of the proportion of children developmentally on track”, which will help identify developmental delays and disabilities in young children, the other renders children with disabilities invisible. Indicator 4.2.2 calls for measurement of “participation in organised learning (one year before the official primary entry age)”. But it only asks for disaggregated data by sex and not by disability.

Although those responsible for measuring progress on SDG4 could argue that other indicators (thematic or national) might include data disaggregated by disability, the failure to include this in the global indicator sends a message that counting the participation of children with disabilities in pre-primary is not necessary, which risks their further exclusion.

Governments need to show that children with disabilities count by counting their participation in pre-primary and beyond. Not to do so risks undermining the promise from governments, including donor governments, the World Bank and UN that:

Inclusion and equity in and through education is the cornerstone of a transformative education agenda and we therefore commit to addressing all forms of exclusion and marginalisation, disparities and inequalities in access, participation and learning outcomes. No education target should be considered met unless met by all. We therefore commit to making the necessary changes in education policies and focusing our efforts on the most disadvantaged, especially those with disabilities, to ensure that no one is left behind”. (Incheon Declaration, UNESCO, 2015a).

The missing data masks the shocking extent to which discrimination, exclusion and inequality persist in education, beginning with pre-primary.

The potential of pre-primary education

To achieve SDG4, the best investment governments and donors can make is to provide inclusive quality pre-primary education to support equity and learning from the early years.

The benefits of pre-primary education are well documented, including its potential to mitigate many disadvantages in school and in later life. Pre-primary is key to tackling “the intertwined challenges of the learning crisis and inequality faced by disadvantaged children as they progress through the education system” (Rose & Zubairi 2017).

Evidence from around the world proves that pre-primary education can reduce and even prevent achievement gaps between disadvantaged children and their more advantaged peers, with benefits continuing throughout and beyond education, with an impact on income and reduced inequalities for adults. Children with disabilities must also experience the benefits of quality inclusive pre-primary education that has the potential to protect and enable the “evolving capacities of children with disabilities and respect for the right of children with disabilities to preserve their identities” (CRPD, article 3), as well as to ensure their “full and effective participation and inclusion in society” (ibid).

The number of children with disabilities who may not be able to access these benefits is daunting. UNICEF points out that of “the estimated 100 million children with disabilities under three years of age worldwide, 80% live in developing countries, where the provision of pre-primary education and other basic services tends to be insufficient” (UNICEF 2013 p17).

Again, a lack of data is a factor as children with disabilities are often invisible in household education surveys and so miss out on strategies that target out-of-school children. The number of children who are out of school ranges from at least half (Education Commission 2016) of the at least 65% million children of school age worldwide to 90% (UNICEF 2014b).

In some countries, having a disability can more than double the chance of a child not being in school and in the majority of low and middle income countries, “children with disabilities are more likely to be out of school than any other children”. (GCE & Handicap International). This partly reflects a high school drop-out rate among children with disabilities; it has been estimated that around half of children with disabilities who enrol in primary school drop-out, which would mean that as few as 5% of all children with disabilities all over the world are completing school (UNICEF 2013 p20).

Breaking down the barriers

Disability remains a major barrier to education, despite the CRPD calling on states to ensure that “children with disabilities are not excluded from free and compulsory primary education, or from secondary education, on the basis of disability” (Article 24 (2) CRPD).

Although the experience of accessing education for children with disabilities is different depending on their country, research suggests that across the globe, “disability significantly outweighs other individual and household characteristics” as a barrier in accessing education (Mizunoya et al, 2016). This is especially true for girls with disabilities who face a greater challenge to enrol and succeed in school than boys, leaving them socially isolated and more vulnerable to abuse (IDDC & Light of the World 2016).

Recent analysis of disability data from 49 countries found that in every country children with disabilities were more likely to be out of school than their non-disabled peers (UNESCO Institute of Statistice, UIS 2018). The discrepancy was largest in Cambodia, with a 50-percentage point difference between the out-of-school rate of disabled and non-disabled children (57% versus 7%). But many other countries were also far from achieving disability parity in primary education.

A separate study of 51 countries by the Global Partnership for Education found that in the majority of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asian countries it covered, “fewer than 5% of children with disabilities are enrolled in primary school” (GPE 2016 p vi). Meanwhile, for those in school, a lack of trained teachers, assistive devices or the failure to adapt the curriculum to their needs present significant disadvantages (Ibid).

Gender discrimination can reinforce these barriers. Getting to school may be especially hard for girls with disabilities who have to travel a long way, or whose school lacks accessible toilets, for example. Boys are usually first to be given help with assistive devices or other services, research has found (Leonard Cheshire 2017). Sometimes parents might be reluctant to send their disabled girls to school “because of fears about their safety or in a bid to protect them from sexual violence” (Leonard Cheshire staff quoted by the Thomson Reuters Foundation 2017).

“Imagine not being allowed to attend school or being able to communicate with your parents. This is what happened to Jayita (10), who spent the first five years of her life at home, unable to communicate with her parents, who didn’t think she could learn and didn’t understand her frustration, interpreting this as behavioural difficulties.

“Jayita was five years old when she finally received support from our partner organisation Sama Unnayan Kendra (SUK) in India. Before the support from SUK, Jayita was isolated as she was not enrolled in school. Her paretns were reluctant to give her and education as she was not communicating with them and felt that Jayita had behaviour difficulties.

“Now Jayita is 10 years old and attending school, where her teachers are very supportive, encouraging Jayita to sit at the front of the class and constantly checking with her that she is following the lessons. Jayita dreams of becoming a deaf role model in future to support other children who have been through a similar experience to herself.”

(Deaf Child Worldwide 2018)

The continuing obstacles to education were highlighted in the 2018 World Development Report focusing on education, which noted that participation rates for children were disabilities were significantly lower than for children without disabilities (World Bank 2018).

This discrepancy is in large part a failure of governments and donors to implement implemented targeted policies or direct adequate resources to ensure quality inclusive education for all. Furthermore, seeing disability inclusive education as a burden for education systems that are already stretched ignores the enormous benefits it brings to all.

Why inclusive education benefits everyone

Inclusive education is a fundamental tool to ensure that the universal right to education is achieved for all children and it is a way to reduce the gap in access to education for many children who are currently excluded. But it is also a strategy that is good for everyone. This is not a strategy that is good for children with disabilities only, it is good for all children. Everyone, every child in an inclusive setting will benefit from this. It will include the notion of diversity in our schools and make our classrooms more amenable to our societies, which is what we aim to have. UN Special Rapporteur on the rights of persons with disabilities, Ms Catalina Devandas Aguilar, September 2017

Inclusive education is not only a legal obligation and a human rights imperative, it’s hugely beneficial to children with disabilities and their peers, challenging misconceptions and improving future livelihoods (UNICEF 2013). And when children with disabilities go to school, their families and caregivers have time to rest or to work (Ibid).

But inclusive education also brings wider social and economic returns. Research across 12 developing countries has shown that “each additional year of schooling for people with a disability decreased their possibility of being in the poorest two quintiles by between two and five percentage points” (World Bank 2018 p 63). The returns on investment in education for those with disabilities are two to three times higher than for those without (Lamichhane, K. 2014).

“My daughter studies in an inclusive class and she has made friends with a classmate who has cerebral palsy. Once she was given the task of writing a report on a classmate and she interviewed her friend and described her in the report. I was greatly impressed by the care and affection with which she wrote about her. She simply described her friend, the disability took second place.” Father of Brazilian student with disabilities, (UNESCO 2017a p 88)

All governments – and donors – should make inclusive education a priority in order to build inclusive societies, and all should make sure that children with disabilities have access to inclusive and equitable quality education. This requires removing barriers and taking targeted action to redress the discrimination that blocks access for children with disabilities.

UNESCO says: Reaching children with disabilities before they are of primary school age is therefore vital as holistic quality ECCE programmes can help prepare them for inclusion in state schools. An inclusive ECCE programme must have the adequate specialist support as well as modifications and adaptations to promote child participation (UNESCO Bangkok 2016 p xv).

If governments don’t prioritise inclusive pre-primary education in their education budgets, millions of children with disabilities may never set foot in a classroom. But governments will also need the support of donors who must reverse the systematic underinvestment in pre-primary education (Rose & Zubairi 2016). By scaling up access to inclusive pre-primary governments and donors can lay the foundations for equity in education, enhance learning for all, with social and economic benefits to the individuals, their families and their country.

“Before going to school I didn’t like to get close to people, thinking they were going to make fun of me. But since I started going to school, I feel comfortable. I do everything with my friends. No one rejects me … the future of a child with a disability is at school.” Satta, a 12-year-old girl with a disability from Guinea (Plan International 2016)

Designing pre-primary education for children with disabilities

The disability rights organisation Leonard Cheshire describes inclusive education as “children learning together in the same classroom, using materials appropriate for their various needs and participating in the same lessons and recreation” (Leonard Cheshire Disability p7). According to this definition, children with disabilities should attend mainstream schools that adapt the environment, teaching materials and methods “so that girls and boys with a range of abilities and disabilities – including physical, sensory, intellectual and mobility impairments – can be included in the same class” (Ibid).

The same principles apply to disability inclusive pre-primary, which offers “children with disabilities a vital space in which to ensure optimal development by providing opportunities for child-focused learning, play, participation, peer interaction and the development of friendships” (WHO and UNICEF 2012 p24).

There is no one-size-fits-all model for disability-inclusive education. Each child is unique and pre-primary education needs to be flexible to adapt to different cultures and contexts. As children with disabilities don’t always mirror the same developmental milestones as those without disabilities, they shouldn’t be expected to follow the same rules and curricula (Lynch 2017). What is essential is that “an inclusive ECCE programme must have the adequate specialist support as well as modifications and adaptations to promote child participation” (UNESCO 2016 p xv).

UNICEF guidance on what makes a good pre-school

- A good pre-school programme addresses the whole child and provides holistic development stimulation.

- A good pre-school programme is culturally relevant and respects diversity. It fosters understanding between children.

- A good pre-school programme engages parents and communities.

- A good pre-school programme is inclusive. It fosters children’s rights especially the right to participation.

(UNICEF 2014c, p 10)

For children with disabilities, inclusive pre-primary (pre-school) offers a more informal learning space where they can learn through play and interacting with others in a safe environment where teaching is child-centred. Pre-primary education should be adapted to the needs of the child, including offering guidance and support to enable practical skills for their daily environment (Lynch 2017), as well as specialised teaching. Supporting children at this stage will make sure that they are ready for school when they get there.

Teaching deaf children the basics of Bangla Sign Language before they go to primary school means language and communication development is accelerated, their confidence is boosted and they’re in a stronger position to learn by the time they get to the classroom. All this contributes to children being more likely to go into education and stay in education (GPE blog September 2017).

There are many interventions that ensure education is inclusive, from making facilities accessible to providing assistive devices, to offering more complex support to children across the whole spectrum of disabilities. Teaching and learning materials should be accessible, for example in braille or audio books. At the moment, less than 1% of materials are available in accessible formats for blind or partially sighted readers (International Disability and Development Consortium & Light of the World, 2016).

Children with disabilities also need to have books that show others like them alongside children without disabilities, showing togetherness rather than encouraging divisions. Data on inclusive images and stories in pre-primary books is not readily available, but it has been reported that in primary and beyond just 9% of textbooks show people living with disabilities (UNESCO 2017b).

For teachers, the appropriate training is key. This was made clear by kindergarten teachers in Ghana who said they understood inclusion but lacked the training, materials or support, to create an inclusive classroom. Training teachers and giving them what they need, along with assistive devices, can help build equity and inclusion into education in the earliest years. More teachers with disabilities are needed, to act as role models for children.

Governments must address the global shortage of teachers and equip teachers so they can deliver inclusive education, to meet the obligation in the CRPD: “Governments need to take appropriate measures to employ enough well-trained teachers, including teachers with disabilities, who are qualified in sign language and/or braille, and to train teachers to incorporate disability awareness and the use of appropriate teaching methods” (CRPD article 24).

“At the age of 11 months, Reda, a six-year-old boy from Obeidieh village near Bethlehem in Palestine, had been diagnosed with a large temporo-parietal arachnoid cyst in the left hemisphere. The cyst was removed at the age of 12 months but he was left with very limited vision and had problems moving and sitting, and poor hand function. Since then Reda has been getting support with rehabilitation. He is now able to see big objects, follow movements and recognise people and pictures. Reda has started at an inclusive pre-school after modifications were made to his local kindergarten to support his involvement. The kindergarten was equipped with suitable and age-appropriate teaching and learning materials and toys. The pre-school director, teachers and other staff, as well as the students and their families were prepared for welcoming Reda, and the teachers were provided with relevant training and teaching techniques that would enable them to meet the specific learning needs of young children with impaired vision. Adaptations to the pre-school curriculum and teaching methods were also made. Reda is now able to walk and use his functional vision in an appropriate way that helps him benefit from his residual vision. He was very sociable and was well accepted and liked by his peers and teachers at the kindergarten and was able to acquire the basic readiness skills. He is now looking forward to joining his peers when they move up to primary school.”

(GCE and Handicap International 2013, p29)

Unfortunately, positive early educational experiences like the one described above are rare for children with disabilities. If they cannot access inclusive quality pre-primary education, children with disabilities are left behind before their lives have barely started. As UNICEF notes: “Education is the gateway to full participation in society. It is particularly important for children with disabilities who are often excluded” (UNICEF 2013 p27).

This exclusion sets in motion a pattern of inequality that will restrict their chance of reaching their full potential. Attitudes are shifting but negative perceptions, family shame and neglect by leaders at every level are still limiting the participation and opportunities of children with disabilities.

As we have seen, the challenges are enormous but governments can initiate changes now that will lead to significant achievements by 2030. This will require targeted action by governments to expand on disability-inclusive pre-primary education, including additional resources. The following recommendations propose the steps that should be taken so that more and improved resources can be made available to meet the financing needs to ensure universal access to pre-primary education by 2030, including the public financing for two years in pre-primary education in all countries.

Recommendations: Promoting inclusivity through early learning

National governments

- Increase the overall share of national resources and begin redirecting education budgets to ensure two years of pre-primary with funding in place by 2020 to allocate at least half of the education budget to this sector.

- Review and update national education policy in line with commitments to provide free pre-primary to all children, ensuring progressive universalism, with a specific focus on targeting children with disabilities.

- Increase the number of teachers with specialist training in inclusive education, making sure that that teachers with disabilities are represented.

- Review the curriculum and teaching and learning resources for young children to support inclusive education, making sure materials suit the needs of those with disabilities.

- Generate robust data and evidence for inclusive planning, programming and for ensuring accountability.

- Ensure data collection for SDG4 2.2 is disaggregated to capture the participation of children with disabilities.

- Enable information sharing, advice and support for parents and communities to promote the inclusion of children with disabilities in school and wider community.

- Ensure that children and young people with disabilities, their families and disabled people’s organisations, with development actors, further the inclusive education agenda.

- Engage actors from health sector and other sectors to ensure that early learning interventions benefit from and include a holistic approach to design, delivery and equitable finance

Bilateral and multilateral donors

- ODA resources to pre-primary education should increase in volume and be sufficiently targeted to benefit the poorest and those with disabilities, with at least 10% of all education ODA to targeted at pre-primary, including in humanitarian crises.

- The World Bank should allocate at least 10% of its education budget to pre-primary and prioritise support for low-income countries, as well as support children with disabilities.

- The Global Partnership for Education should increase allocations to pre-primary to at least 10% of its budget and ensure support for children with disabilities.

- International donors should support the establishment of the International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd) to increase overall resources for education globally. The IFFEd must support countries to mobilise, front-load and better target resources for pre-primary education, including support for children with disabilities.

- All humanitarian response plans should include targets that address the needs of children aged 0-5 in a holistic way. Education Cannot Wait, the new fund of education in emergencies, should prioritise pre-primary education and early cognitive support as part of initial emergency investments and long-term strategy, with targeted measures to support children with disabilities.

- Involve people with disabilities, their families and disabled people’s organisation, in partnership with development actors, to further the inclusive education agenda.

- Engage with financing and programming from the health sector and other sectors to ensure that early learning interventions benefit from and include a holistic approach to design, delivery and equitable finance

UNESCO and other international agencies

- Call for and strengthen support for countries to collect data for SDG4 2.2; ensure data is disaggregated to capture the participation of children with disabilities.

Acknowledgements

This brief was prepared for Theirworld in July 2018 by:

Writer/Editor: Jo Griffin

Lead researcher and contributing author: Kate Moriarty

With additional contributions by:

Justin van Fleet

Ben Hewitt

Stephanie Parker

Bibliography

Clarke, J. (2017). A global campaign for disabled children’s education. Global Partnership for Education https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/global-campaign-disabled-childrens-education

Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) (2006) https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities.html

Deaf Child WorldWide (2018). ‘Imagine not being allowed to attend school’ http://www.deafchildworldwide.info/news_events/imagine_not_being.htm

Education Commission. (2017). A Proposal to Create the International Finance Facility for Education. International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity.

Gladstone, M. McLinden, M, Douglas, G Jolley,E. Schmidt,E. Chimoyo,J.Magombo H. and Lynch P. (2017). ‘Maybe I will give some help…. maybe not to help the eyes but different help’: an analysis of care and support of children with visual impairment in community settings in Malawi’ . Child: Care, Health and Development Published by John Wiley & Sons Ltd

Global Campaign for Education and Handicap international (2014). ‘Equal Rights , Equal opportunity: Inclusive Education For Children With Disabilities’. GCE, South Africa. http://www.campaignforeducation.org/docs/reports/Equal%20Right,%20Equal%20Opportunity_WEB.pdf

Global Partnership for Education Secretariat. (2016). ‘Children with disabilities face the longest road to education’. GPE, Washingtone DC https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/children-disabilities-face-longest-road-education

Global Partnership for Education (2017). ‘A global campaign for disabled children’s education.’. GPE Blog. https://www.globalpartnership.org/blog/global-campaign-disabled-childrens-education

Global Partnership for Education. (2018). ‘Disability and Inclusive Education A Stocktake of Education Sector Plans and GPE-Funded Grants. Working paper #3’ February 2018. Global Partnership for Education. Washington DC.

Human Rights Watch. (2017). Children with disabilities: Deprivation of liberty in the name of care and treatment. HRW, New York. https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/03/07/children-disabilities-deprivation-liberty-name-care-and-treatment

International Disability Alliance. (2017). ‘Side event to the 36th Session of the Human Rights Council: “Empowering Children with Disabilities through Inclusive Education: Building on Diversity”.’ Web report International Disability Alliance. http://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/SE_HRC36_InclEdu

International Disability and Development Consortium & Light of the World. (2016). ‘#CostingEquity The case for disability-responsive education financing’. UK. https://iddcconsortium.net/sites/default/files/resources-tools/files/iddc-report-short_16-10-17.pdf

Know Violence in Childhood ( 2017) Know violence in Childhood. (2017). ‘Global Report 2017: Ending Violence in Childhood’ https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/node/12380/pdf/global_report_2017_ending_violence_in_childhood.pdf

Lamichhane, K. (2014) Disability, Education and Employment in Developing Countries: From Charity to Investment. Cambridge University Press.

Leonard Cheshire Disability. (2013). Inclusive Education: An Introduction https://www.leonardcheshire.org/sites/default/files/LCD_InclusiveEd_012713interactive.pdf

Lynch, P. (2016). “Early childhood development (ECD) and children with disabilities” http://www.heart-resources.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Paul-Lynch-reading-pack-1.pdf

Lynch, P. (2017). ‘Blog: Disability and school-readiness in rural Malawi’. The Imoact Initiative. UK. http://www.theimpactinitiative.net/blog/blog-disability-and-school-readiness-rural-malawi

Mizunoya,S., Mitra, S., Yamasaki, I. (2016) ‘Towards Inclusive Education The impact of disability on school attendance in developing countries’. UNICEF Innocenti

Njelesani J, Hashemi G, Cameron C, Cameron D, Richard D, Parnes P. (2018) ‘From the day they are born: a qualitative study exploring violence against children with disabilities in West Africa’ BMC Public Health. 2018; 18: 153. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5773174/#

Plan International (2016). “Satta: My Disability Won’t Hold Me Back” https://plan-international.org/guinea/satta-my-disability-wont-hold-me-back

Rehbichler, S., and Baboo, N. (2017). ‘Investment in Disability inclusive education: Delivering on the commitment to leave noone behind guided by Art.24 of the UNCRPD’. International Disability and Development Consortium & Light of the World. UK

Rose, P., and Zubairi, A. (2017). ‘Bright and Early: How financing pre-primary education gives every child a fair start in life’. Theirworld. UK

Rose, P., and Zubairi, A. (2018). Donor Scorecard Just Beginning: Addressing inequality in donor funding for Early Childhood Development. Theirworld. UK

Save the Children International (2018). ‘The war on Children: Time to end grave violations against children in conflict’. Save the Children. UK.

Tinson, A., Aldridge,A., Born, T., and Hughes, C (2016) ‘Disability and poverty Why disability must be at the centre of poverty reduction’ New Policy Institute supported by Joseph Rowntree Foundation

UN (2015). ‘Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’. United Nations. New York.

UN (2016). ‘One humanity: shared responsibility: Report of the Secretary-General for the World Humanitarian’. UN. Summit http://undocs.org/A/70/709

UNESCO (2015a) ‘Incheon Declaration’ UNESCO, Paris. http://webarchive.unesco.org/20160930040522/https://en.unesco.org/world-education-forum-2015/incheon-declaration

UNESCO (2015b) ‘A Review of the Literature: Early Childhood Care and Education (ECCE) Personnel in Low- and Middle-Income Countries’ http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002349/234988E.pdf

UNESCO (2016) ‘New Horizons: A Review of Early Childhood Care and Education in Asia and the Pacific’. UNESCO Bangkok Office

UNESCO (2017a). ‘School for all’ (Original title: Escola para todos: experiências de redes municipais na inclusão de alunos com deficiência, TEA, TGD e altas habilidades. Published in 2016 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and UNESCO in Brazil in partnership with Mais Diferenças. ). UNESCO Brazil.

UNESCO (2017b). Having a disability shouldn’t affect your access to education. UNESCO Global Education Monitoring Report. Paris. https://gemreportunesco.wordpress.com/2017/12/01/having-a-disability-shouldnt-affect-your-access-to-education/

UNFPA. (2016). ‘Poverty, inequality at the heart of the Zika outbreak. ‘https://www.unfpa.org/news/poverty-inequality-heart-zika-outbreak

UNGEI and Leonard Cheshire (2017) ‘Still Left Behind — Pathways to Inclusive Education for Girls with Disabilities’ https://www.leonardcheshire.org/support-and-information/latest-news/press-releases/still-left-behind-pathways-inclusive-education

UNICEF (2013) Children and Young People with Disabilities Fact Sheet May 2013 https://www.unicef.org/disabilities/files/Factsheet_A5__Web_NEW.pdf

UNICEF. (2014a). “A Brighter Future for All: For every child to grow up in a caring, supportive family”. Press Centre (9/2014) http://unicef.org.tr/basinmerkezidetay.aspx?id=12485&dil=en&d=1

UNICEF. (2014b). Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children: SOUTH ASIA REGIONAL STUDY Covering Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Sri Lanka https://www.unicef.org/education/files/SouthAsia_OOSCI_Study__Executive_Summary_26Jan_14Final.pdf

UNICEF (2014c). ‘Inclusive Pre-School Programmes, Webinar 9 – Companion Technical Booklet’. UNICEF. New York https://www.unicef.org/tfyrmacedonia/9._inclusive_pre-school.pdf

UNICEF (2018). ‘No end in sight to seven years of war in Syria: children with disabilities at risk of exclusion”. https://www.unicef.org.uk/press-releases/no-end-sight-seven-years-war-syria-children-disabilities-risk-exclusion/

World Bank (2018). World Development Report 2018; Learning to realise education’s promise’. World Bank Washington DC. http://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018

WHO and World Bank (2011). ‘World Report on Disability’ http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/en/

World Health Organization & UNICEF. (2012). Early childhood development and disability: a discussion paper. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75355

WHO, UNICEF, WBG (2018). ‘Nurturing care for Early Childhood Development: A framework for helping children survive and thrive to transform health and human potential. WHO. Switzerland. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272603/9789241514064-eng.pdf?ua=1

Next resource