Education aid is falling and failing to reach the right countries warns UNESCO

Barriers to education, Education funding, Education in emergencies, Refugees and internally displaced people, Right to education, Teachers and learning

Donors are shifting their attention away from the poorest countries, says a new report that reveals aid for education decreased for six years in a row.

Education’s share of aid has been decreasing for years – and is not being targeted at the countries that need it most.

That means aid is falling well short of what is needed if every child around the world is to get into school, the United Nations revealed today.

“Aid would need to be multiplied by at least six to achieve our common education goals and must go to countries most in need,” said Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO.

“Yet we see that donors to education are shifting their attention away from the poorest countries.”

That’s depressing news for the 263 million children and adolescents who are out of school globally. The Sustainable Development Goals agreed by world leaders include a target of getting every child a quality primary and secondary education by 2030.

However, the amount of aid allocated to education has been falling for six years in a row, according to a policy paper published by UNESCO’s Global Education Monitoring (GEM) Report.

While overall development aid increased by 24% from 2010 to 2015, the amount spent on education dropped by 4%. It is now less than the funding for transport.

Campaigners say the G20 summit in July will be crucial for the future of education funding.

The global Education Commission, a group of world leaders and experts, says spending on global education will have to almost treble for the 2030 target to be achieved.

Justin van Fleet, the commission’s director, said: “One of the things we’re asking donor countries to think about doing is to prioritise education to the same level as health, to make education 15% of their overseas development assistance and to channel more of that money towards multilateral funds.”

The UNESCO paper reported that aid to education in 2015 was $12 billion – with $5.2 billion going to basic education, which includes pre-primary and primary schooling. Aid to secondary education was $2.2 billion.

To compound the problem, the aid that is being allocated to education is not going to the right places – low-income countries with the highest out-of-school rates.

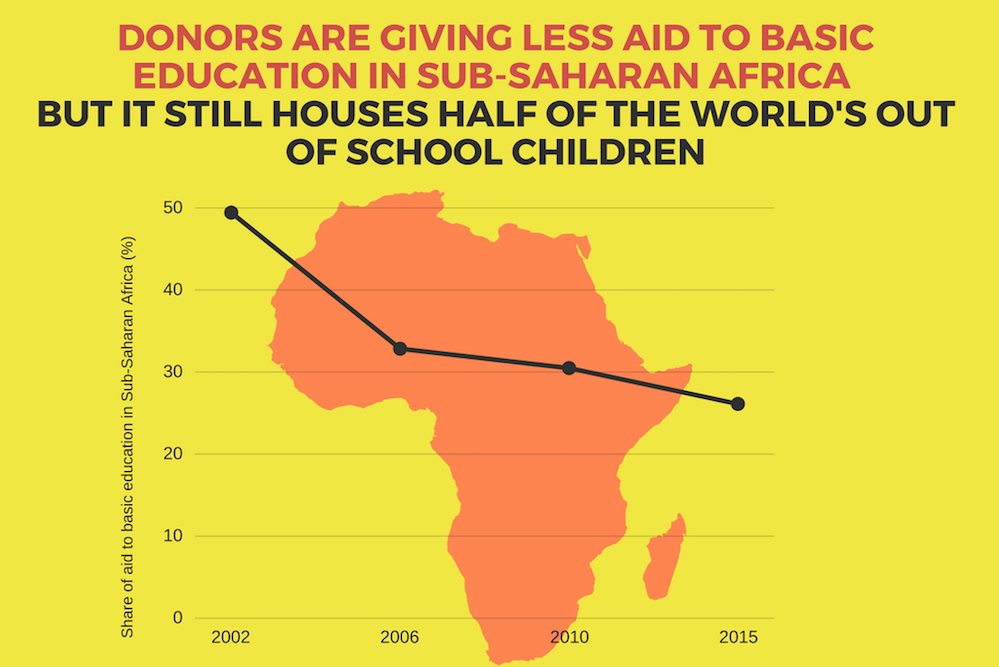

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to more than half of the world’s out-of-school children – but gets less than half the aid to basic education it received in 2002.

It receives 26% of the total current aid to basic education – barely more than the 22% allocated to Northern Africa and Western Asia, where 9% of children are out of school.

There has been some success on increasing aid for education in emergencies, including conflicts and natural disasters.

Humanitarian aid to education has reached a historic high, increasing by 55% from 2015 to 2016. But it still receives only 2.7% of total aid – and less than half of the amount requested.

UNESCO said the Education Cannot Wait fund, launched last year, will help to transform the delivery of education in crises. The fund aims to raise $3.85 billion by 2020 and is already financing education in 10 emergency-affected countries.

The policy paper mentions two other major proposals for to reverse the fortunes of education funding.

A replenishment campaign by the Global Partnership for Education is seeking to raise $3.1 billion for 2018-20 and $2 billion annually by 2020. That is four times the current funding level.

UNESCO said: “In contrast to trends in bilateral aid to education, the GPE allocated 77% of its disbursements to sub-Saharan Africa and 60% to countries affected by instability and conflict.”

The other proposal is an International Finance Facility for Education (IFFEd), put forward by the Education Commission, which says it could leverage around $10 billion in additional financing per year by 2020.

This would allow development banks to expand their education funding and target lower middle-income countries.

More news