“Learning to read in their mother tongue helps to accelerate children’s learning”

Barriers to education, Teachers and learning

A new programme is teaching young children in Mozambique to read in their native language before moving on to learn Portuguese.

Young children in Mozambique speak in one of several native languages when they enter school.

But they frequently are taught to read in Portuguese, the official language of the nation. This can be an obstacle when it comes to them acquiring early reading skills.

To help improvements in early reading, Planet Aid and its partners ADPP Mozambique and Cambridge Education have been implementing an early-grade reading programme that teaches children to “crack the code” of the written word by learning to read in their mother tongue.

This helps to accelerate learning and makes it easier for children to later learn Portuguese. The project has developed classroom and other materials for early-grade reading in two national languages – Xichangana and Xirhonga. It has also developed and is implementing teacher and reading-coach training programmes.

The literacy initiative is part of Planet Aid’s Food for Knowledge project, which is funded by the US Department of Agriculture under the McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program.

Paula Green, Ph.D., is a literacy specialist with Cambridge Education working on the literacy component of Food for Knowledge. She has extensive experience of developing early-grade reading programmes and was a senior literacy specialist and national training manager for 16 years with the prestigious Molteno Institute for Language and Learning in South Africa.

We spoke with Dr Green in South Africa to discuss the work being done in Mozambique to strengthen literacy.

Why is a focus on literacy important for Mozambique?

We often say that the first three years are when children “learn to read” in order that in later years they can “read to learn.” Through literacy, children gain access to the knowledge and skills available in all other subjects. Without this foundational skill, the years spent in school are at best demoralising, at worst useless.

The Mozambique Ministry of Education and Human Development has been concerned about alarming statistics on student learning outcomes and has made early-grade reading a national priority. Although progress has been made, the government is still in the process of rolling out its bilingual education initiative.

The Food for Knowledge literacy component is aiding the bilingual education strategy of the ministry. From the very outset and on an ongoing basis, the literacy team has worked diligently with the ministry to develop and implement this programme.

What is the approach and the evidence behind it?

The National Reading Panel in the United States is a key part of the empirical foundation of the project, as it is for most current literacy interventions in the developing world.[1] Based on a wide-ranging meta-study, the panel identified a combination of effective elements involved in teaching early-grade reading.

These elements are the concepts of print, phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension.

Our approach relies on a systematic, daily practice of skills that support a child’s ability to read and write independently. It adheres to a Gradual Release of Responsibility methodology, encouraging teachers to model and practise with the children and then to support them in practising by themselves.

Instruction begins using the children’s locally-spoken language and gradually introduces Portuguese into the curriculum.

Because the content and methodology are new to most teachers in Mozambique, the approach employs strong scaffolding, especially during the introductory phase.

Scaffolding means to provide detailed lesson plans that clarify each step of the instructional sequence, helping to build skills in the new methodology.

As the teachers become more confident with the activities and steps, they can choose to adapt or generate their own lesson plans to suit the particular needs of their own learners.

What has the project done so far?

Our first task was to develop a framework for the systematic development of listening, speaking and letter knowledge, along with comprehension and writing skills for the first grade.

Close collaboration with the Ministry of Education on this ensured that the programme aligned with the official curriculum.

We then focused on developing weekly lesson plans for grade one along with a wide array of instructional materials that include a three-volume teaching guide, 28 read-aloud stories, 22 decodable books, student books, conversation posters and more.

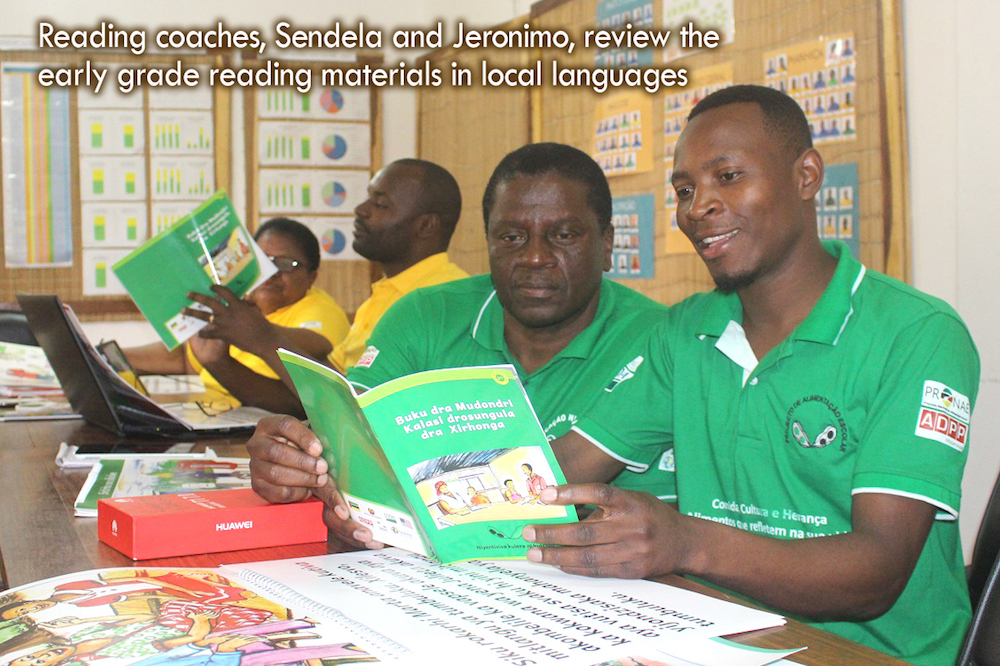

Next we developed a training plan and manuals for teachers and literacy coaches and completed all the training. There are currently 27 coaches that are providing support to 215 teachers at 141 schools.

Part of the coaches’ training involved the use of electronic tablets for recording classroom observations and for administering a shortened version of an assessment called the Early Grade Reading Assessment (EGRA) weekly. The results are then transmitted in real time to headquarters staff, who monitor results and provide feedback.

How else is the literacy component being monitored and evaluated?

The literacy component will undergo a complete external evaluation by outside experts, using the full EGRA methodology. The baseline analysis for the evaluation was recently completed and the final evaluation will be performed in three years.

But that’s not all. We wanted more frequent performance monitoring to better inform our practice as we go along. So we also developed a baseline literacy test in Xichangana and Xirhonga (as well as Portuguese) and administered it in grades one to three in May.

The findings of this baseline are being used to inform the development of the second and third-grade materials. There will also be an internally-conducted end-line study.

Teachers are also encouraged to carry out weekly assessments of students and record their scores. These teacher-performed assessments are designed to be easy to do so as not to overwhelm teachers and run the risk of them avoiding assessment altogether.

What is your outlook for the future of the project?

I feel very positive and excited about the possibility of making a lasting impact. I say that having had many years of experience in many other literacy programmes in sub-Saharan Africa.

I am pleased that the materials are being well received and am proud that, in a very short time, we have managed to develop a large quantity of materials to an acceptably high standard.

Also, the fact that this programme has employed dedicated reading coaches is a strength. The ongoing support they are providing the teachers addresses one of the common challenges of such programmes, where the enthusiasm generated during training dissipates when teachers get back to school and are faced with the challenges of large classes, limited resources etc.

The fact that the teachers are visited regularly by enthusiastic, supportive coaches will go a long way to sustain commitment, hopefully well beyond the years of the programme.

Another factor that bodes well for sustainability is the commitment of the literacy team and support provided by the senior team. Effective working relationships take time to be established.

This has been the case in our team – getting processes established, recruiting the additional essential staff and allocating roles to specific team members.

We are about to embark on a big programme of second-grade materials development, while still supporting the existing first-grade classes. Though the extent of the work is daunting, I am encouraged that we are on the right track. We know where we are going and what we want to achieve.

[1] Other key sources of empirical evidence are taken from the growing body of research advocating for and proving impact of mother-tongue based bilingual education (such as Alidou et al., 2006 and UNESCO, 2008).

More news

Take the test and discover how our Schools Hub helps students grasp the global education crisis